Reality: The world or the state of things as they actually exist, as opposed to an idealistic or notional idea of them: “he refuses to face reality”. – Webster’s English Dictionary definition

In 1921, Ludwig Wittgenstein published his most significant philosophical writing Tractus Logico-Philosophicus. In his book, Wittgenstein does not argue on behalf of his beliefs as they pertain to reality, but instead presents his reader with a number of observations whose validity he believed to be self-evident. The sum of Wittgenstein’s observations present the reader with a perspective of our shared reality that is designed to undermine the conventions and the stability with which man kind has always employed when grappling with the world around him. In summation, Tractus Logico-Philosophicus presents a reality without any definite truth, where knowledge as we know it is nothing more than a human invention. The components of this “human invention” consist of numerical labels and names that allow the human intellect to reason with his/her surroundings, to navigate a reality as subjective as it is believed to be objective.

Wittgenstein’s work has become one of the most influential philosophical studies of the twentieth century, and is, along with the works of Henri Bergson, essential to the development of film theory and criticism. Consider that everything contained within a frame and the accompanying soundtrack of a film is a “reality”. To navigate this reality, the filmmaker has broken it up into various shots. These shots, aligned during the film’s post-production, allow a fluidity of experience, simulating the human experience of time or life. The denominations of a film’s parts (shots, sequences, scenes, acts) are therefore synonymous with the numerical labels Wittgenstein attributes to man’s invention of a “shared reality”.

The parts of the film, assembled by the filmmaker, each represent a distinctly emotive signifier that the audience utilizes to navigate the film’s narrative. Each member of the audience, with his or her own subjective perspective, will interpret these signifiers differently, though without much variation. This phenomenon speaks directly to Wittgenstein’s observations regarding mankind’s experience of reality. There can, to paraphrase Wittgenstein, be no definite reality if there is no universally uniform reaction or perception to an event, object or thought.

Film is the most illustrative medium of the arts when put in terms of philosophical translation. Yet, in an issue of Cahiers du Cinema published in December 1956, Andre Bazin and Jean-Luc Godard became embattled in an argument over the validity of film art and its ability to reflect or capture reality.

Bazin’s article, “Editing Forbidden”, advocates a cinema of long takes shot with a deep focus. Bazin believed that it was the cinema’s responsibility to translate our reality as we see it to film, creating the illusion that we, the audience, are occupying the same space and time as the character’s of the film’s narrative. This translation of reality is more literal than Godard’s interpretation, standing in direct opposition of the theories of montage originated by Eisenstein and Vertov in the twenties. The films Bazin supported, such as the early films of Orson Welles and John Ford, present a perverted reflection of our reality, and therefore inherit the same non-truths as those outlined by Wittgenstein.

Godard’s article “Editing, My Beautiful Concern”, takes the opposite approach as Bazin’s. Godard argues that the films of Nicholas Ray, F.W. Murnau, and Fritz Lang, with their use of elaborate montage in the tradition of Eisenstein, present a cinematic experience closer to our reality, and perhaps even closer to a true reality in general. By breaking a narrative up into numerous signifying parts as opposed to a few, these films create a more powerful emotional and psychological reaction in the audience. Though most of these films are highly stylized and melodramatic, their ability, through montage, to capture human emotion does represent a more accurate reflection of the human experience. Despite the fact that these films are subject to Wittgenstein’s observations because they exist in our reality as works of art, within their own insular world they come closer to a true definite reality than those films advocated by Bazin.

For instance, a film by F.W. Murnau, such as Faust (1926), with its expressionist and romantic tendencies, creates a world within the film that is entirely reflective of the emotional and psychological truth of its characters that is indisputable to the audience, though the audiences’ own reaction is subject to debate. A less stylized film such as Hitchcock’s Strangers On A Train (1951) presents a world so much like our own that the truths experienced by the film’s characters are just as ambiguous and artificial as our own.

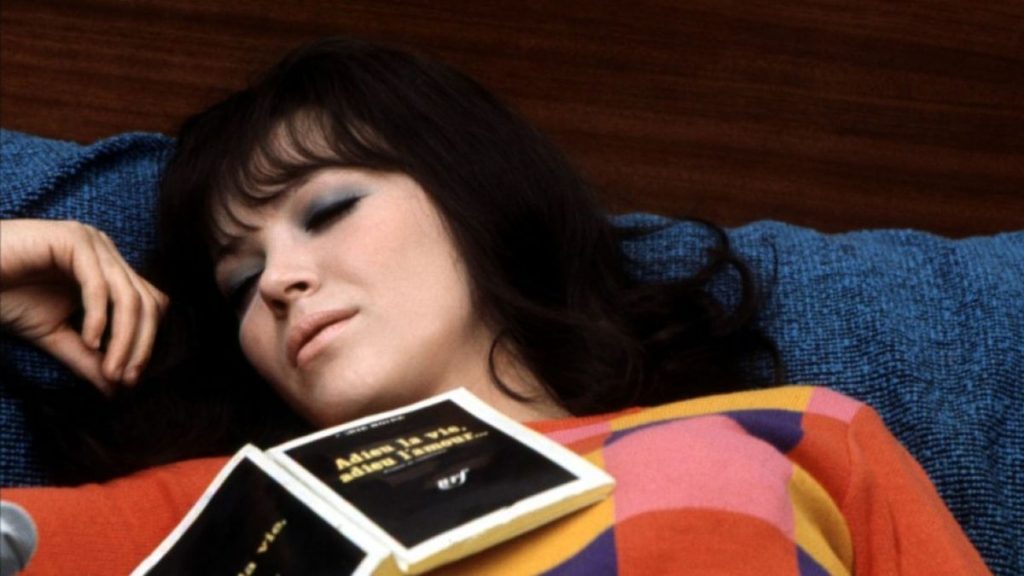

Godard’s observations are nonetheless in direct opposition of the basic language of film criticism. Godard’s film Made In USA (1966) utilizes cultural signifies constantly, just as it employs a complex editing strategy. Made In USA presents its audience with more truth through these tactics than most films, but is labeled avant-garde or experimental. Yet, a film like Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972) that utilizes a number of long takes, and avoids using signifiers of any cultural significance is labeled naturalistic. The paradox that exists here is the direct result of what Wittgenstein outlined to be mankind’s desire to make sense out of the chaos of his existence, to label and categorize what there is in the world. I don’t mean this in terms of the titles avant-garde or naturalism, but in mankind’s desire to confront reality on the terms of his experience of his perceived reality. That is to say, the reality of Last Tango In Paris is closer to our own in how it deals with the concept of reality as an aesthetic illusion whereas Made In USA avoids all confrontation with our perceived reality, preferring to manufacture its own world of truths.