“The cinema of postmodernity suggests a society no longer able to believe fully its received myths (the law of the father, the essential goodness of capitalism, the state, religious authority, the family). Yet it is also unable to break with these myths in favor of a historical materialist view of reality.”-Christopher Sharrett

If we accept Sharrett’s de facto definition of a postmodern society, we will find it realized in the paradoxical network of Metz’s cinematographic langue as employed by West German filmmakers beginning in 1966 and continuing through to 2016 in many respects (particularly with Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise Trilogy). West Germany was the pinnacle of postmodernism. Shame, guilt, fear, and the necessity of economic rebirth mandated a national amnesia. As if German identity had been on an extended hiatus between the mid-nineteenth century and the 1950s. Desperately, post-WWII West Germany came to define itself through appropriated American popular culture and the myths and folklore of Bavaria. Sharrett points out, rather astutely, that the myths of a postmodern society are no longer useful as myths, for they carry no true belief. Thus, this is the paradox of Young German and New German Cinema.

Two generations of German filmmakers mined the past, realigned, and redressed it in a series of films whose intention was to debunk these mythic accounts with the intention of centering them on the contemporary desire to define the “self”. The “self” of such films is typically an outsider, a superman of sorts, a homosexual, an immigrant, or a woman meant to represent that which is German. Werner Herzog does this explicitly in The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser (1974) and Heart Of Glass (1976), Rainer Werner Fassbinder also employs a similar tactic in Die Niklashauser Fahrt (1970). Other German filmmakers asserted a new “Germanness” by aligning in opposition to American culture as opposed to Germanic myth, such as Wim Wenders. The most explicit champion of a “New German” identity could be found in Hans-Jürgen Syberberg and his films.

Unlike a majority of his counterparts, Syberberg does not restrict his films to the traditional narrative three-act structure. Ludwig – Requiem für einen jungfräulichen König (1972) and Karl May (1974) are epics dependent upon a synthesis of opera, set design, rear projection, performance, and cinematic montage. In the history of the cinema, no other filmmaker can lay claim to having constructed Eisenstein’s proposed synesthesia on such a spectacular or massive scale. Syberberg’s postmodern strategies juxtapose signifiers representing the immediate German past and the contmporary, pursuing their contrasts to the point of an implosion of meaning, as if he were wiping away cobwebs, unmasking denial, in a celebration of German identity and German cinematic heritage (a heritage, as for Herzog, rooted in the works of Pabst, Lang, and Murnau).

Syberberg and Fassbinder represent two of the most renowned names of German Cinema. Though, beyond Germany itself, little is known of Werner Schroeter who represents an aesthetic forerunner to Fassbinder and Syberberg. Both filmmakers have acknowledged Schroeter as a significant influence on par with that of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet in shaping the “alternate style” of New German films (a style opposed to the realist and the literary traditions as exemplified by the films of Helma Sanders-Brahms, Alexander Kluge and Volker Schlöndorff).

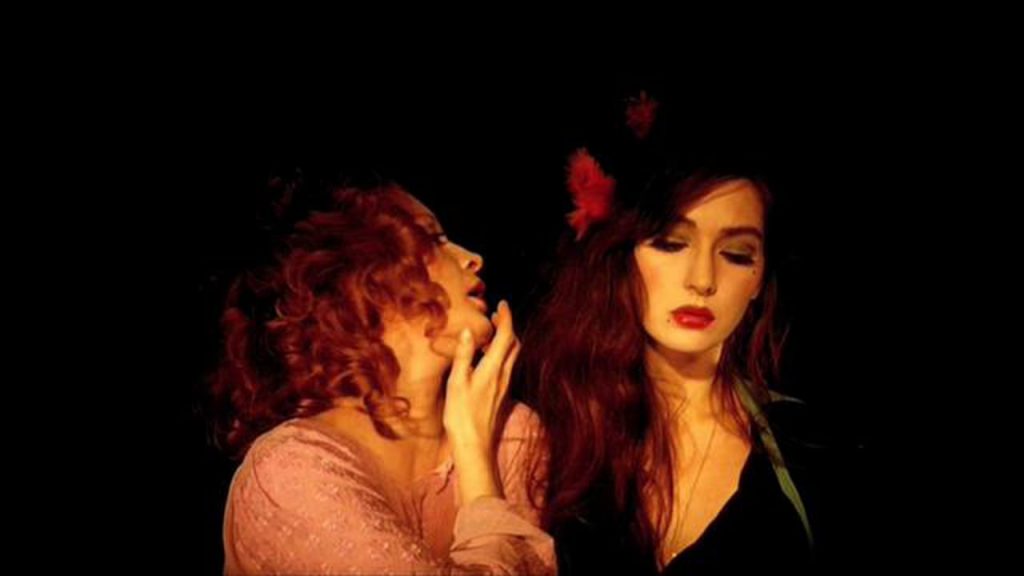

Syberberg’s spectacles of a postmodern synesthesia invariably have their root in the visual language of Schroeter’s Eika Katappa (1969) and Der Tod der Maria Malibran (1972). The plasticity and expressionism of Schroeter’s set pieces are clearly echoed in Syberberg, as is Schroeter’s use of auditory cues lifted from Wagner and Verdi. Likewise, Fassbinder’s kitsch codification of histrionics within the context of classic German Romanticism are also born out of Schroeter’s films.

The need to define “self” that unifies the films and filmmakers of New German cinema across differing styles and approaches is also evident in Werner Schroeter’s films. However, Schroeter’s films find that identity in the “self” reflected. That is to say that the individual “self” of a character is found in the definition of that “self” as reflected by another character. A communal quality permeates Schroeter’s early features. Bands of outsiders, banished for their sexuality or race, or crimes, congregate in groups, creating a substitute family (a hallmark of John Water’s early films as well that also focus upon gay and outsider cultures). This renders Schroeter’s films in opposition to the maladjusted families that threaten “self” in the films of Fassbinder and other German filmmakers.

Schroeter’s short films also have an outsider focus with a historical preoccupation. His filmic meditation on Maria Callas is obsessive in its fetishization of the film’s subject. This fetishization carries over into the long close-ups that begin Der Tod der Maria Malibran. The beauty of unconventional beauty is Schroeter’s most personal preoccupation early in his career. In this way the very landscape of Schroeter’s psyche becomes part of the structure of his films, a singular anomaly in the canon of New German Cinema.

Historians such as John Sandford may relegate Werner Schroeter to the footnotes of New German cinema history, but Schroeter’s actual importance is critical to understanding the dialogue between the avant-garde and the mainstream in German cinema as well as the linear trajectory of influence. Werner Schroeter’s cinematic standing is perhaps better understood beyond the confines of Germany. Schroeter’s “outsider” persona, the homo eroticism of his work, and the repertory nature of his productions are the German equivalent to either Jack Smith or Andy Warhol. Whilst his highly personal mode of filmmaking along with the camp elements of his visual style are akin to the 16mm features of Derek Jarman.

Personally the experience of watching Der Tod der Maria Malibran was shattering in both its beauty and its poetry. It is perhaps the most moving cinematic experience since I first saw Kenji Mizoguchi’s Yōkihi (1955). So I would like to conclude by quoting Werner Schroeter himself. He better than most can find the proper words to articulate the effect truly substantial art has upon the spectator, which, needless to say, is Schroeter’s primary motivation and the source of his “Germanness”.

“It would be absurd to argue that the desire for beauty and truth is merely an illusion of a romantic capitalist form of society. Without a doubt, the desire for an overreaching, larger-than-life wish-fulfillment, which we find everywhere in traditional art, which by all means includes the modern trivial media such as the cinema and television, signifies a need that is common to every man; for his all-too-definite appointment with death, the single objective fact of our existence, is an a priori forfeit of the prospect of tangible happiness.” (Werner Schroeter, Der Herztod der Primadonna, 1977)