In 1962, with the issuing of the Oberhausen Manifesto, New German Cinema began. For twenty years a generation of German filmmakers produced small, personal and decidedly nationalist films in response to the Americanization of West Germany and the stagnation of any national unifying notion of Germany. Of these filmmakers, only one fixed himself to narrative subjects that existed almost exclusively outside of the contemporary West German setting, preferring the Romantic and Operatic of German folk tales and literature, his name is Werner Herzog.

In his book The Altering Eye, Robert Phillip Kolker refers to Werner Herzog as the “self appointed Holy Fool” of New German Cinema, citing Herzog’s rejection of contemporary subjects as a lack of seriousness, an evasion of social commentary and national urgency. Though, in superficial terms, this may appear to be a valid assessment of Herzog’s position within the movement (a position he continued to nurture in films such as Harmony Korine’s Julien Donkey-Boy and Zak Penn’s Incident At Loch Ness), such an assumption negates the unifying obsession at the heart of almost every Werner Herzog film, the investigation of what it means to be an outcast.

This obsession, appearing in varying degrees of abstraction reoccurs in not just Herzog’s films, but also in the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Alexander Kluge, Wim Wenders, and Volker Schlondorff. The working-class subjects of Wenders’ early films as well as those of Fassbinder focus on the contemporary disenfranchisement of various social demographics within German society. In contrast, Herzog’s protagonists handle the same issues of isolation, but within the singular context of the film’s narrative. The most dramatic example of this is in Herzog’s The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser (1974). Hauser, raised in isolation till his release in his early twenties, must adapt to the German society of the late eighteenth century just as that society must in turn adapt to his sudden emergence. Indirectly, Herzog is presenting his commentary on West Germany’s reemergence as a serious world power in the early seventies for the first time since the end of WWII. The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser then serves as the same social commentary as lets say Wenders’ The American Friend (1977), yet remains far more distinct in its ability to retain a national notion of Germany by framing its commentary within the narrative of one of Germany’s most infamous folk tales.

The device I have outlined within Herzog’s film The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser recurs in all of Herzog’s period dramas of the seventies, from Heart Of Glass (1976) to Woyzeck (1979). Still, it isn’t entirely surprising that Kolker overlooked this aspect of Herzog’s style. One must remember that America’s perception of Herzog today is still very much what it was when he first became known on the Art House circuit in 1972 with Aguirre The Wrath Of God. The stories and legends that have arose around Herzog over the years, though some are true, often overshadow or at least color the critical readings of his films. Herzog himself has propagated many of these myths himself, and has done very well to preserve them by taking only the most bizarre acting assignments in other filmmakers’ movies. That said, it seems only logical that Kolker’s equating Herzog’s own presumed obsessive behavior with that of the protagonists in his films is the product of Herzog’s own presentation of himself.

A critical misinterpretation of Herzog’s early filmography is only half the problem with the American understanding of the director’s work, the other half lies with the audience itself. As with any foreign film in the seventies, Herzog’s films weren’t likely to screen in America till they had already played in West Germany for a year. Couple that delay with America’s ignorance of West German politics and social movements and the reasons for all misinterpretation become clear. If one is unaware of the social problems facing West Germany, how is one to interpret or even recognize Herzog’s commentary in The Enigma Of Kaspar Hauser? What if, in addition to socio-political ignorance, one was also unaware of the Kaspar Hauser folk tale? Herzog’s film would then probably read as the obsessive musings of a demented German philosopher, an image of Herzog that many Americans carry today. It is the other worldly reading I have just described of Herzog and his films that has become a generalization of all German films amongst American audiences. It doesn’t matter if Herzog is involved or not, the popularity of his “other-worldly” cinema in America is the basis of America’s expectations of a German film, Wenders, Fassbinder, Syberberg, Kluge, or otherwise.

Werner Herzog’s last film to adhere to a distinctly German world view was his first Hollywood film, Invincible (2001), which is also the first of three films that function as character studies of protagonists in environments that reflect their inner psychological turmoil; Rescue Dawn (2007) and The Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans (2009) being the other two. Invincible follows a Jewish strongman struggling to survive as a performer in Nazi Germany. Herzog’s two follow up narratives have Americans as their protagonists who are forced to navigate two American tragedies; the Vietnam War and New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. These three films represent a closing down of Herzog’s political and social commentaries, preferring to investigate internal moral dilemmas and personal struggles. Herzog’s internalization at this late point in his career is the direct result of the documentary films he had begun to make in 1997, beginning with Little Dieter Needs To Fly. Little Dieter Needs To Fly (1997) along with Grizzly Man (2005) represent documentary portraiture along the same lines as Herzog’s own documentary shorts made for West German television. This style of documentary filmmaking emphasizes intimacy, and through observation offers an astute psychological analysis of a subject. This mode of investigative filmmaking is the primary purpose of Herzog’s first three American narrative features.

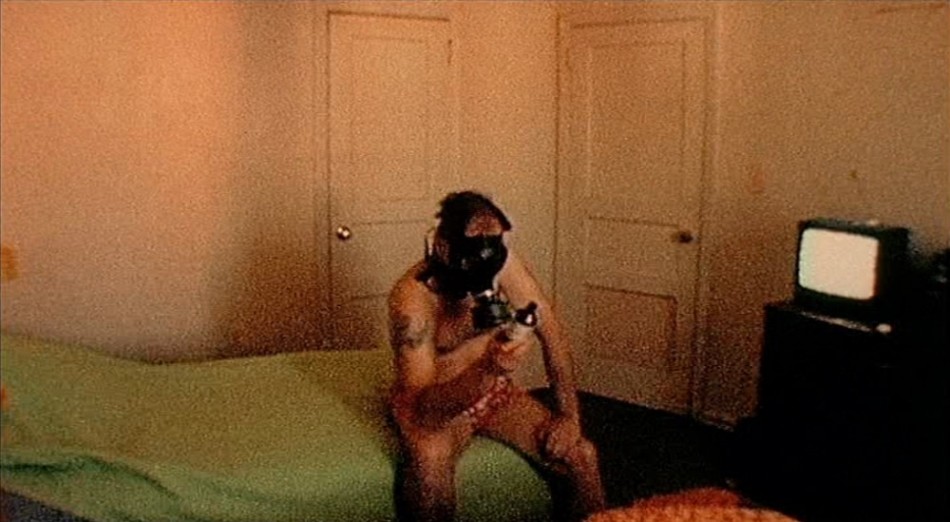

But Herzog would close in even more in his narrative work with his feature My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? (2009). This film, unlike the three that preceded it, is not grounded in any national catastrophe, but rather unfolds as a psychological thriller. In essence Herzog has retreated from the wider context of German heritage in his earlier films and the national crises of his later films to explore exclusively the cause and effects of obsessive behavior.

Though Herzog’s aesthetic has transformed and narrowed itself down in terms of portraiture, the appraisal of his American films by Americans is still within the context of an “other-worldly” German filmmaker making films in Germany. Even without the distinctly German themes of his classic period, Herzog’s films are still understood to be imports, with vague signifiers and an elusive context. Werner Herzog as a brand has become more significant then Herzog the artist. Most people I have encountered who are familiar with his later work still asses and read Herzog’s films as though they were derivative of a context akin to Signs Of Life (1968) or Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), going so far as to say “his films don’t usually seem to make sense” (anonymous). What the image of Werner Herzog has become in American culture prevents Americans from understanding and engaging Herzog’s narrative films within the context of his aesthetic evolution.