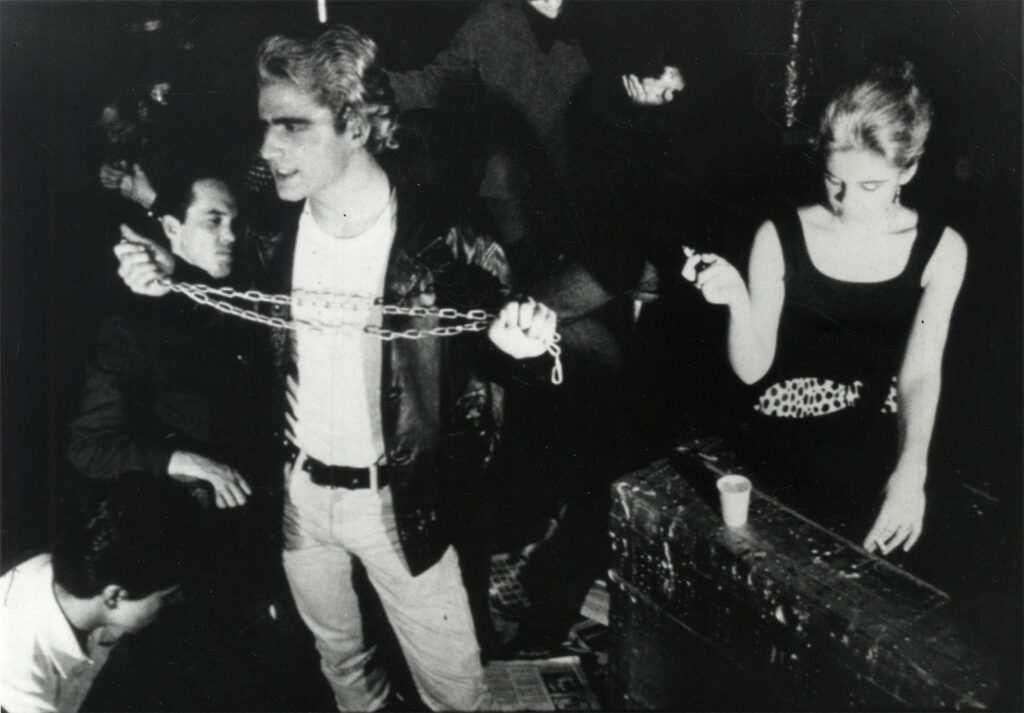

Andy Warhol’s film adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange,Vinyl (1965), opens in a close-up just like Stanley Kubrick’s version. Vinyl begins with Gerald Malanga’s face filling the screen. He is our protagonist; a sadistic, prowling youth let loose on the world. From Malanga’s face Warhol’s camera pulls back to reveal a corner of the factory where people seem to have gathered behind Malanga into a kind of triangular shape. Edie Sedgwick is seated on Malanga’s right smoking cigarette after cigarette. Positioned behind Malanga is Superstar Ondine who will be Malanga’s favorite victim in the film. Once this wide shot is established Warhol’s camera never moves again.

There are no titles in Vinyl. Once the camera has moved back into a wide shot Malanga simply speaks aloud “Andy Warhol’s Vinyl“. Where normally, as in Kubrick’s film for instance, those words would appear in text above and below Malanga and his co-stars it is the star himself who speaks these words, who becomes a conduit not just of the illusion of a narrative world but a mechanism in the more plastic functions of a film.

The dialogue between Warhol’s films prior to Paul Morrissey’s arrival and Hollywood cinema is essential to understanding what Warhol is doing. Really what’s important is what Warhol isn’t doing but rather gesturing towards. Malanga’s relative position to the camera doesn’t vary much. He moves forward and backward within the center of frame. He is the star. The camera, though fixed, retains the ability to capture Malanga in close-up and medium shot in addition to the wide. This relationship between the star performer and the recording device of the camera suggests the tracking shot without any locomotion on the part of the camera itself.

As for the content of Vinyl the purpose isn’t so much to adapt Burgess’ novel in the traditional sense but rather to distill it to its most fundamental concepts. The effect of this is a series of tableaus wherein Malanga either dances in sexual euphoria or enacts sadistic routines on his retinue in an effort to assassinate that part of himself which he finds contradictory. Of course that aspect is his own homosexuality which in Burgess’ novel is only ever a subtext. In Warhol’s vision of A Clockwork Orange it is society’s unacceptance of homosexuality that triggers Malanga’s protagonist and inevitably leads to his forceful rehabilitation and conditioning.

Vinyl, despite all of the “play” happening on camera, is Warhol’s darkest film of this period. It effectively evokes the “queer outlaw” motif of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963) but places it in a broader political context where there is a reckoning with the mainstream of American culture. Warhol’s allusions to James Dean and Marlon Brando with Malanga’s character connect Vinyl to the closeted queer heart throbs of the previous decade. The mechanisms of the cinematographic langue exist in Vinyl only by means of the performers’ interactions with the camera over a duration of time. It’s an effective and moving film and probably one of Warhol’s greatest achievements as a filmmaker.