From making quickie B-Movies for Roger Corman to working off-Broadway with Elaine May, Jonathan Kaplan had seemingly done it all. But as Corman’s tenure as the King of B-Movies waned in the eighties, so did Kaplan’s career as a film director. However, all of that changed when Kaplan took the chance to direct Jodie Foster’s passion project The Accused (1988). Now, in the third decade of his career, Kaplan was at the forefront of the burgeoning erotic thriller genre of the late eighties and early nineties.

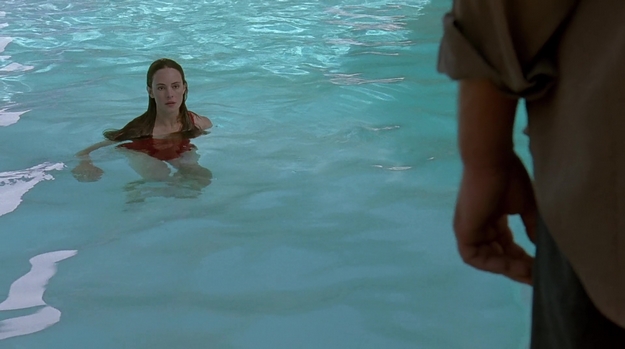

Kaplan’s subsequent film Unlawful Entry (1992) tells the story of an upper middle class couple (Kurt Russell and Madeleine Stowe) who are terrorized by a seemingly good cop (Ray Liotta) after their house is broken into. Unlawful Entry is a thriller that exploits the paranoid fantasies of the white male bourgeoisie. From the commodification of the woman-child to the anxieties behind racial profiling, Unlawful Entry examines how the apparatus of the police in our society enforce white male middle class values.

Liotta’s villain cop seems all peaches and cream at first. But as Liotta’s character fixates on Stowe and conspires against Russell that veneer begins to fade. The gradual reveal of Liotta’s true nature in Unlawful Entry is, in essence, the active form of Russell’s innermost fears and prejudices. Where Russell fears Black Americans as inherently criminal, Liotta actively and violently victimizes them. Where Russell attempts to control Stowe, Liotta actively traps her quite literally in her own home. The relationship between the two men is the duality of the conscious and subconscious raging in a battle externalized as two unique characters.

This focus on white male insecurity and authority relegates Stowe and the few other women in Unlawful Entry to the background. Within the political economy of the film women are little more than trophies to be won and kept by an alpha male. The little development that Unlawful Entry allows Stowe is to establish that she has a paternal fixation. This suggests that Stowe, as the representative of her sex in Unlawful Entry, is beholden to the power of the phallus over which Liotta and Russell struggle for control. Stowe’s character development reiterates and affirms the centrality of hyper masculinity that concerns the film.

It’s easy to see the intertextuality between Unlawful Entry and Deadly Hero (1975) as both films work to dismantle the illusion of white middle class security by revealing the moral and ethical corruption of policemen characters. Kaplan’s direction sees this process as essential to Unlawful Entry and works in collaboration with Liotta to create a truly evocative and disturbing portrait of the corruption of power. Liotta perfectly presents the everyday as something menacing and sexual until he is actively dangerous and the facade of civility drops away. For Liotta, Unlawful Entry is a tour de force for the actor who made playing bad guys his art.

In the canon of thrillers made in the nineties, Unlawful Entry is an unsung masterpiece. It effectively brings the sleaze and danger of the drive-in features of the seventies into the post-Adrian Lyne glossiness of the affluent nineties. Kaplan, with all of his experience, is a filmmaker perfectly attuned to bridge these aesthetics to create an affecting post-modern spectacle propelled by dynamite performances.