Film director Ronald Neame is best known for his two later day American productions The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Hopscotch (1980). However, Neame’s personal favorite, and most significant film is Tunes Of Glory (1960), a military drama starring Alec Guinness and John Mills. The author of the book on which the film is based, James Kennaway, penned the screenplay forTunes Of Glory. Upon the initial release of Tunes Of Glory, the film garnered a number of awards and nominations, ensuring Neame’s transition into bigger Hollywood productions such as I Could Go On Singing (1963). Despite the commercial success Neame found in his American work, he would never again achieve the critical acclaim and renown of Tunes Of Glory.

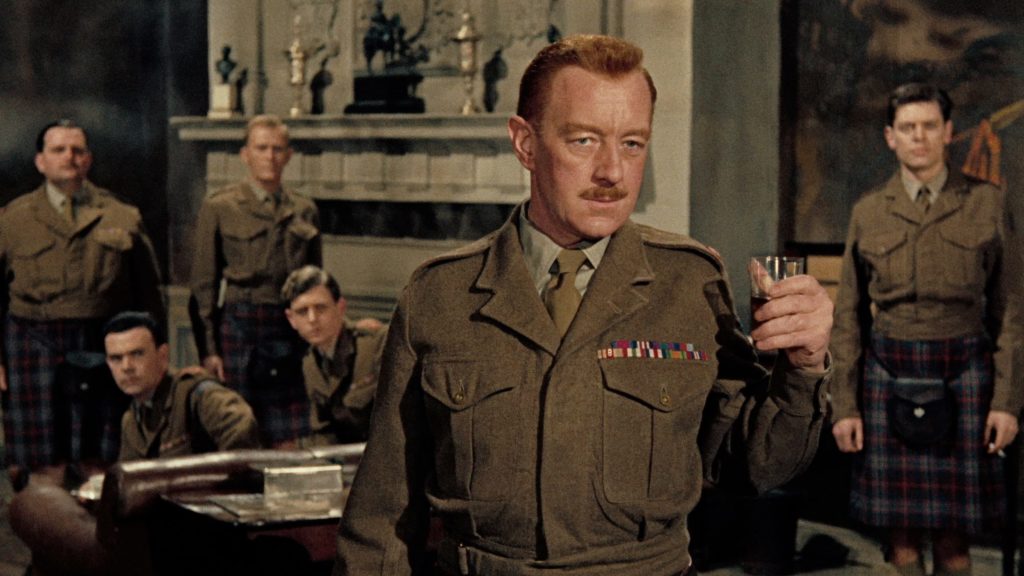

The film follows the relationship between two Colonel’s in Her Majesty’s Army, Jock Sinclair (Alec Guinness) and Basil Barrow (John Mills). Sinclair had once been a piper for the Highland Regiment he commands, having made a career out of the army, working his way up the ranks during WWII. In contrast, Barrow was born into the upper echelon of military families, achieving his rank via an Oxford education. The men of the regiment hail from a myriad of backgrounds, but hold steadfast in their loyalties to Sinclair, even when Barrow replaces Sinclair.

Though the dramatic action of Tunes Of Glory is motivated by the power struggle between Sinclair and Barrow, the film carries with it a definite urgency, underscored by a similar conflict of the classes represented by both men. In opposition of Sinclair’s bawdy personality and the fatherly relationship he has with his men is the distantly cool and impersonal perfectionism of Barrow, a product of high society and a college education. In their power struggle, both men take advantage of their class differences when berating one another. For instance, Barrow forbids his men from raising a ruckus when dancing, citing Sinclair’s lack of breeding for the lax rules regarding the gentlemanly behavior of his men. Not to be out down, Sinclair makes several references to Barrow’s unfamiliarity with the needs of the lower ranking men, alluding quite overtly to the snobbery and pretension of the upper class. Of course, the issue of class functions as a subtext in Tunes Of Glory, designed to covertly ridicule the dynamic divisions in wealth that existed in Britain at the time. In some cases, these allusions to such a division are so skillfully hidden within the main text of the film that one only notices them upon a second or third viewing.

The power struggle between Sinclair and Barrows reaches a climax after Sinclair assaults a Corporal who had been engaging in a romance with Sinclair’s daughter (Susannah York). The assault is a court martial offense, but due to his lack of popularity and inability to control the men under his command, Barrow is unable to act on his own. His priorities are to the good of the Battalion’s image and to his military lineage. As a precaution, Barrow consults with Sinclair’s close friend turned social climber Major Scott (Dennis Price) on how to proceed. Scott advises that the court martial goes forward. Barrow’s plan never comes the fruition once the men rally to have the matter resolved internally, preserving Sinclair’s rank and duties. At this point, Sinclair has seemingly won the battle; the allegiance of his men is entirely his since Barrow’s arrival at the start of the film. It’s at this point that Barrow realizes that the command was never truly his, that he has failed to live up the obligations prescribed by his family’s heritage and traditions. After conferring with Major Scott about his personal failure as a commander, Barrow retires to the washroom and shoots himself in the head.

What Tunes Of Glory does so well is articulate the relationship between an officer, his men, and the honor of his office which he is sworn to protect. One must understand that each command is inherently tied to some tradition whose very existence an officer is expected to maintain. This gets to the heart of the power struggle. Superficially, a fight for a command is partly about power, but it is mostly about the honor of that position and the glory that goes with it once that position is achieved. However, that position is nothing more than a title without the confidence of the battalion to back it up. The revelation that Barrow had nothing more than a title is what killed, for as he says in the film, “I ate, slept, and dreamt about this command since I was born”.