Long before the cinema existed there was the circus, and the circus was one of the most popular entertainments in the world. So it is no surprise that the circus itself would become the subject of a number of films, from Big Top Pee Wee (1988) to The Greatest Show On Earth (1952) to Mr. Lonely (2007). Yet, very few films seem to do the circus any justice. Conceptually, by allowing the camera to control the audiences’ gaze via a totally subjective point of view camera, Jonas Mekas’ Notes On The Circus (1966) realizes the energy and titillation of circus goers. But in the field of narrative filmmaking only two American films spring to mind as depicting the circus as the social structure that it is for its performers. One is Todd Browning’s Freaks (1932); the other is Carol Reed’s Trapeze (1957).

Trapeze is indebted to Freaks in some unexpected ways. Freaks did, after all, provide the blue print for creating a successful tableaux of circus performers as an ensemble navigating the social hierarchy of the big top. But Trapeze is not a gothic morality tale; it’s a melodrama about an ill-fated love triangle. And unlike Browning, Reed was a strict genre filmmaker till that point, working heavily with the espionage drama, which was so popular in the immediate wake of WWII. Where Freaks focuses on the lowest members of the circus totem pole (those in the freak show), Trapeze focuses its narrative on the romantic heroes of the circus, the trapeze artists.

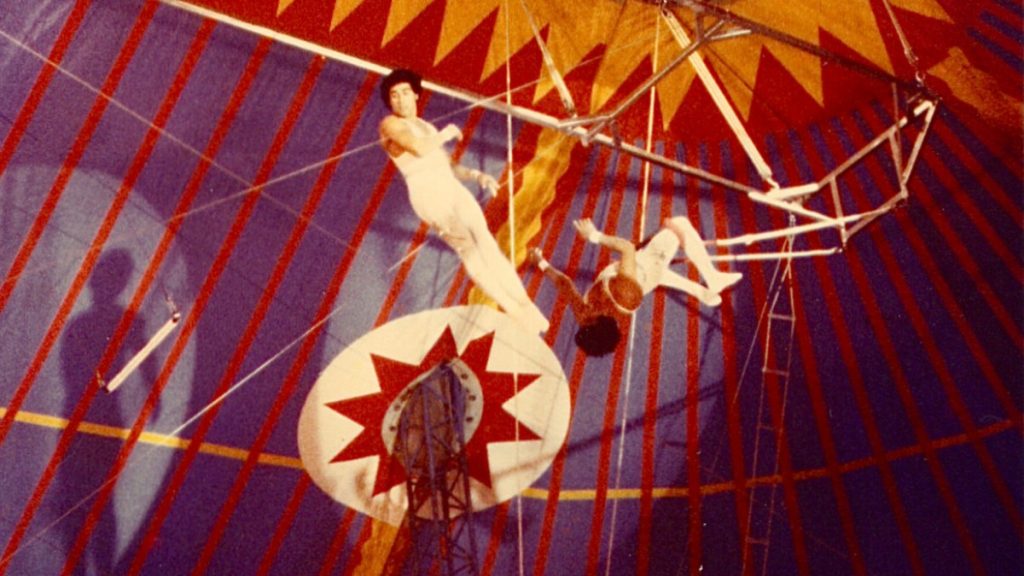

Mike Ribble (Burt Lancaster) is a retired high-flyer, working the rigging at a French circus. He had injured himself performing the most difficult trick for a trapeze artist, the triple somersault. One day, Tino Orsini (Tony Curtis) arrives. An accomplished trapeze artist himself, Tino enlists Mike to coach him, be his catcher and teach him the infamous “triple”. All is going well, and the pair is preparing for opening night when Tino falls for Lola (Gina Lollobrigida), who has just lost her own act. Soon, she’s playing Tino, vying for a place in the trapeze act. Mike is resistant at first, and soon Lola is pitting both men against each other.

The narrative is familiar and a little stale, relying heavily upon established genre conventions. It is Reed’s skill as a director that gives the film an added depth. He peppers the film with secondary characters. These characters reoccur, are given dimension, and in some cases are even scene-stealers like Johnny Puleo. In addition, Reed’s mise en scene is overflowing with acts, humor, and general bustle, all of which is imbued with a clear sense of authenticity. According to Burt Lancaster’s biographer, Gary Fishgall, the production booked a number of genuine circus acts to fill out the mise en scene to realize Reed’s vision. This is the strength of the film.

Browning never had the budget to fill Freaks or, his other circus picture, The Unknown (1927) with Reed’s degree of authenticity. Likewise, DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth preferred, to either Browning’s minimalism or Reed’s mise en scene, pure spectacle and artifice. In fact, it was DeMille’s film that inspired Lancaster (a former circus performer himself) to produce Trapeze as a means of giving movie audiences a glimpse of “authentic” circus life.