Way, way back when I was in film school my favorite professor gave me a bunch of videocassettes of movies that were, at the time, quite hard to come by. A lot of these tapes were transferred from the university’s 16mm library. One of the films was David Holzman’s Diary (1967). I came to that film already a fan of L.M. Kit Carson but finished the film a staunch devotee to James McBride.

Lately James McBride has been experiencing a sort of mass rediscovery courtesy of Fun City Editions’ release of his film Breathless (1983). If James McBride joins the likes of Brian DePalma and John Cassavetes in the canon of great American filmmakers for a new, younger generation I will be happy. When I was at film school none of my classmates even knew who James McBride or L.M. Kit Carson were. If that is corrected then American cinephilia will be far better off. Which brings me to McBride’s The Wrong Man (1993).

For a long while now The Wrong Man has languished in true obscurity. This pulpy neo-noir has never gotten an upgrade to Blu-Ray or a proper restoration. Like so many direct-to-video releases from the nineties The Wrong Man seems to only exist as a grainy rip on youtube these days. The fact that so few people have taken direct-to-video films seriously is a tragic oversight. Some of these films, including The Wrong Man, are far more interesting than many of the films that received a theatrical release and the laudits that come with it.

The Wrong Man continues McBride’s deconstruction of classic Hollywood myth making. In an overt homage to Orson Welles, The Wrong Man draws inspiration from Mr. Arkadin (1955) and Touch Of Evil (1958). McBride, like Welles, chaffed at the reins put in place by the studios and sought to make his films via alternative avenues. Welles went to Europe while McBride hit the straight-to-video circuit. But these two filmmakers have more than one thing in common as artists. Each in his own way sets out to re-write or redefine the nature of classic narrative filmmaking. Just as Mr. Arkadin and Touch Of Evil subvert many of the tropes of noir, The Wrong Man completely disassembles the genre piece by piece.

Really there are only thirty minutes worth of filmic plot to The Wrong Man even though the film has a runtime of 102 minutes. McBride introduces his protagonist and no sooner has him falling into a crime scene only to become suspect number one. On the run, the hero of the film meets a sadomasochistic married couple and joins them as they head south. The hero falls for the femme fatale wife almost immediately, only for it to be revealed that her lunatic husband is responsible for the crime that the hero is suspected of committing. The hero and the femme fatale decide to run off together when the police arrive and everything goes to hell.

These are all essential film noir beats that, over the course of the film, are constantly delayed or repeated as the trio navigate their conflicting desires. In these scenes McBride lays bare the subtextual workings of film noir; the latent sexualities, the self-destructive impulses and the fearful compulsion to lie. The Wrong Man is Robert Siodmak in slow motion so that every seam and every stitch can show. The cops are more hapless, the hero is more helpless, and the femme fatale is more deluded than ever before.

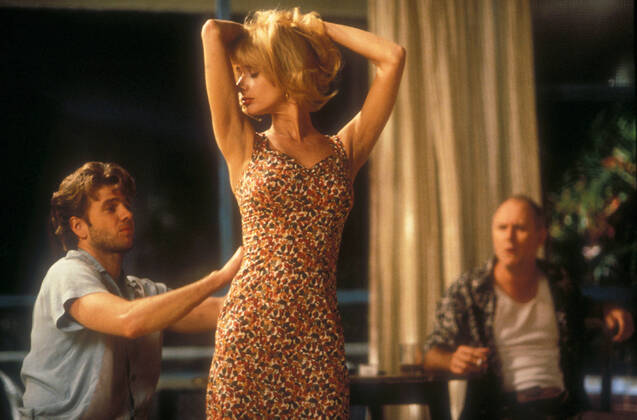

Like Guy Van Stratten in Mr. Arkadin Alex Walker (Kevin Anderson), the hero of The Wrong Man, is a sailor who happens into the world of crime. In place of Orson Welles McBride gives us John Lithgow as a violent, manipulative kingpin of a small time smuggling operation. What McBride doesn’t barrow from Welles is the Rosanna Arquette character who is equal parts Ava Gardner in The Killers (1946) and Jane Powell in The Female Animal (1958). Each member of this threesome epitomizes the fundamental building blocks of characterization in noir. What McBride does to change them is to make them human rather than caricatures of selective human impulses.

Film Noir reflected the popular psyche in the aftermath of WWII where as McBride’s deconstructionist approach to neo noir attempts to catch a glimpse of human individuals in that reflection. On a philosophical level this puts The Wrong Man in the tradition of Nicholas Ray (and by extension Jean-Luc Godard) rather than Orson Welles. McBride’s singular obsession throughout his filmography has always been to find humanity within its own media constructs: David Holzman’s Diary addressed the system of image and spectator where Breathless looked at the idealized representations of human form and virtue in matinee idols and comic books. The Wrong Man takes the collective catharsis of film noir and identifies the individual tragedies that form the genre’s plastic gestures and baroque set pieces.

In an age where the post-modern pillaging of older films to create an impersonal, uninteresting collage passes for cinematic art the rediscovery of films like The Wrong Man are vitally important. McBride’s film may not be the most accomplished film on a technical level, but there is more thought and reflection in every scene than in the entirety of a Quentin Tarantino or Wes Anderson film. The Wrong Man needs rescuing and it needs it now.