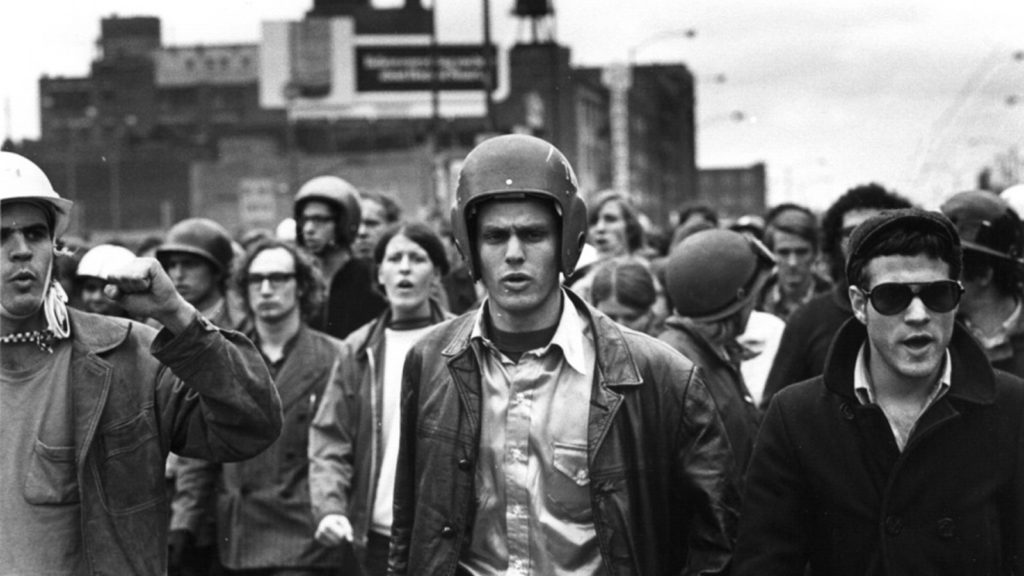

Sam Green and Bill Siegel’s The Weather Underground (2002) represents something unique in almost all American political documentaries, the convincing illusion of objectivity. Part of this may be accounted for by the subjects’ cynicism, and part of it in the structure chosen for the film. For unlike Marker’s film, The Weather Underground chooses to intertwine both the narratives of the radical Weathermen and the conservative law enforcement agencies tasked with apprehending them. The method of intercutting back and forth between the Weathermen story and the FBI story is powerful, particularly when, in contemporary interviews with the persons involved, neither the once radical nor the former FBI men sound all that different in terms of their rhetoric of today. In fact, both sides of the conflict seem to exhibit total disbelief in their former lives, spanning some fourteen years between 1968 and 1982.

Siegel and Green’s representation of violence is also democratic. If The Weather Underground shows its audience an instance of one of the Weathermen’s bombings, then that will be countered with an instance of FBI injustice or police brutality. Siegel and Green’s thesis is not dependent on a victim/victimizer relationship between subjects, but looks to determine how one side’s violence fed another’s, perpetuating in cyclical fashion an endless stream of attack and counter-attack.