The Running Man (1987) continued a trend in American mainstream media of critiquing late Reagan-era conservatism through the moral decay of commercial public television. Like Robocop (1987) and Frank Miller’s comic The Dark Knight Returns (1986), The Running Man imagines a world in the distant future where the expression “opioid for the masses” is taken literally with television as the great pacifier of political and social resistance to a totalitarian state. Although The Running Man shares certain aesthetic qualities and political views with Robocop and The Dark Knight Returns, the film itself barrows so much from Le prix du danger (1983) and Das Millionenspiel (1970) that it actually lost lawsuits charging plaigarism.

The political climate in America, particularly on the right, was very different when Stephen King penned the novel The Running Man than what it would become when the film was released. The film The Running Man, set in 2017, predicts the cult of personality and the total disregard for truth, law and civil rights that have come to define the Republican Party in the years after the Obama presidency. What looked like fanciful extremism in the service of political satire in 1987 has become so close to the reality of the 2020s that The Running Man, despite all of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s corny quips, has become a tale of terror on an Orwellian scale.

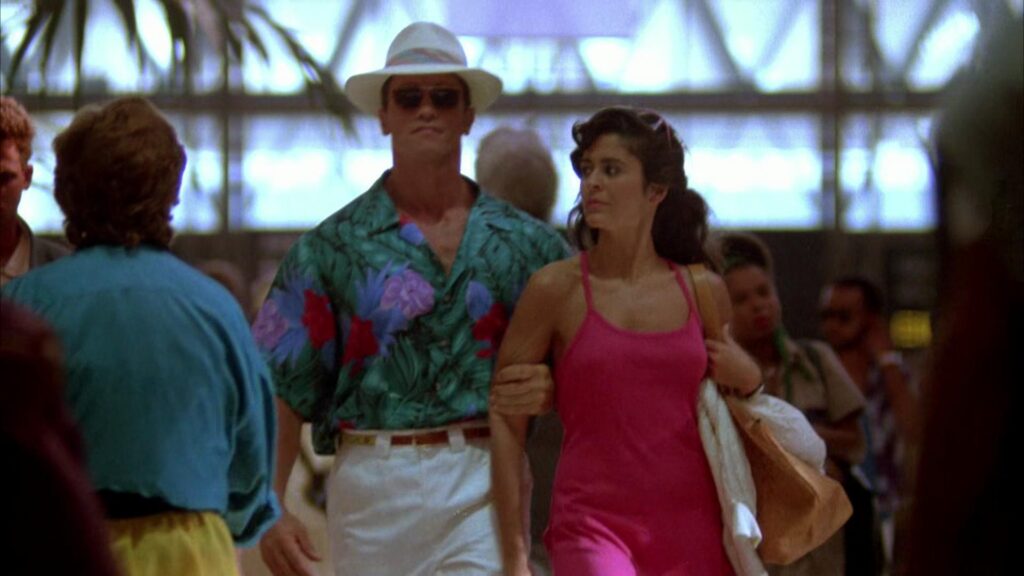

What’s so interesting about films like The Running Man and Robocop is that while they exist as cultural critiques they simultaneously succeed as adrenaline inducing escapist spectacles of phenomenal craftsmanship. These are white knuckle action pictures, full of testosterone, for the thinking person, the intellectual. One can thrill to the brawling sadism of the fight between Predator (1987) co-stars Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jesse Ventura and still reflect on how the film critiques popular media’s role in our collective lives on a daily basis. “The Running Man” show in The Running Man is part televised trial, part WWE, part game show, and featuring ample doses of Maury Povich-like shenanigans.

Actor turned director Paul Michael Glaser handles the kinetic scenes of ultra violence in The Running Man with an adept hand though he seems more at ease with Richard Dawson’s dialogue heavy scenes. The Running Man never achieves the comic reflexivity of Robocop nor the suspense of Predator, but it suffices as a totally engaging adventure. The biggest oversight on Glaser’s part is that the coverage of the climactic battle in the television studio lacks the coherency necessary to convey where shooters and targets are located and which viewers are watching which screens.

In the canon of Arnold Schwarzenegger movies The Running Man has become something of an unsung classic. Though it may be Arnold Schwarzenegger’s most socially and politically relevant movie today, it is overshadowed by the star-as-signifier iconography of The Terminator (1984), the success of Predator, and the novelty of Twins (1988). As the election year draws near, it is time to reassess Schwarzenegger’s most underrated adventure of the eighties.