“If only he had realized all his ideas, he could have become one of the greatest.”-Sergio Leone

Sergio Corbucci has long-lived in the shadow of Sergio Leone. One cannot read about Corbucci’s work without the inevitable comparison to Leone, despite the fact that the two men have highly contrasting styles and aesthetic concerns in their approach to the Western genre. Corbucci’s films are noted for their loose style and hyper energy. Sometimes a particular sequence seems muddy or out-of-place, but the overall feeling of Corbucci’s style is one of unbridled enthusiasm for the genre, very similar to Luc Moullet. What the Italians did with the Western genre was to re-appropriate it after it had been filtered through Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961). The Italian Western, Corbucci’s films included, champion an anti-hero, depict governments as corrupt, and exploit the violence and sexuality of the genre.

The Great Silence (1968) sees Corbucci taking the Italian Western a step further. Though the Italian Westerns added a grittier element to the genre, they still followed the basic principles of good and evil that can be traced back to Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail and even further. The Great Silence shatters this balance of negative and positive, concluding with a bleak, existential morality.

It’s interesting to note that The Great Silence pre-dates the shifts in the American Western aesthetic that would occur in the seventies. Robert Altman’s meditative Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) would be the first to outright contradict the forms one associates with the Western film. Prior to that, American filmmakers such as Sam Fuller, Monte Hellman and Anthony Mann preferred anti-heroes working within a corrupt moral system but still maintained the regular signifiers and conformed to the basic narrative expectations of the Western.

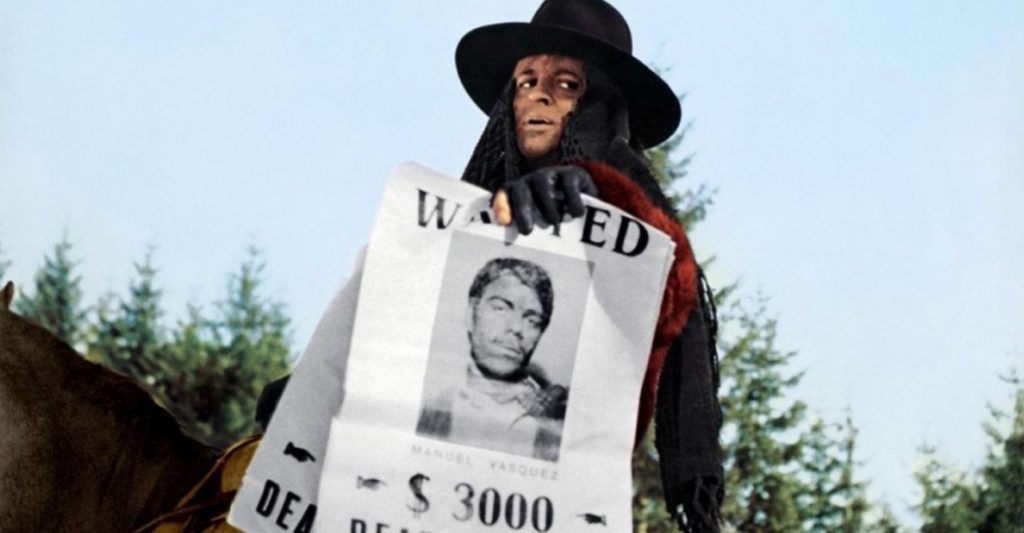

The Great Silence is like any other Corbucci film. It’s violent, the characters are corrupt, the hero has a gadget gimmick and an odd name (in this case Silence) and the villains are sadistic. Yet, in the last act when Silence (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is expected to defeat his nemesis, despite his wounds, he fails. Silence is murdered by the man he should have defeated, Locco (Klaus Kinski). As a result of Silence’s death the starving townspeople living in exile, because of their differing ethnicity, are butchered by Locco and his gang. This ending speaks to Corbucci’s bleak outlook on life. For him the righteous are not always victorious.

That this ending comes in a film who, until its end, fits so nicely into the regular genre makes it all the more shocking and impactful. The Great Silence, like Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), addresses the Johnson County range war with a contemporary leftist commentary. Corbucci treats The Great Silence as a sort of allegory for the failed student riots and demonstrations that occurred in Rome in 1967 and 1968. In the following decade this is the role, the function, that the Western genre would play. Marking the genesis of the revisionist Western.