Peter Watkins made a career out of deconstructing genres, employing reflexive tactics, advocating a freer media, and reinterpreting film language with a number of groundbreaking and epically experimental films. In 1992, Watkins offered a production course at the Nordens Folk High School at Biskops-Arno, Sweden. In this course, students directed, produced, photographed, built sets, ran lights, designed costumes and just about everything else to realize Watkins’ screenplay on the life of August Strindberg, The Freethinker. Stylistically, The Freethinker is a continuance of the themes and tactics Watkins first pioneered with his film Edvard Munch (1974). But The Freethinker is much more personal than a simple school project or stylistic exercise may seem. To Watkins, it was a platform from which to advocate a more intelligent and alternative form of Television programming.

The Freethinker centers around the life of dramatist August Strindberg, telling his story in a non-linear mode designed to undermine the usual processes by which an audience interprets a film. Strindberg’s story is told with reenactments, archival photographs, title cards bearing excerpts from his work, and contextual scenes of the same diversity pertaining to the every day living of Stockholm as well as its history. Cutting from archival photographs to actors playing the subjects of these photographs, Watkins links the actual history inexplicably with the “dramatic” re-created, or invented history authored by the filmmakers. Archival materials and scripted scenes sit side by side, creating a new filmic language of living history. The accuracy and authenticity of this vision derives from the scope of the vision itself. Between Watkins and his students, there are twenty-seven filmmakers expressing the same vision of this “dramatic” history, far more than those visions that commonly direct most mainstream filmmaking efforts.

There are two kinds of invented scenes. The first is entirely dramatic. This sort consists of a number of actors acting out their parts together in a scripted scene. The second is more akin to a documentary. In these scenes, an actor in character is “interviewed”, bearing witness to a number of historic and personal events.

There are other scenes when an actor appears in costume, but does not assume their role. Instead, they discuss their character, addressing the camera. These scenes, along with the title cards, present the audience with the greatest abundance of historic fact.

The second major text of The Freethinker involves Peter Watkins himself, allowing his concerns over media manipulation and control to come to the forefront of the film. The Freethinker departs from the re-created world of Strindberg, entering the year 1993, when the production itself took place. The segue to 1993 comes from a juxtaposition of shots between the reenacted debates of the Young Sweden and the lectures of Peter Watkins. While the members of Young Sweden advocate a disbursement of power to include the working class, Watkins calls for a disbursement in media control. Like the Sweden of the 19thcentury, the world of the 20thcentury suffers from the debilitating problem of only a few select and wealthy individuals controlling the power of the people. In contemporary terms, the media is absolute power; controlling knowledge, perspective and our shared experience of history. To employ socialist mechanisms upon these circumstances is precisely the objective of Watkins and Strindberg.

This relationship does not exist as juxtaposition alone. The players cast as the various members of the Young Sweden reappear, interacting, on what is quite obviously a set, with Watkins and his fellow filmmakers. Both parties engage in a debate, probing for a means to rectify the contemporary issues of media manipulation and control. Watkins and company come to the conclusion that a new media based vernacular or medium must be invented to bypass the moguls who control the international media. Title cards interject, each with an excerpt from a like-minded essay by Watkins. These essays in turn introduce the segment of the film dedicated to Strindberg’s piece The Swedish People.

In The Swedish People, Strindberg re-writes Swedish history, or, in a modern context, writes the first history of the Swedish working class. Strindberg reinvents history, Watkins reinvents media with history. This is the paradox at the heart of The Freethinker.

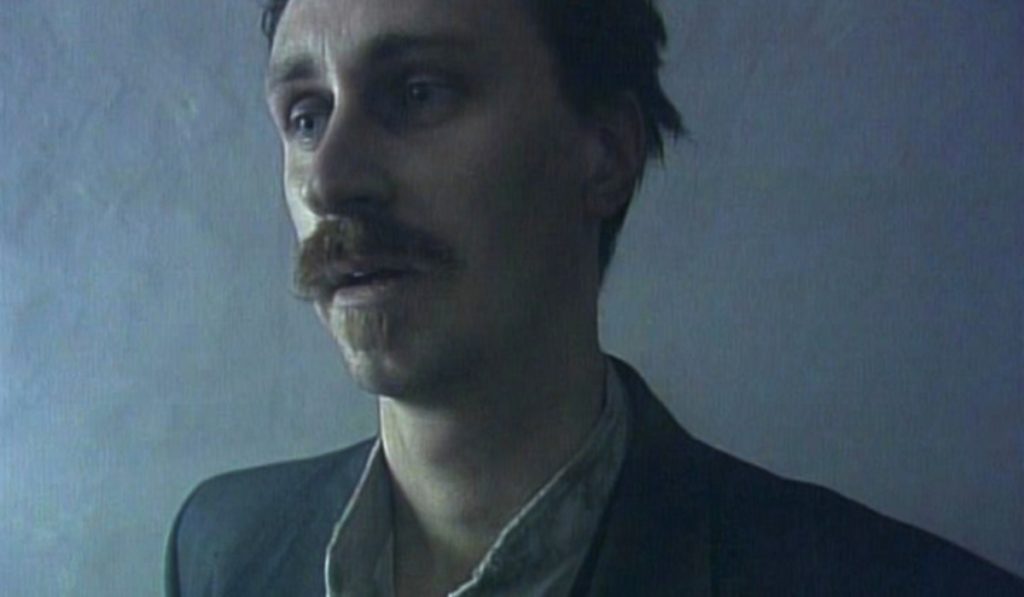

To examine contemporary media issues, Watkins is employing the life story and career of August Strindberg. To do this, Strindberg’s life story must be told, and his decisions examined for both their sociopolitical and personal ramifications. The paradox of The Freethinker comes to a head in a scene where Anders Mattson in character asStrindberg engages in a heated debate with one of the filmmakers on the issue of his child raising. Here, the investigative nature of this kind of filmmaking is dramatized literally. In response to the filmmaker, Strindberg questions the validity of posing personal questions pertaining to his marriage to Siri von Essen by redirecting the question to the filmmaker-“Have you ever been unfaithful to your wife?” The filmmaker’s response is that the film is not about himself, but August Strindberg. This brief moment in the film articulates the relevancy of a subject in regards to the placement of that subjects investigation; either in retrospect or in anticipation of. More significantly, the audience must contend with the matter if whether or not such personal information is vital to the narrative of the film or the history they are experiencing. Watkins believes it is, so the point becomes that only with an informed hindsight can one accurately judge the relevancy of various details to the historical significance of a subject’s life.

Watkins correlates the section of the film mentioned above with a segment on Strindberg’s autobiography The Son Of A Servant. While Strindberg outlines the misery of his youth and the abuse suffered at the hands of his father, the filmmakers inquire as to why Strindberg’s depictions are so black and white as well as being overtly melodramatic. Strindberg defends his work, arguing that The Son Of The Servan tis the story of his own developing mind. So, at Watkins points out, the only trust worthy account of Strindberg’s youth comes from Strindberg himself, and it is a highly subjective account. This is problematic; the question of validity and interpretive histories again resurfaces. Are the objective facts as equally important as the subjective memory of those facts? Watkins cannot interview the real August Strindberg, so he is left with no means to resolve the issue in this context. What Watkins does instead is return to the argumentative scene between one of his student filmmakers and Strindberg. The footage here is taken from a latter moment of that footage. Now both Strindberg and Watkins’ student have raised their voices, airing their frustrations at this debacle with harsh words. Unable to resolve the question he himself poses, Watkins again finds a literal representation of that conflict within the context of the film.

At this point in The Freethinker, it becomes clear that the major supporting player is indeed Siri von Essen (Lena Settervall). Siri von Essen receives the same overall treatment as her husband in the film; Settervall addresses the camera, acts out scenes, and reads from von Essen’s letters. What is quietly remarkable about the scenes she acts out is the natural nuance in them. Strindberg’s commentary comes later in the film to correspond with the subject of his book The Defence Of A Fool. However, in earlier scenes, information regarding the couple’s relationship is conveyed visually in scenes without diegetic sound or dialogue. These scenes rely on the actor’s ability to imbue their characters with a natural familiarity, intimacy and romance. The success of these scenes is telling of another stylistic approach to filmmaking that the film’s authors appear fluent in. These scenes are neither reflexive nor confrontational, working with the mechanisms of a more traditional narrative style instead. This tactic makes von Essen sympathetic very early on, despite the fact that her husband is so much at the forefront of The Freethinker. When their relationship comes undone during The Defence Of A Fool segment, both perspectives are clear and easily understood by the audience without coloring the characters black and white. The preservation of their multi-dimensionality is meticulously preserved in the editing of the film.

In the carefully constructed tableaux of The Freethinker, Watkins provides not just a context, a psychological portrait or a message, but is able to reflect both his and Strindberg’s desire for new forms in the media by employing numerous tactics, and in the process, inventing a new cinematic vernacular. Navigating Brechtian themes and reflexive tendencies, this film is as much a biography of August Strindberg as it is an essay on the importance of a new media. In the context of the film, Peter Watkins and his subject become synonymous.