Walter Hill has said that every film he’s made has been a western. I find it hard to argue with him on that score. Each film Hill has made carries with it some aspect of that mythology. Hill’s ability to bend and reshape genres is perhaps why he’s enjoyed a reputation as the “thinking man’s” director of adventure flicks. Those of us old enough to remember will undoubtedly recall all of the times that Quentin Tarantino sung Hill’s praises during the promotion of Reservoir Dogs (1992). Looking back on Tarantino’s career since then, it seems as though he really just wanted to be Walter Hill or at least make Walter Hill pictures.

Probably the most quintessential Walter Hill film is Streets Of Fire (1984). In roughly ninety minutes Hill fuses aspects of the western, the 1950s biker film, Blade Runner, and MTV music videos into one fast paced, adrenaline pumping “Rock n’ Roll Fable”. So why isn’t Streets of Fire as popular as say The Warriors (1979)?

Streets Of Fire is the cult classic for film cultists, the diamond in the rough that only a certain breed of cinephile knows about. One has to assume that a big part of this relative obscurity has to do with the fact that Streets of Fire is many kinds of movie at once (probably too many for most).

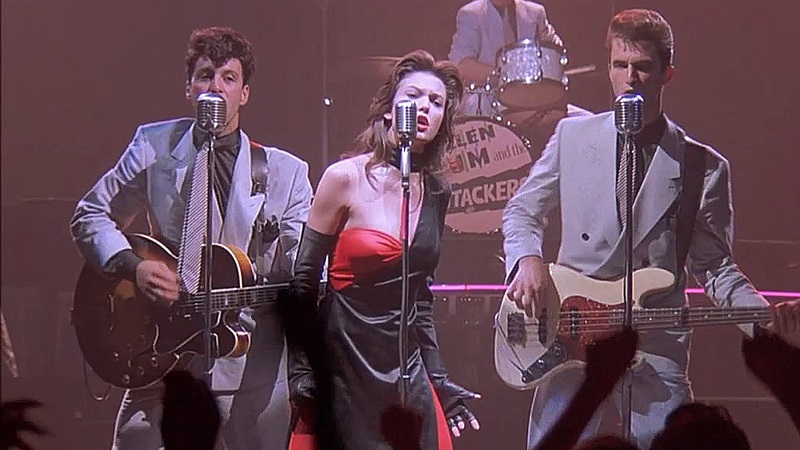

Set in “another time, another place”, Streets Of Fire is both past and present at once. The general population of the world in this film seems as though they were plucked right out of The Wild One (1953). The Bombers appear to be cast-offs from Mad Max (1979) while the police department functions more along the lines of a sheriff and his faithful deputy out of a Howard Hawks or John Ford western. The hero of Streets Of Fire, Tom Cody (Michael Paré), is part Robert Mitchum and part Warren Oates just as Ellen Aim (Diane Lane) is both Bonnie Tyler and Ava Gardner rolled into one. Add to all of these archetypes and signifiers the fact that the physical spaces of Streets Of Fire seem to be born out of the same cyberpunk milieu as Blade Runner (1982) and you’re faced with the most concentrated postmodern adventure film since Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981).

Hill’s whole approach to this aesthetic cornucopia is not dissimilar to the directing style of Sam Fuller; it is punchy, direct, and very fast. Everything, no matter how absurd, is taken seriously by Hill. This is why so much of what is potentially outlandish in Streets Of Fire works and feels earnest. Even the transitions into the sequences that are essentially “mini-music videos” within the film feel a part of the natural impulse of the film. These musical elements give the film an effective means of exploring emotional subtext without breaking the fast paced edits or the titillating spectacles or beautiful boys and girls rain soaked and bathed in neon lights.

The purpose of all of this is truly just a celebration of cinema. Streets Of Fire isn’t the kind of cinematic celebration one would associate with Jacques Rivette or anything; this is pure Walter Hill. Streets Of Fire is a celebration of the potential of the cinema to create explosive new dreams and fantasies. This is the cinema of youth, the teenaged years of angst, rebellion, and larger than life ambitions. Anyone who has grown emotionally with the cinema or was invested in the moving image enough to even grow because of the cinema; Streets Of Fire is the film that celebrates you.