In Ardmore, not far from the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, is a video store called Viva Video: The Last Picture Store. This is one of the last proper video stores in the Philadelphia area and, in my opinion, the best. They have an extensive collection of films which run at excellent rates. What’s really appealing about Viva Video is that they have a variety of Region 0 releases in both BluRay and DVD formats that represent titles that aren’t so easy to come by except for sale on Amazon.

My first rental from Viva Video was the boxed set from Film Movement of Ernst Marischka’s Sissi films (this set counted as a one title rental). Film Movement’s presentation of these three films is gorgeously done with a new 2k restoration. The supplements may not have been as incredible but they were still insightful enough for me to recommend to viewers that they check them out. But all of this babble about presentation and special features is beside the point. What matters is the films themselves.

Marischka’s trilogy of films about the life of Empress Elisabeth of Austria (known as Sissi to her family and friends) represents less the 19th century and more the mid-twentieth century as Austria rebuilds itself in the wake of WWII. The Romantic treatment of the material coupled with moments reminiscent of travelogues and the numerous historical omissions on the part of Marischka indicate a need to return to a period of a country’s history that the national consciousness of that moment finds both affirming, uniting, and idyllic.

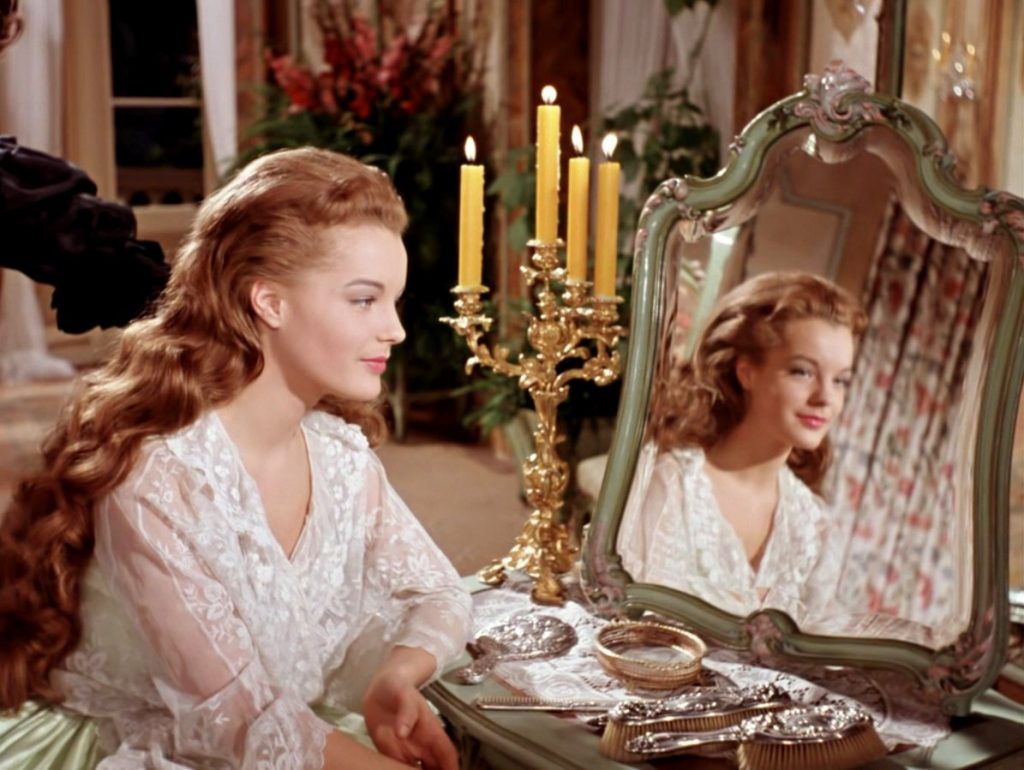

In Sissi (1955), Sissi die Junge Kaiserin (1956), and Sissi – Schicksalsjahre einer Kaiserin (1957) Ernst Marischka uses the same basic narrative formula. Each film features a plot regarding Sissi’s anxieties regarding marriage in the foreground with a broader political issue looming in the background. Once Sissi overcomes her anxieties and personal conflicts she is able to, with her charm alone, settle all political disharmony. This formula depicts Sissi as a kind of Germanic idealization of femininity. She is at once naive and girlish while also being perceptive, charming, and forthright. The duality to the Sissi character is echoed visually as well, most dynamically in Sissi. She is first introduced at her family seat in Bavaria wearing a relatively plain dress while caring for a deer whom she has adopted. This visual serves as a kind of icon that is drawn from classic Eastern European folklore where virtue is tied to the forest and its inhabitants. Later, however, Sissi is framed in wide shots that privilege her body and gowns over setting, almost as if she had ascended from the earth to the heavens (which in this case is the Viennese Court).

In terms of genre the Sissi films are a mix of historical epic and women’s melodrama (aka “weepy”) whose structure and overall design (from editing to sets) are set in the Hollywood tradition. Bruno Mondi’s cinematography immediately invites comparisons with Victor Fleming’s Gone With The Wind (1939). This comparison isn’t all too surprising considering the parallels between Austria in the 1950s and the United States in the 1930s. The nostalgia and sentimentality which permeates every frame of the Sissi films could also be easily tied to the participation of the Ufa in the production. This correlation in the Sissi films between escapism and the historical epic seems even more relevant given such contemporary television programs as The Crown and Victoria which offer a kind of retreat for Trump-era audiences into the opulence of Court life and the world of the Royals. The type of escapism that the Sissi films represents, with their grandeur and sentimentality, certainly accounts for the sustained popularity of these films. According to the special features Film Movement provides on this release the Sissi films are a popular Christmas tradition in Europe (Empress Elisabeth was actually born on Christmas day).

The Sissi films are equally indebted to other far more German styles and genres. In the second Sissi film, Sissi die Junge Kaiserin, there is an entire sequence born out of the once very popular Bergfilm that made celebrities of Dr. Arnold Fanck and Leni Riefenstahl. Equally important is the effect that the “German Griffith” Ernst Lubitsch has had on the humanizing of historical dramas. The Lubitsch sensibility can be felt in the light way that Marischka choreographs the various scenes of romantic intrigue between Sissi and Franz. In effect Marischka has orchestrated the Sissi films to be a kind of ode not just to Austria but the very idea of a pan-German identity.

What will most likely draw American cinephiles to these three films though are the stars Romy Schneider and Karlheinz Böhm. Schneider is brilliantly cast as Sissi though she is probably more recognizable today for her roles in Orson Welles’ The Trial (1962), Clive Donner’s What’s New Pussycat? (1965), and Andrzej Zulawski’s The Most Important Thing: Love (1975). In each of these roles is an element of the character Sissi whom Schneider could never really be able to separate herself from. In fact, when Luchino Visconti made his film Ludwig (1973) he cast Schneider once again as Empress Elisabeth. Karlheinz Böhm, on the other hand, was never pigeonholed by his role in the Sissi films the way Romy Schneider was. Böhm’s career was more deeply affected by his role in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960); though there is an aristocratic quality to Böhm’s characters in the Rainer Werner Fassbinder films Martha (1974), Effi Briest (1974), Fox And His Friends (1975), and Mother Kusters Goes To Heaven (1975) that certainly derives from the character of the Emperor of Austria.

Even if one isn’t familiar with Romy Schneider, Karlheinz Böhm, or European Cinema the Sissi films are likely to be an enjoyable escape. These films are much like Sissi herself in that they are very charming. If one can see the Film Movement release then one gets the added pleasure of the 2k restoration which does tremendous justice to the color cinematography.