It’s not all that surprising that in the mid-eighties brothers Lawrence and Mark Kasdan would write a western about family values. Silverado (1985) is one of the better known westerns of that decade with an all-star cast and a major budget. But unlike contemporary westerns like Walter Hill’s The Long Riders (1980), Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) and Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider (1985), Silverado turns its back on the legacy of the revisionist western in favor of a more sentimental view of the old west; one that recalls the latter films of John Ford and Howard Hawks. Silverado may look as authentic as The Long Riders or Heaven’s Gate but it feels like a family picture.

Silverado is about a group of misfits (Scott Glenn, Kevin Kline, Danny Glover and Kevin Kostner) in search of familial connections who all end up in the titular frontier town where they face-off with a corrupt sheriff (Brian Dennehy). During their misadventures they encounter a noble salt-of-the-earth settler (Rosanna Arquette), a flashy gambler (Jeff Goldblum), and a wise saloon keeper (Linda Hunt); each of which serves as a kind of reflection of an idealized existence according to each of the protagonists. Lawrence Kasdan directs his ensemble much the same way as he did The Big Chill (1983), emphasizing those moments where characters just sort of “hangout”.

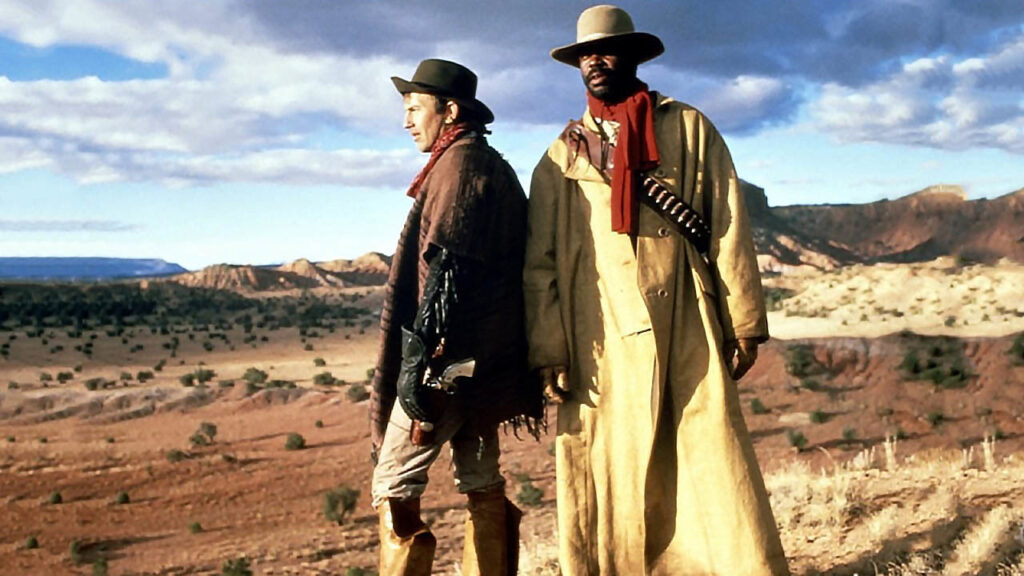

Each lead is an archetype and his individual arc follows a familiar path. The gunslinger brothers (Glenn and Costner) must protect their kin from the violence of corruption while Danny Glover’s prodigal son stands up against systemic oppression and Kevin Kline’s reformed outlaw learns to plant roots by usurping the bad guy. Either literally or figuratively these arcs find the protagonists ensconced with some form of family.

Silverado, with its small insular local, doesn’t permit complex narrative interconnections. Silverado, in terms of its writing, mirrors the sophistication of Kasdan’s scripts for the Star Wars films wherein characterization only occurs when there is a certain chemistry between performers. The more charismatic leads of Glover and Kline feel the most distinguished not because of the writing but because of how they play off of their respective scene partners. Kline has more to do in the dialogue department but Glover gets all of the iconic framing that lends gravitas easily to the legendary performer.

One of the oddest things about Silverado is the Rosanna Arquette character who is set up to be Kline’s love interest, then Glenn’s and then just sort of fades from view. In the episode of the narrative where Arquette is introduced she doesn’t even speak. Kasdan gives Arquette lingering close-ups with nothing to say. Within the dramatic economy of Silverado the only women with any agency are surrogate mothers (like Hunt) or sisters. Women who are uninitiated to the family unit exist either as the promise of an honest life or a good time. Arquette represents the former; she is ever stoic, chaste, and dull.

Lawrence Kasdan has always been more of a writer than a director. Kasdan’s Wyatt Earp (1994) is likely one of the least cinematic westerns ever made and makes Silverado look downright revolutionary. Visually, the sequence in Silverado that stands out is the opening scene where Glenn guns down a gang of hired killers. It is a rapidly cut, claustrophobic scene of violence that is completely condensed à la Fritz Lang’s Rancho Notorious (1952). Silverado opens with bravura but it ends with a whimper. The film concludes with a shootout between Kline and larger than life Dennehy that has none of the pre-requisite urgency befitting the genre.