Derek Jarman’s first feature, co-directed by Paul Humfress, was released in 1976 with the rating “X”. The film was Sebastiane, and it told the story of St. Sebastiane’s martyrdom in the days of early Christianity. This film is unique in Jarman’s filmography. Unlike his work that proceeded it, Sebatiane is relatively void of fantastic color schemes and postmodern metaphor. All these components are evident in Sebatiane, but with a restraint absent in Jarman’s later films. Sebastiane has more overtly in common with the early films of Pasolini rather than with Jarman’s own work.

Like The Gospel According To Saint Matthew by Pasolini, Sebastiane’s scenes are episodic, sparse in image composition and dialogue, and heavily reliant upon the minimalist devices of Italian neo-realism. Interestingly, Derek Jarman and Pier Paolo Pasolini are hardly dissimilar as individuals. Both men were openly homosexual, had studied painting, and began their careers working on other director’s films (Pasolini with Fellini, Jarman with Ken Russell). Such similarities may explain the overlap in cinematic style, or nothing more than the influence the elder filmmaker had upon the younger (Pasolini was murdered in 1975).

In the opening scenes of Sebastiane, based in Rome, Jarman transposes the court of the Caesar into the decadent bordellos of swinging London, with a passion for moral corruption likewise evidenced in Pasolini’s own Arabian Nights. The similarities Jarman draws between the classical and contemporary signifies the ever-present issue of political and sexual depravity among the wealthy and powerful. He likens the British upper classes, the politically ambitious, to the dangerously self indulgent Roman society.

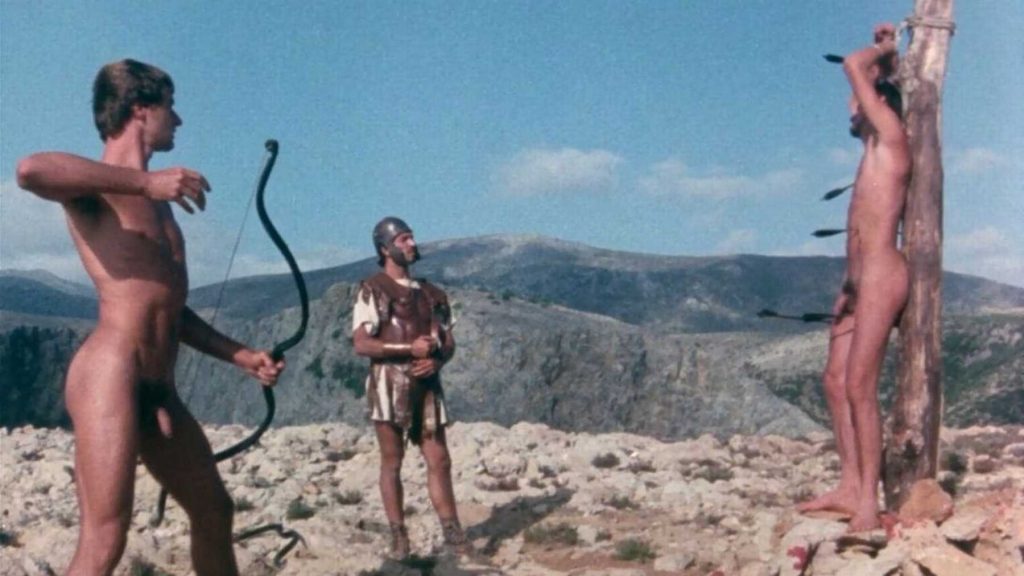

The film then shifts its focus to the penal colony where St. Sebastiane is condemned. Here the splash and vigor of Rome dissipates into quiet scenes of torture and homoerotic beauty, both perpetrated by the Roman guards. For a Derek Jarman film, the political subtext of these sequences is comparatively subtle. Jarman seems concerned with the relegation of homosexuality in western civilization to the margins; in this case the obscure wilderness of unconquered ancient lands. The successful suppression of homosexuality by the Romans is therefore, given the narrative, synonymous with the suppression of Christianity. Linking the two this way may seem contradictory, but that is intentional. Derek Jarman relates the two as victims linked by their oppression.

All of these formalist trappings and subtexts are subject to oversight given Jarman’s own wild attention to detail, that also healthily juxtaposes the early sequences in Rome. The detail I speak of is Jarman’s decision to shoot the entire film in Latin, the language of the Roman World (another little nugget of information is that this film featured Brian Eno’s first original music score). Sebastiane has the unique distinction of being the only feature film shot entirely in Latin. This choice gives additional weight to the scenes of violent realism, primarily consisting of torture, that heighten the contrast of the fantastical sequences of sexual pleasure in the desert and of the Roman banquet at the films beginning.

For a debut feature filmmaker, even for one working with a co-director (similar to Nicolas Roeg’s debut Performance), Jarman is evidently more than capable of creating a successfully complex and engaging film. Sebastiane is a remarkable debut film that skillfully and tastefully acknowledges its debt to Pasolini as well as establishes Jarman’s own painterly flare for composition and theatricality in his depictions of both the sexual and the political.