“For at least two years I have felt ready to make some theoretical statements about film language in relation to the ‘Underground’ film. A problem which has held me up is the discrepancy I feel between the actual experience I get from film making and viewing – the erraticness, impulsiveness and irrationality – and the linear logic that emerges from writing about it. The clarity of a verbal statement creates a misleading feeling of having understood or stablished a set of experiences or phenomena, and one is tempted to let it substitute for the less conveniently comprehended physicality of image-experience.”-Malcolm LeGrice, 1972

Writing about the cinema in the last couple of years has become increasingly difficult. When I first began writing about films in a pseudo-professional capacity for CIP late in 2011 the cinema seemed to be a succinct and easily definable medium. In part this was due to the assignments I had been receiving (usually a retrospective analysis of a “classic” French film), but also the fact that when I had begun writing about the cinema I had just graduated from college. It was in college, particularly in classes dealing with film history, that the cinema was presented as a broad yet recognizable category of Fine Art that contained within it a series of easily categorizable elements, labels, and genres. This limiting view of the cinema was the gospel, reiterated time and again as a dirge of propaganda.

A year after college and six months into working for CIP some real perspective began to accumulate. As I continued to make film after film it became increasingly evident that there is a fluidity to the cinema. One cannot make a film that is exclusively one way or another, nor can one limit one’s self to a singular reading of a film. Every film is unique in its way; a link in the chain of the career of its author, be it the director, producer, writer, cinematographer, etc. What’s problematic is that after such a realization that fundamentally redefines one’s notions of the cinema, this realization has a rippling effect. As one trains one’s mind to interpret and invent the cinema, one begins to find the cinema in places where one was instructed it simply did not exist when one was in college. Of course I am referring to web-series, American Television, pop-up installations, fan made photo montages of celebrities on YouTube, etc. Just as technology permeates every aspect of human existence, so the cinema permeates every aspect of technological existence. In the last five years the fluidity of the cinema, which struck me as so profound several years ago, has doubled. The adaptability of the cinema, along with its accessibility, appears to be an expansive force, a global tidal wave crashing over human culture in a rhythm, successive yet sustained.

In a media environment where labels are quickly becoming void of their original meaning a discussion of cinematic principles is becoming increasingly difficult. Almost out of necessity I’m tempted to ground the evolution of the cinema of the past fifty years in the context of one filmmaker’s career or another. Michael Snow would be, in my opinion, the best candidate for such a discussion if I were to go that route. Never as popular as he deserves to be, Michael Snow’s career charts, almost too perfectly, the modes of cinematic production and its evolution from the “Underground” films of the seventies to the multi-media and video installations of today. Snow’s voice and aesthetic interests have remained consistent, propelled into new technologies only by Snow’s sincere desire to create.

But to lead such a discussion with Michael Snow as its center piece would only be beneficial to those who have already immersed themselves in a cinema where narrative and the possibility for escapism are not requirements of the cinematographic langue. To most audiences the requirements of the cinema demand a fabricated reality, a fiction indebted to the conventions of literature. So the discussion must include filmmakers who have sought to de-arrange these popular principles of cinematic convention but who have also, even if only on a theoretical basis, pushed the cinema into uncharted avenues.

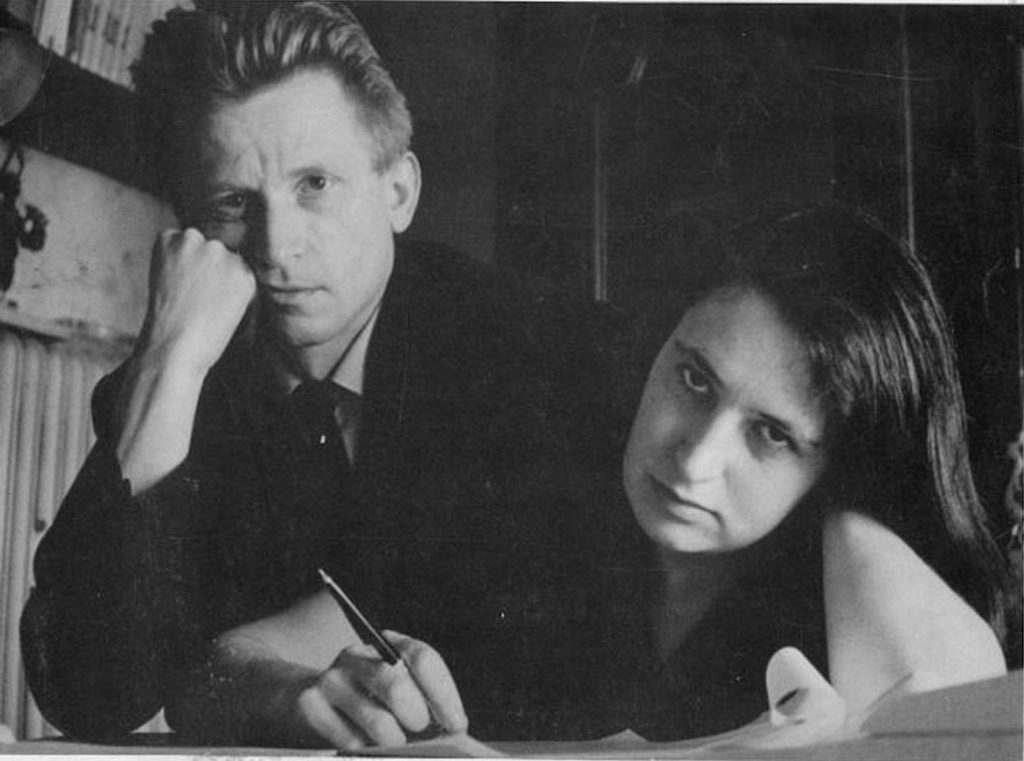

The best candidate to open this discussion, who is coincidently one of Michael Snow’s earliest champions, is Jean-Marie Straub. Born to the same generation as Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard, Straub’s career goes back to the fifties when he first began collaborating with his wife Danièle Huillet (1936-2006). Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s films, in a physical sense, are dominated by long static compositions with a minimalist approach to blocking and set design. Their films represent a distillation of the cinema to its primal elements. What makes this duo relevant is their consistency in their aesthetic approach that maintained their position as a truly unique force in world cinema for over forty years.

“this is really a film for children”-Danièle Huillet

It’s important to any analysis of European Cinema, especially German cinema, to bear in mind the tremendous influence Walter Benjamin had on the filmmakers who would originate the French and German New Waves of the sixties. Despite their birthplaces, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub have a distinctly German voice to their cinematic expressions; Straub himself was a mentor to Rainer Werner Fassbinder after all. But in the interest of space and time, it would, perhaps, be helpful to turn to critic/filmmaker Alexander Kluge for an astute summation of the aesthetic principles that he, as well as Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, aspired to.

“A very easy method would be for the audience to stick to the individual shots, to whatever they happen to be seeing at any given moment. They must watch closely. Then they can happily forget, because their imagination does all the rest. Only someone who doesn’t relax, who is all tensed up, who searches for a leitmotif, or is always finding links with the ‘cultural heritage’, will have difficulties. He’s not watching closely anymore. What he sees is semi-abstract and not concrete. It would be a help if he quietly recites to himself what he hears and sees. If he does that it won’t be long before he notices the sense of the succession of shots. That way he’ll learn how to deal with himself and his own impressions.” (Film Comment, Vol. 10, no. 6, 1974)

What Kluge proposes Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub realized in their films. As I stated earlier, the physical attributes of their work correspond to Kluge’s proposed distillation of cinematic expression. If one examines one of their later works, Sicilia! (1999), one is struck by how little the film explains with regards to the underlying narrative purpose of the film. The scenes simply “exist”, and it is in their chronological alignment that meaning can be found. As with Kluge, this meaning must be manufactured by the audience. Wrongfully, this approach to narrative cinema is typically referred to as “too intelligent” primarily because a film such as Sicilia! depends so much upon the participation of its audience.

This cinematic model of distillation is similarly at work in Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa Vie (1962). However, Godard minimizes the involvement of his audience by inserting title cards between each of the scenes or vignettes in Vivre sa Vie. These title cards, like the chapters in a novel, explain to a minimal degree what it is that the audience is about to see happen, thus allowing the audience to concentrate its attention on the more superficial elements of the film. Without these title cards Vivre sa Vie would have the effect of Sicillia! or Moses & Aron (1975). Even more commercial filmmakers, like Rainer Werner Fassbinder, adopted the Kluge/Straub/Huillet approach only to minimize audience participation in different ways. Fassbinder’s Beware Of A Holy Whore (1971) relieves the audience of some responsibility through the direction of its actors and its fluid cinematography. The effect of this is Brechtian, thus recognizable and easily contextualized.

This approach to the cinematographic langue is not, by any means, an effort restricted to the generation of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. Their influence strongly colored Chantal Akerman’s early narrative efforts Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978). Likewise, Hal Hartley makes use of this aesthetic approach significantly, and rather subtly, in his film Henry Fool (1998). It is at the core of this aesthetic that the audience must, to a degree, join the filmmaker in authoring the film itself. In contrary to the belief that such a mode of cinematic expression is “too intelligent”, these films, and this style in particular, remain one of the most accessible of the cinema. So much so that Danièle Huillet, in the first issue of the British film magazine Enthusiasm, once observed that her film with Jean-Marie Straub, Not Reconciled (1965) was “really a film for children”.

“all art may be seen as a mode of proof”-Susan Sontag

In the Summer/Autumn issue of Moviegoer published in 1964, Susan Sontag outlined the aesthetic impact of Godard’s Vivre sa Vie. It’s safe to say that at this point America was unaware of Alexander Kluge, Danièle Huillet, and Jean-Marie Straub. Regardless, Sontag pinpoints their desired cinematic intent and puts it very succinctly when she terms it “proof”; a cinema of proof. By contrast, all other commercial cinema not conforming to the aesthetics proposed by Kluge and Sontag belong to the cinema of analysis (“analysis” is the word Sontag chose as the opposite of “proof” in her article).

A cinema of proof today seems almost impossible. Consider the period critics refer to as the Second French New Wave (1978-1984). Filmmakers Alain Resnais, Eric Rohmer and Jean-Luc Godard are finding renewed commercial success with their films, films that have remained as provocative and innovative as Breathless (1960) was many years before. Godard, the most internationally marketable filmmaker of the three, found his success short-lived in the market of the “blockbuster spectacle” when he released Passion (1982). Passion, despite its self, remains one of the finest examples of what we have in this essay been terming the cinema of proof. It’s a film that employs the tactics of Straub and Huillet with the wit to dissociate the audience from the would-be protagonist (played by Hanna Schygulla) and re-associate them with the director (played by Jerzy Radziwilowicz) by means of a shared experience (audience contribution equated with traditional film authorship). In this way Godard’s Passion succeeds where Michelangelo Antonioni’s Identification of A Woman (1982) stumbles. Still, neither film found any success beyond the critics and champions of these filmmakers.

Consider now that a cultural environment existed in the sixties and seventies that allowed a cinema of proof to flourish, and compare those conditions with the needs audiences tax upon their different forms of media today. A cinema of proof would be impossible. If the sixties were Godard’s golden period (in terms of success) then the 2010s would be the age for Luc Moullet’s drastic reappraisal.

“illness always has a few beneficial side effects”-Gilles Taurand

From today’s perspective the idea of a cinema of proof seems an almost Romantic notion. I’ve read that Jean-Marie Straub considered his films (and thusly those films that follow the same aesthetic guidelines) to be “eternal” in both their simplicity and accessibility. His notions, however, are dependent on an audience willing to invest what Kluge fondly referred to as their “imagination” into the film viewing process. In 2015 technology along with the speed of daily life prohibits that kind of investment, relegating this would-be utopian cinema to a kind of touchstone by which to asses the success of other films in incorporating the audience into an intellectual dialogue.

Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers (2009) utilizes Straub’s aesthetic in literal terms but its sheer gross-out spectacle leaves little room for the imagination. Similarly, the films of Andrea Arnold come close to this but always back off to safer narrative convention in the third act, as if the climax of her films would be too difficult for audiences otherwise. The distillation championed by Straub could still find renewal in a form of new technology, in which case an entire reassessment of aesthetic models would be mandatory in order to better calibrate the juxtaposition between manufactured image and spectator. What Straub gives us today is a kind of looking-glass through which cinema may be measured and accounted for in certain areas.