Author Jun’ichirō Tanizaki and director Yasuzo Masumura were frequent collaborators in a sense; the latter making a number of films based on the former’s novels, many of which deal with either masculine wounded pride or directly subvert the traditionally male roles in Japanese society. Masumura’s modernist style lend these films a cartoonish humor that serves to give the audience a sort of Brechtian distance from the narrative that is not dissimilar to the works of Frank Tashlin and Joe Dante. Love For An Idiot (1967) fits within this canon of films but is an even crueler indictment of masculine tradition.

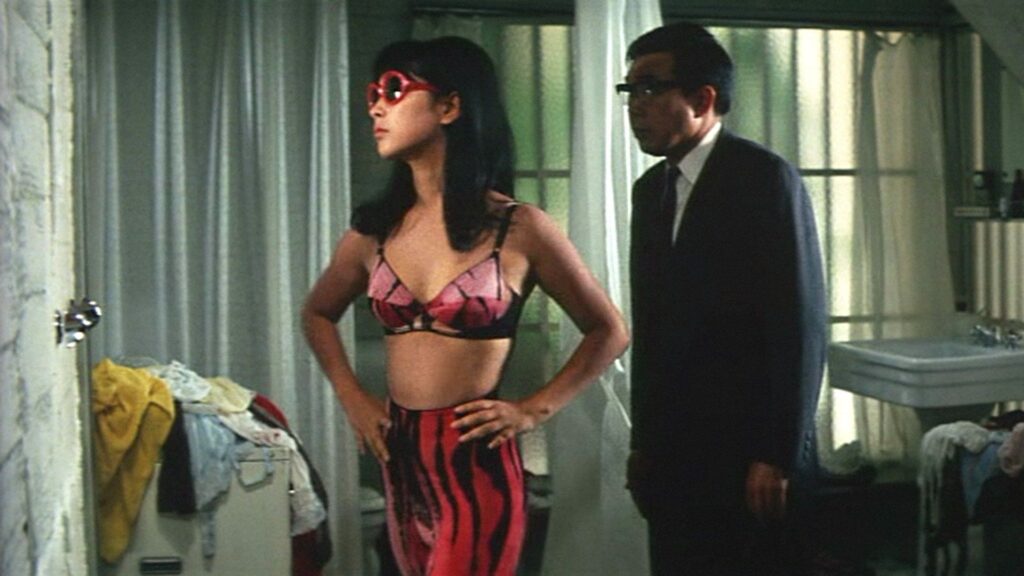

The novel Naomi (the source for Love For An Idiot) essentially follows George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion in terms of dramatic beats for the first half but then turns on itself in the second half. Love For An Idiot follows the same structure except that Masumura’s direction, particularly of the actors, grows increasingly manic. Into this complex Masumura also interjects his love of images lifted from popular culture. In Giants & Toys (1958) advertisements dominated this aspect of his aesthetic while in Love For An Idiot it is the pin-up which rules. This gesture towards capitalism and its vast amounts of disposable images only further commodifies the character of Naomi (Michiyo Ookusu) within her relationship to Jōji (Shōichi Ozawa).

At first it is Jōji who dominates Naomi and is steering her on a path of his choosing as per their arrangement. However her various infidelities prompts the two to part at which point Jōji experiences a sort of nervous breakdown. When she returns to gather her belongings it is Jōji who submits completely to Naomi’s will. In the process of submitting to Naomi, Jōji forsakes all of the masculine principles which have defined his life thus far.

But a kind of flexible dom/sub dichotomy was always present in the relationship between Naomi and Jōji as evidenced by their role play. Masumura seizes on this concept of course and stages their role play as a frantic bit where Naomi rides on Jōji’s back like a pony while spanking his behind. Scenes like these balance to montages of pin-up style photographs which Jōji ogles like Bugs Bunny beholding a giant carrot. Even when Masumura stages these escapades humorously he never judges these characters based upon their desires. It’s a fine line to walk but Masumura pulls it off quite well.

The concerns that reoccur throughout Masumura’s oeuvre point a man bewitched by the transformations that his culture underwent in the post war years. A general distrust of capitalism specifically becomes one of the unifying themes. Even in Love For An Idiot Masumura addresses capitalism in the guise of how Jōji gazes at Naomi. But he also makes room for further scrutiny in the scenes where Jōji is at work at what appears to be a chemical processing plant. Scenes at this location, no matter how brief, are always prefaced with a series of static shots pipes, knobs, wires, and other objects of advanced industrialization. Capitalism brings modernism which in turn morphs the very landscape of Japan.

Love For An Idiot, as one may well guess from the title, fits more in the vein of Masumura’s comedies than his dramas. While the ideologies on display in all of Masumura’s films is relatively constant, his styles between comedy and drama differ immensely. The Black Report (1963) and Blind Beast (1969) imagine modern society as totally unrelenting and unforgiving in its charge towards the 21st century. Masumura’s comedies, on the other hand, focus more on the adaptability of individuals like Naomi and Jōji, finding redemption in their commitment to singular ideas such as marriage.