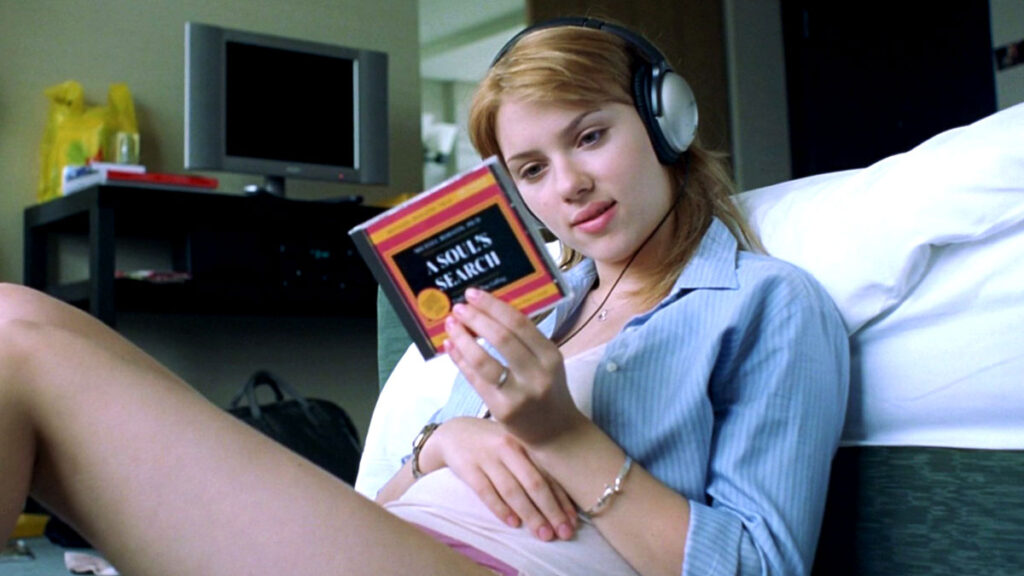

How perfect is it that a film which so defined a generation should open with a shot of Scarlett Johansson’s buttocks? Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation (2003) is one of those films that came out at the precise moment where it captured the zeitgeist. Johansson’s character Charlotte epitomized a generation’s trepidation as they moved towards adulthood. Lost In Translation was as cathartic and instructive as it was reassuring. This film didn’t just make Johansson a star, it tied her inextricably as a kind of avatar for that generation.

Even though aspects of Lost In Translation have not aged well or are simply off-putting, it in no way diminishes the impact that the film had. Lost In Translation was only Sofia Coppola’s second feature and it managed to do all of this which is a career defining accomplishment. In many ways Coppola has never surpassed Lost In Translation with its subtle gestures and smoldering emotions. It is a powerful film where nothing really happens and yet that nothingness has more to say than a dozen The Bling Ring (2013).

Bob Harris (Bill Murray) is Bill Murray; the wise paternal sage that we all wish was our partner too. Harris is at a crisis point in middle age with regards to both his marriage and his career while Charlotte struggles to get her own life started in terms of her marriage and her own career. The pair is at different points in their journey but at the same crossroads when they meet in Tokyo. They are drawn to each other, each mentoring the other in different ways and each entranced by a possible romance that never occurs. The tension and camaraderie is palpable from the instant they first catch each other’s eye on an elevator. This unlikely bond is born out of loneliness which Coppola finds in the wide angled landscapes of the Tokyo metropolis.

This loneliness is most painfully apparent in the character of Charlotte. When she isn’t being told by her husband (Giovanni Ribisi) that she’s “snotty” he is ditching her to go pursue his career. It’s immediately clear that this couple is too young to have married. Charlotte, at least until she meets Bob Harris, is essentially trapped in a relationship that belittles her intelligence and stymies her ability to define herself; a scenario endemic too many people who marry too young.

Coppola is confident and mature in her selection of images, taking her time to paint a portrait of her leads before their friendship blossoms. The moments that are most important in Lost In Translation are the awkward smiles of embarrassment and indulgence from Charlotte or the confused, helpless looks of Bob Harris. So much more is communicated by what the camera observes rather than what is said or planned.

Coppola’s ex-husband, Spike Jonze, made a film ten years later, Her (2013), which also featured Johansson and is a kind of response to Lost In Translation. Unlike Lost In Translation, Her is about a self-pitying man whose single comfort comes in the form of an artificial female presence. In Jonze’s film the “good” women are automated and the “good” guys are helpless emotional parasites. As a rebuff to Coppola’s film Her never really succeeds. It does, however, make the merits of Coppola’s film all that more apparent.