Frankenhooker (1990) is one of the seminal genre films of the nineties. It’s a low budget horror-comedy riff on Mary Shelley’s novel that has become one of the most popular feminist texts in post-modern American cinema. Frankenhooker is a campy, cheesy, and grotesque satire of the commodification of the female body in culture. Though it’s been a staple of feminist discourse in the cinema for over thirty years, new political attacks on female bodily autonomy and agency have made Frankenhooker terrifyingly relevant in an all new way.

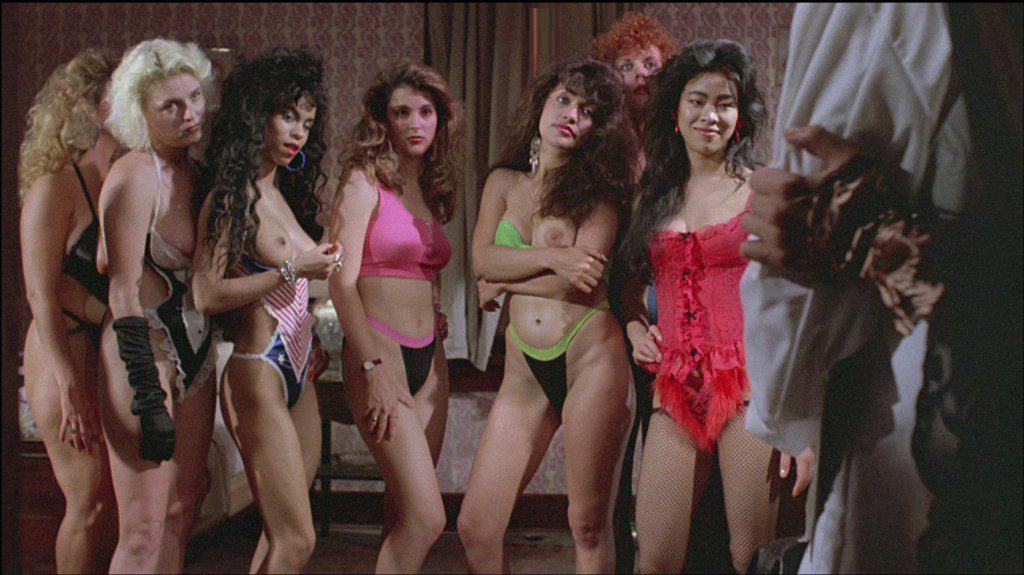

Frankenhooker could only have come from the brilliantly demented imagination of Frank Henenlotter, one of “shock” cinema’s great auteurs. Henenlotter’s long tenure as a cinephile based in New York’s Times Square (pre-gentrification) is essential to Frankenhooker‘s agenda. Beneath the slapstick, high camp, and general goofiness Frankenhooker argues for legalized prostitution and comes out against bodily commodification, drug addiction, and sexual slavery. The progressive political views of the filmmaker are served up in a comically gory fashion that subverts the genre norms.

Frankenhooker‘s relevancy today is clear, but from the perspective of the twenty-first century the ending doesn’t land so much as a gag (which appears to be the original intent), but as an indictment of heterosexual male paranoias. When amateur mad doctor Jeffrey (James Lorinz) finds that his re-animated girlfriend Elizabeth (Patty Mullen) has grafted his head onto a hodgepodge of female body parts he reacts in terror. For Jeffrey, who has spent the bulk of the movie trying to bring his girlfriend back to life after a fatal encounter with a lawn mower, this is an assassination of his heteronormative identity. His reaction of terror has come to represent the bigotry and fear that straight men, as a political institution, represent.

It’s important to note that the conditions that brought about this physical gender change are entirely of Jeffrey’s own making. His tools and entire process were designed specifically to re-animate dead female tissues; to save Jeffrey Elizabeth had to re-assign his physical gender. Frankenhooker is a film wholly ignorant of the notion that gender identity is not exclusively physical. In 1990, when the film was made, these concepts were not as widely known and therefore elude the filmmakers. Yet it manages to predict and effectively satirize the reactions of the political right to these ideas.

Perhaps this has something to do with the very nature of Mary Shelley’s novel and its many popular reiterations. Henenlotter’s Frankenhooker embraces the same conceit as James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) wherein the nature or personality of a being’s flesh is dictated by their own psychology. Where in Whale’s film the “monster” is murderous because his flesh comes from murderers, in Frankenhooker Elizabeth assumes the profession of the prostitute because her body is a collage of prostitutes. These abstract notions and traits are physically linked to the flesh so it is no stretch of the imagination to believe that Jeffrey’s own heterosexual male identity would assert itself on his new female form.

Frankenhooker‘s various assertions are all contingent upon a gender binary that allows for easy feminist readings and interpretations but stymies more contemporary gender philosophies. Frankenhooker is an essential feminist text in the horror genre that, despite the sociological limitations of its historical moment, bridges the gap from the aggressively gender binary films of its time to the more gender fluid films that followed some ten or twenty years later.