Last Friday I had tea with my buddy Neal to discuss programming a series of Czech New Wave films. Chatting away, two content cinephiles, the subject of Frank Perry came up. We both admire his work very much and determined that as far as we’re concerned he is an all too often overlooked filmmaker in film schools. I will examine my favorite film by Perry, The Swimmer, by way of a comparison to Perry’s debut film David & Lisa (both of which were also written by the director’s wife Eleanor Perry).

Released in 1962, David & Lisa tells the story of two young people who have voluntarily entered themselves into a home for psychiatric care. Lisa (Janet Margolin) develops a strange attraction to David (Keir Dullea) that can only be characterized as a crush.

Sadly, Lisa suffers from an extreme social disorder and is prone to violent outbursts and mood swings. David is far less afflicted. His social anxieties are those of any teenage boy, though they manifest themselves in a more dramatic way than one is accustomed to. While David has every chance to recover, Lisa does not. The relationship between the two forces David to become partly responsible for Lisa.

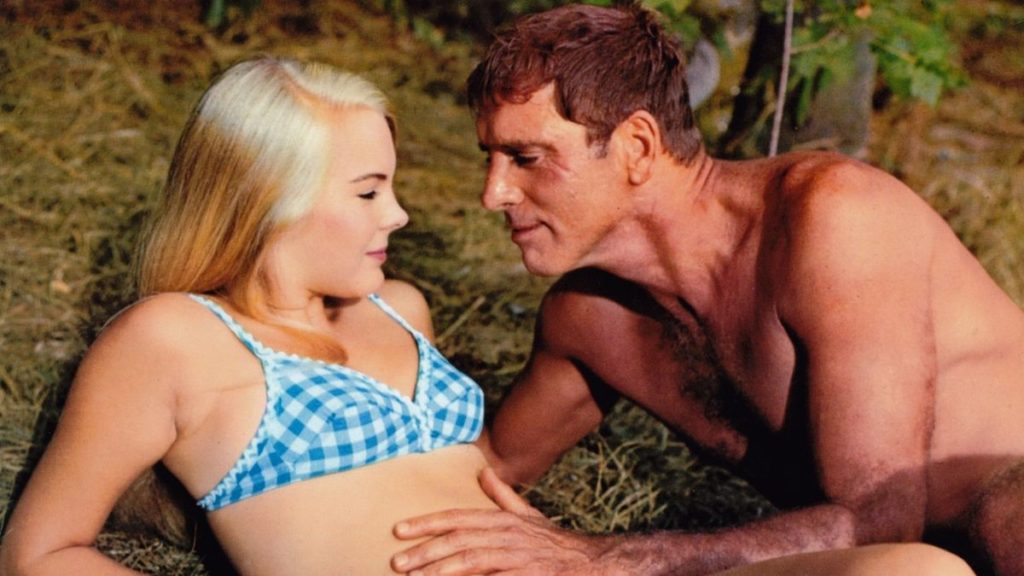

1968’s The Swimmer, from a story by John Cheever, tells of a different kind of social disorder. In David & Lisa, social disorders are externalized in scenes with a therapist (Howard Da Silva), where as in The Swimmer they remain internal and ambiguous to the audience. Ned Merrill (Burt Lancaster) sets out one late summer day to swim home across the county, going from pool to pool.

A confessed eccentric, what makes Ned’s story so tragic is the suppression of his emotions and the past that has fostered these feelings. With every neighbor he encounters, a little more of his life story is revealed to the audience and to himself, allowing him to emotionally unravel simultaneously while he physically unravels swimming across the county. In this way, the audience comes to relate to Ned very clearly, sharing his experience, articulating even the most nuanced of emotional patterns (Perry played with this tactic in David & Lisa in the scenes between David and the psychologist).

However, similarities in characterizations and the formalist tendencies at work extend beyond the parallels of Ned Merrill and David. During his cross-county venture, Ned invites various people to join him (only a young woman does, but only for a short time), just as Lisa repeatedly insists that David play with her.

Neither character manages to articulate the purpose of the request to whom they are asking, but remain desperately persistent. From this, Perry makes the loneliness of human social interaction very plain and recognizable. This inarticulate request seems to echo the internal questions of these characters, which never manage to express themselves in dialogue, but rather in action. Like Ned Merrill, Lisa also sets out on a journey alone, to a place she identifies as “home” (a museum to which a field trip was made earlier in the film). Lisa’s home is a cold bronze statue depicting motherly affection, Ned Merrill’s home is a house long abandoned by his family. Both homes only have the potential for the social interactions these characters desire, yet they are incapable of fulfilling such desires; they are only illusions.

In both David & Lisa and The Swimmer Frank Perry investigates the more tragic qualities of human social interaction, a motif that in its moment was quite unpopular. It wouldn’t be till the murder of Sharon Tate that film audiences and Hollywood would begin to popularize such motifs in Perry influenced films like Five Easy Pieces (1970), Drive, He Said (1971), and Scarecrow (1973). However, looking back from the comfort of a cup of tea in 2012, Frank Perry seems ahead of his time, while still being fresh and relevant.