Nicolas Roeg’s death at age 90 can’t really be called a surprise, but the loss is still great. Personally, Roeg was one of my first “filmmaker heroes”. The first DVD I ever bought was the Anchor Bay release of The Man Who Fell To Earth. All of my life Roeg has served as one of my primary reference points in terms of my own filmmaking. So to celebrate and acknowledge this brilliant artist I am posting a piece I wrote in 2015 about his film Eureka.

Nicolas Roeg has enjoyed a career as a sort of filmmaker’s filmmaker. His films deliver delirious visuals in exceptionally iconoclastic montages that not only build upon narrative and character, but illuminate the psychological subtexts and connectivity of scenes, their images, and the overall visual complexes of the film. His most popular body of work is restricted to the seventies when auteurism was en vogue and audiences were more open to unorthodox employments of the cinematographic langue. Of Roeg’s work in the seventies his most enduring and popular contributions to the cinema include his collaboration with Donald Cammell, Performance (1970), his proper debut, Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), and The Man Who Fell To Earth (1975). Each of these films is aesthetically linked not only by Roeg’s inimitable visual style, but also by Roeg’s persistent exploration of narrative deconstruction; a sort of antithesis to the works of Sergei Eisenstein that still utilized Eisenstein’s methods counter to the filmmaker’s original theories as to their employment.

Yet, despite the momentous contribution to the cinema that these four films represent, Roeg’s work after The Man Who Fell To Earth is practically unknown, with the exceptions of Bad Timing (1980), insignificance (1985), and The Witches (1990). Films equally brilliant to Don’t Look Now and Performance, such as Castaway (1986) and Track 29 (1988), have been relegated to the singular purview of critics, scholars and cinephiles. Roeg’s work as a whole has yet to receive an adequate and detailed survey.

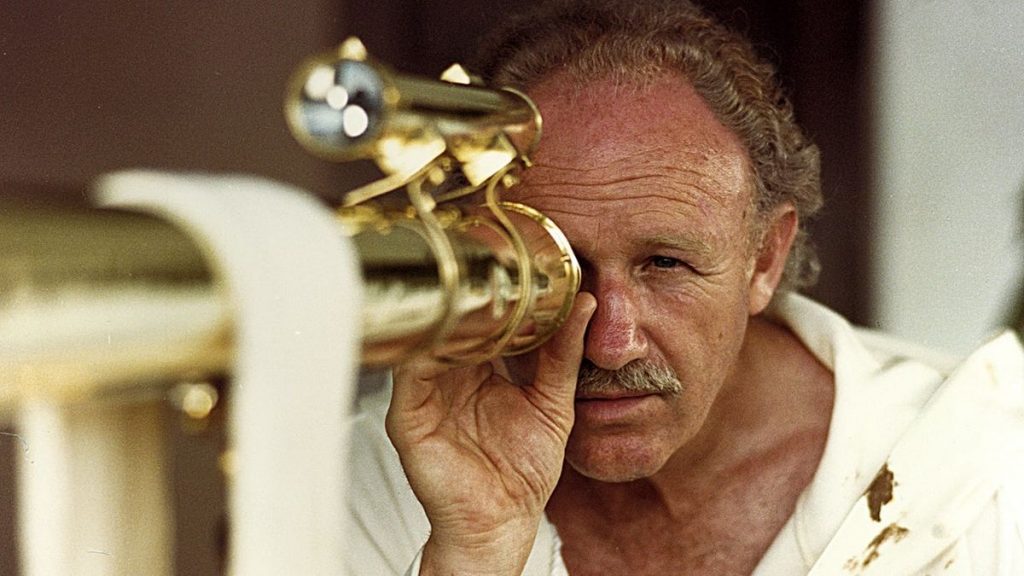

Now consider Gene Hackman. Hackman struggled for years to make a career for himself in the cinema, eventually breaking out in supporting roles in Robert Rossen’s Lilith (1964), Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde (1967) and John Frankenheimer’s The Gypsy Moths (1969). But, much like Roeg, Hackman would find his niche in the seventies, though his usual fare consisted of darker realist dramas such as William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), Jerry Schatzberg’s Scarecrow (1973), Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), and Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975). Hackman was not limited to these more sophisticated character portrayals, often playing camp inspired heroes and villains as well, most memorably in Ronald Neame’s The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie (1978), and Bob Clark’s Loose Cannons (1990). As the nineties progressed, Hackman stepped back, playing the smaller supporting parts like those that originally launched his career. But in 1983 Gene Hackman played the lead role of Jack McCann, with the same unbridled energy and machismo of his Lex Luthor in Nicolas Roeg’s masterful Eureka.

What may seem off handedly to be an odd pairing actually works extremely well. It is the camp of Hackman’s McCann that pulls off lines like “lay off the sauce” and “I never earned a nickel off another man’s sweat” with an other worldly naturalism. And it’s Roeg who has created this other world. Scenes such as the prospector’s suicide, McCann striking gold, McCann’s attempted murder of his son-in-law Claude (Rutger Hauer), Tracy’s (Theresa Russell) various love scenes with Claude, and McCann’s murder sequence are all brimming with the kinetic free-form energy and associative cutting that one expects from Performance. And it is Roeg’s visual wizardry and sense for melodrama that contextualizes Hackman’s campy Jack McCann so that every word he says and everything he does is perfectly justified; grounded within the world of Eureka.

Sadly, Hackman and Roeg’s tour de force is hardly known and rarely seen. Eureka was not a hit when it was first released and, unlike Roeg’s Bad Timing, did not receive its due critical reappraisal with a quality home video release in this country (there is a beautiful Region 2/B release available from The Masters Of Cinema line in the UK). Regardless, Eureka is a film well worth discovering. Recently I screened the film for an actor friend of mine and he was blown away, not just by Gene Hackman’s performance, but by Roeg’s unique visual language.