“Nervous breakdowns/Crowd the calendar of freedom/When reality is forced upon the nonbeliever’s ego plan/Criticizers/From the hanging cliffs of plenty/Laugh to see the fall of those/Who would remain in honest lands/Clairvoyants strive to see/The plans of those who need to know/What lies beyond the seeing tree of life” – Eugene McDaniels, Unspoken Dreams Of Light, from the album Outlaw, 1970

When I saw Detroit last Tuesday, I believe that I was fortunate enough to have a wholly unique viewing experience. I assume that unlike most white male viewers I had a special “tour guide” in the form of a running commentary from two elderly Black women seated directly behind me. In many respects this commentary provided a good deal that the film did not. Though these two women restricted most of their commentary to the fashions of 1967, their personal reminisces that accompanied these asides were highly enlightening. The Black Culture of 1967 that was too elusive in Detroit became almost tangible to me thanks to my fellow spectators. Now I cannot imagine making it through the entire film without them.

The fact that the cultural context for Detroit came not from the film itself but from my fellow spectators indicates the primary failure of Kathryn Bigelow and Mark Boal’s film. A film which sets as its objective the “education” of an audience should be more inclusive, prioritizing the context of its protagonists so that, from the vantage point of 2017, we may understand and even recognize the dramatic stakes proposed by the film. A recent publication in the Huffington Post, ‘Detroit’ Is The Most Irresponsible And Dangerous Movie This Year by Jeanne Theoharis, Mary Phillips, and Say Burgin, points to some of the major omissions of historical events as well as the political ramifications of said inclusions and omissions.

This half-hearted approach to Black Culture in a film made by white filmmakers condemning racism squarely places Detroit within the tradition of Richard Brooks’ or Stanley Kramer’s civil rights oriented films of the fifties and sixties. Kramer’s use of caricature, narrative cliché, and preachy dialogue seems out-of-place in a film of 2017; it may even be dangerous. When Stanley Kramer was making his films Oscar Micheaux had already completed more than two dozen films that had never been released widely to white audiences (J. Hoberman’s excellent essay on Micheaux is collected in his book Vulgar Modernism). Black filmmakers before 1970 were almost exclusively left to exhibit their films on a regional level (New York based filmmakers screened their work there, Memphis filmmakers screened their films there, etc). The segregation of American cinema in the fifties and sixties and even before is what makes Kramer’s films such important political documents. In other words, Kramer’s voice was one of the few audiences all over the U.S. heard at the cinemas on the subject of civil rights. Today Black filmmakers have found a more general mainstream acceptance, so issues of racism in this country do not have to wait for a “white savior” like Stanley Kramer to stick up for them. It is almost impossible to imagine what a filmmaker like Oscar Micheaux would have been capable of if he had had the opportunities of Tyler Perry, Lee Daniels, Barry Jenkins or Steve McQueen.

The films that have endured by white and black filmmakers alike about America’s racial conflict are the ones that have not sought to explicitly propagate one agenda over another. Charles Burnett’s The Glass Shield (1994), John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959), Ryan Fleck’s Half Nelson (2006), and Lee Daniel’s The Paperboy (2012) and The Butler (2015) all take an equally compassionate view of their characters regardless of race; prioritizing character over politics and thus finding something closer to the truth with regards as to how race affects human beings on an acutely personal level.

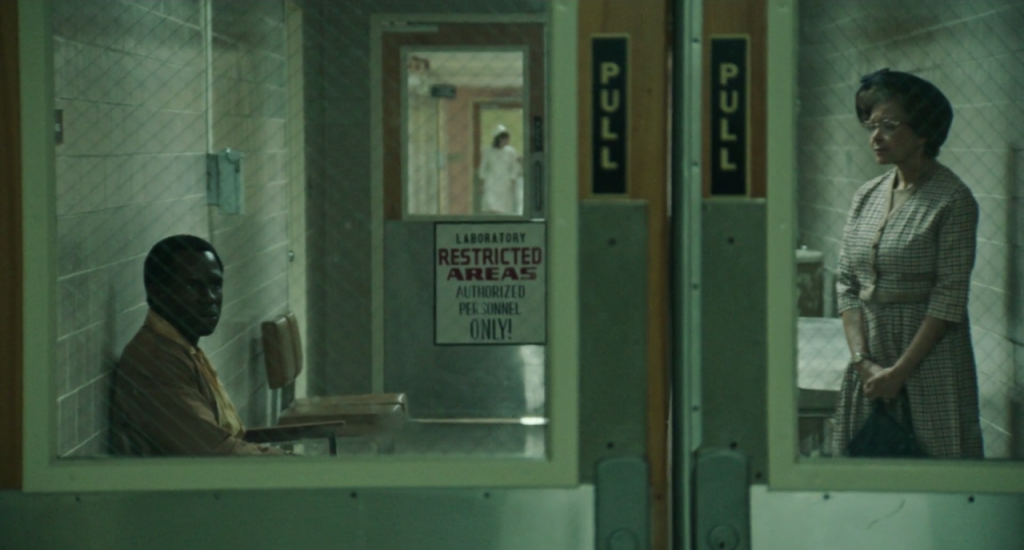

Detroit does not offer viewers human beings, only character types and sketches, distilling the life out of its characters both Black and White. This has the unusual effect of placing Detroit more in line, in terms of genre, with the home invasion thriller than with the historical drama. Detroit, like any good exploitation film, favors the spectacle of violence, reveling like a sadist in scenes of torture and depravity. The only “message” this tactic can offer viewers and the only understanding of the event in our history Detroit seems ready to share is that racism is violent and bad. This juvenile interpretation of these historical events both demeans its survivors as well as leaves viewers ill-equipped to address this kind of racial violence after seeing the film.

For myself personally, the truly frightening aspect of racism is that it can be found anywhere. People and co-workers one may assume one knows could in fact harbor some of the most revolting kinds of racism. Costa-Gravas’ film Betrayed (1988) takes this as its thesis, constructing around this idea a uniquely disconcerting thriller. However, this kind of terror can only be made manifest on the screen if the film attempts to construct actual characters.

Bigelow and Boal have most certainly accomplished the antithesis of their goal. Detroit does not work as a film about the Detroit race riots of 1967. Detroit is an exploitation film, dressed up with a major budget and sold as a quasi “historical revelation”. Its great accomplishment will be to offend, and in so doing prove just how out of touch White Hollywood still is with the problems of Black America today and yesterday.

This review was first published on March 22nd, 2018.