“Everybody wants a piece of your birthday cake/Fingers in the frosting, everybody wants to take/if you give an arm you can bet they’re gonna take a leg/living on this world is living on a powder keg”

-lyrics from the Hello People song Pass Me By

It used to be that the only way to see Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie (1971) was to purchase a VHS off of amazon for no less than $35.00. Lawrence Schiller and L.M. Kit Carson’s The American Dreamer (1971) was even more obscure. To see The American Dreamer one had to order a homemade DVD off the internet whose source material was a 16mm university print. Luckily this has changed thanks to Etiquette Pictures and Arbelos Films. Each film has been meticulously remastered and made available with a plethora of supplements.

This may not seem very important, but for years it has been very difficult to see one of the truly individual films produced by Hollywood. The Last Movie, in historic terms, finds the major cinematic trends of the sixties coming together in one desperate climax that marked the end of what Peter Biskind has called the “New Hollywood” before it ever really began. Hopper combines the reflexive elements of American Underground film and the genre deconstruction of the French and Czech New Waves with his own “identity in crisis” as the centerpiece. The American Dreamer operates similarly, but rather than tell the story of a fictional character the filmmakers opt to interpret Hopper directly, investigating the man, artist, and public persona that seems to be lost in the process of completing his masterpiece. In Alex Cox’s documentary Scene Missing (2017) it is observed, quite correctly, that Hopper’s scene circa 1969-1972 is now missing, and that both The Last Movie and The American Dreamer are essential documents of that moment in our culture.

Dennis Hopper shot The Last Movie in Peru on a budget of one million dollars courtesy of Universal Pictures. Universal was hoping that Hopper would provide them with a commercially viable art house film similar to Easy Rider (1969). But Hopper had something else in mind. Hopper wanted his film to be about the production of big studio pictures, and tell the story of the westernization of Peru by implementing reflexive tactics like those Godard had been using since 2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967). It would be Dennis Hopper’s naïveté as a filmmaker that would allow for the greatest innovations in his work bringing film art, the culture of the 1960s and studio run Hollywood together.

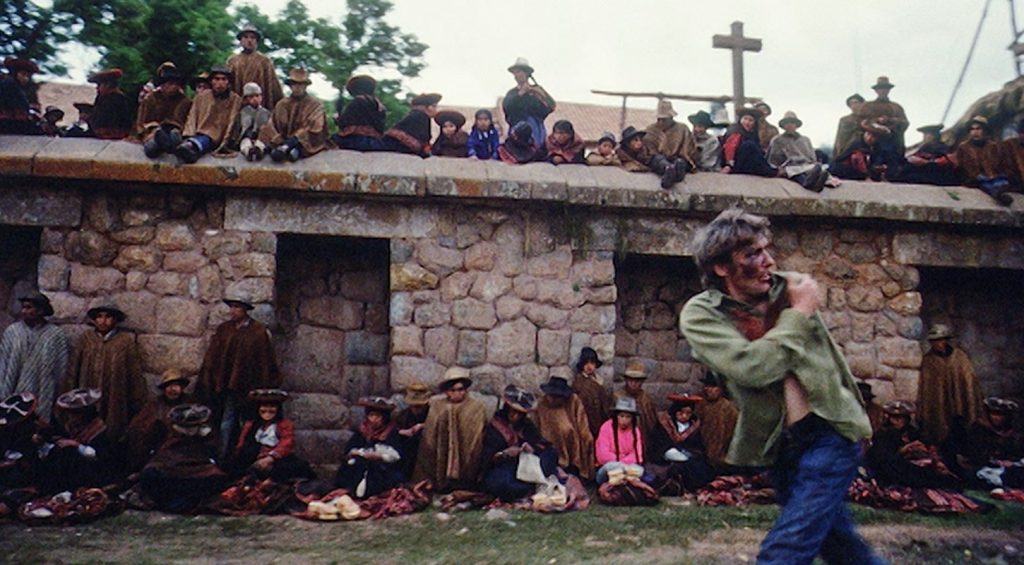

Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie is a film very much concerned with the medium in which it exists, and as both a narrative allegory and a technical deconstruction of the film process it analyzes the imperialist ramifications of the American film industry. The narrative tells the story of Kansas (Hopper), a Hollywood stunt double that stays behind in a Mexican village after wrapping a western directed by Sam Fuller (who plays himself). Kansas sets forth shortly thereafter in search of a local treasure. While Kansas embarks on his quest, the Mexican villagers begin to make a mock-film of their own with wooden cameras. It is the belief of the villagers that the camera grants immortality. After they replace the Hollywood cap guns with legitimate firearms, they find the “Hollywood star” Kansas and place him in their film as a sacrificial Christ figure.

The Last Movie is a film of diegetic sounds, but it is these sounds that are manipulated to distort the reality of Hopper’s film and inform the audience of the films technical aspects almost as if it were a feat of engineering. Sounds local to one scene will carry over into the next one (becoming then non-diegetic), dissipating as the new scene is played out. This is especially the case in the opening transition from film set to the film being shot by Fuller. At the conclusion of Fuller’s footage, which we’re invited to watch as if it were the narrative of the Kansas character, Kris Kristofferson begins to dominate the soundtrack as Kansas rides the mountainside. As the Kansas riding sequence wraps, it’s revealed that Kristofferson was seated nearby, and that the expectation of a Hollywood soundtrack was just a ruse.

Hopper’s constructions with sound, as mentioned above, are aligned to the same purposes as his editing style, which is to challenge how an audience perceives and understands a film. This ploy exceeds the simple “scene missing” title cards in its scope. The sounds, misplaced, are often similar to the documentary style sounds recorded for his previous film Easy Rider; most significantly during the New Orleans sequence. But it is in The Last Movie that Hopper truly finds a purpose for his “guerilla” style sound recording. It is arguable that the best way to distort through sound textual displacement is to use rough documentary sound. Documentary recording does not specifically focus on a character or action, but rather an entire event. Through both the opening and closing sequences a fiesta remains the most audible “image”, so to speak, but Hopper gives us a juxtaposition of pictures with no source for the sound. Hopper throws his audience happily into disorientation and confusion, but as they try to get their bearings they can only empathize with the movie making hell Kansas has entered. Hopper will also employ sound as a tactic to distance his audience by letting technical sounds through in the sound track (editing glitches and camera hum). After all Hopper isn’t interested in any strong narrative construction, but rather in the construction of film itself.

The music in Hopper’s deconstruction is essential, often juxtaposing the Hollywood norm with the psychedelic bizarre. A scene of Fuller’s where a man is shot on a roof and falls down features the sound local to a previous shot of an old woman hammering a stone wall. This is overlaid with Kansas talking to his female companion, but the hammering at the shot change becomes the transition to music that plays to link a series of shots of Kansas driving into a small Mexican town. The music stops only when Hopper cuts to the interior of Kansas’ car for a dialogue exchange. The entire film is composed of sequences with this sound track design. The odd thing is that Hopper’s use of pop songs is exactly that of the big Hollywood pictures his film is rebelling against, though often he’ll use diegetically recorded music to disorient his audience during pivotal scenes concerning the villagers decent into movie making madness.

The Last Movie’s dialogue is sparse but in sync with the sequences for which it was recorded when the narrative of Kansas needs perpetuating. Though, as mentioned before, Hopper will overlay indiscernible dialogue over shots with which there is total contrast. This is especially true at the climax of the film when Kansas is being escorted to his doom. The dialogue is structured to better reflect the atmosphere of the scene then it was in its predecessor, the cemetery sequence in Easy Rider. It must be reiterated, however, that The Last Movie may use many of the same sound track stylings as Hopper’s first feature, Easy Rider, but that The Last Movie uses these strategies in a constructive commentary while Easy Rider used those techniques for the highly superficial reason of depicting the psychedelic acid trip so heavily associated with the American counterculture of the late 60’s.

All things considered, Dennis Hopper’s lofty analysis of film in his epic movie within a movie serves as background to a more urgent commentary. The Last Movie, by design, exploits assumptions about Central and South America that have been perpetuated by Hollywood to engage his audience in a discourse around the idea that the presence of Hollywood, the land of dreams, actually bankrupts culture. Likewise, Kansas, as a mirror image of Dennis Hopper himself, comes to represent how the machinery of Hollywood manipulates and perverts the individual or, to use Richard Dyer’s term, “star”. This aspect of the film is the most self-indulgent, obviously, but it provides an important link to The American Dreamer as well as to understanding Hopper’s own personal need to make The Last Movie in the first place.

In 1970, L.M. Kit Carson and Lawrence Schiller turned their cameras to a bunker in Taos New Mexico to capture Dennis Hopper in post-production on his masterpiece. Hopper’s The Last Movie is a bit too cerebral and a bit too complex for mainstream consumption (and certainly for the studio). Universal Studios had, however, promised Hopper final cut of The Last Movie. Fearing that the stories of the film’s troubled production in Peru would cause executives to seize the film, Hopper fled to Taos New Mexico with all the prints and began editing in seclusion. Little by little, time passed and Hopper had become almost six months late for submitting the final film. In Taos, Hopper had run amok. While simultaneously cutting The Last Movie he was also assembling his photographs for exhibition as well as writing and acting in sketches for The American Dreamer.

Hopper invited Schiller and Carson to document not just the post-production of The Last Movie but his bohemian methods of film production which he believed to be the way of the future. Hopper also had some ideas about scenes, not totally scripted, to be shot for the film so that he may expound further on philosophical issues, the state of American Cinema, and a strange sort of performance art (Hopper, in one such sketch, removes his clothes in the middle of the street and walks two blocks naked through Taos). Hopper’s motivation for contributing these elements to the film is the link to The Last Movie. Hopper is playing with the different ways he is seen by the movie going public and seems to be working to eradicate all cohesive understanding by film goers of who he is and what he represents.

For Hopper’s purposes, the pairing of Carson and Schiller seemed ideal. Schiller had become famous as the photographer/journalist who not only took the last nude pictures of Marilyn Monroe but who also owned the rights to Lenny Bruce’s family’s life stories. Carson, on the other hand, had been working the New York underground film scene and had starred in the Jim McBride classic David Holzman’s Diary (1967). By bringing the two together Hopper felt he could equally showcase his staged moments of “inspired genius” while seamlessly blending them with documentary footage of him hard at work or hard at play.

The result stands as a testament to the freedom directors once enjoyed in the Hollywood studio system at the dawn of the seventies, as well as to why it lasted ever so briefly. In the film, when Hopper isn’t waxing philosophically about how he’s a lesbian, he’s shooting machine guns at cacti, smoking pot in the editing room and finally enjoying a massive staged orgy with Playboy Bunnies. The blending of the real and unreal images, the actual and the factual, does work. It becomes hard to separate the two when both are so fantastically out of this world. The cohesive and constant truth about Dennis Hopper the man and artist that runs through the film can be found in this dialogue.

From what Hopper has to say it’s clear that he’s paranoid. He fears that if The Last Movie should fail he’ll suffer Orson Welles’ fate in American Cinema; his acting will be relegated to B-pictures or European films and his efforts at directing will be largely ignored. All of Hopper’s crazy musings are prophetic of not only his career for the following decade and a half, but even in regard to his personal life. In this way, looking back from the comfort of 2019, there is something horribly tragic about The American Dreamer.

As a film, The American Dreamer appeals more as a slice of film history than any film I can think of. Dennis Hopper is destroying himself, his career and the people that compose his entourage. He is ignorant, decadent, and an egomaniac. Though The Last Movie is today considered a classic at the moment The American Dreamer was made the studio had already ensured that the film would fail. Considering the films’ titles and what is contained there in, it all seems too fitting.