This film is much more radical than Greetings. It deals with the obscenity of the white middle class. And we are white middle class, Chuck and I and everybody we know. So we’re making a movie about the white middle class. And we’re using the blacks to reflect the white culture. Because the blacks stand outside the system and they see what we are.-Brian De Palma, 1970

Much of Taxi Driver arose from my feeling that movies are really a kind of dream-state, or like taking dope.-Martin Scorsese, 1988

Perhaps by the 90s a sufficient time gap will have elapsed to allow filmmakers to approach the subject of Vietnam in a more detached, balanced, and analytical manner. -Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1980s

The Vietnam War remains a difficult subject for the United States. It is an ambiguous anomaly, devoid of any easy label or justification from the stand-point of a contemporary American perspective. The most popular American films about the war, Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986), John Irvin’s Hamburger Hill (1987), Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), and Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987) avoid the political aspects of the conflict as well as the Vietnamese experience. These films prefer the traditional heroism of the G.I. action-drama popularized by the first two World Wars. This preferred model mandates that the reality of Vietnam, the way it truly did happen and what it meant, undergo a severe filtering process so that it may accommodate the binary model of black and white, good and bad. To say the least this is an irresponsible approach to history, even if that history is particularly ugly and embarrassing.

Perhaps the best film about the Vietnam War ever made in America is Robert Kramer and John Douglas’ Milestones (1975). Unlike the other films I mentioned, Milestones does not take the battlefield unto its purview. In total contrast the film never ventures outside the United States themselves, focusing exclusively on the experience of the Vietnam War in America. Over the course of an epic 195 minute running time Kramer and Douglas construct a series of interwoven narratives with over a dozen characters, touching on every subject on the national conscious in 1975. That is to say by not focusing attention on the Vietnam War, Kramer and Douglas have been able to paint the most accurate portrait of the United States and life therein during that traumatic conflict.

To juxtapose the American experience of Milestones is Chris Marker’s monumental anthology film, made in collaboration with Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, William Klein, Joris Ivens, and Jean-Luc Godard, Far From Vietnam (1967). Far more cinematic than Milestones, Far From Vietnam pits the left of the French avant-garde against the Imperialist Western powers, creating a film whose sympathies and varying perspectives are aligned with those of the Vietnamese themselves. In a sociological and political context what is so iconic about Far From Vietnam is that the film dared show in detail what Peter Davis’ Hearts & Minds (1974) only dared to allude to; the celebratory nature of American violence against the Vietnamese people. In the American cinema the closest element to such depictions we have come from Marlon Brando’s Col. Kurtz in the form of monologues during the third act of Francis Ford Coppola’s post-Vietnam spectacle Apocalypse Now (1979). But Coppola’s film is far more concerned with the literary motifs of Joseph Conrad and the conventions of the “war film” genre to delve to the political depths of Far From Vietnam.

Now one may be beginning to wonder where Robert De Niro comes into all of this. Well, it is not my intention to discuss The Deer Hunter any further than I already have. It’s Gilgamesh classicism and deceptive visual realism have little to do with Vietnam as far as I am concerned other than as a tool by which one can begin to gauge how the generation that experienced the war first hand began to censor its history in the media. No, my focus will not be on The Deer Hunter. Instead, I prefer two early Brian De Palma films, Greetings (1968) and Hi, Mom! (1970).

Be it an aesthetic choice or a necessity, De Palma, like Kramer and Douglas, focuses his two films on the American people during the Vietnam war. Yet, where Kramer and Douglas have constructed a somber narrative film deeply rooted in the realist tradition of American independent film, De Palma has gone instead for the madcap satirical stylings of Jerry Lewis. The same fundamental truths about America at this time can be discerned from either Milestones, Greetings or Hi, Mom!, De Palma simply exaggerates these truths to comedic effect, taking the stance that Vietnam, and all of its ramifications included, is an absolutely absurd venture. De Palma is also not so heavily rooted in the cinematic traditions Robert Kramer represents, who is strictly concerned with inciting political reaction in his audience, evidenced by his film Ice (1968), which, coincidently, came out the same year as Greetings. What De Palma sees in his approach is the possibility to play with the physical medium of film, manipulating the form to achieve effects that will only accentuate the humor and meanings in his two films, an ideology Lewis had demonstrated in his films since the late fifties.

What links Greetings and Hi, Mom! is not exclusively De Palma’s filmic sensibilities of the time, but the character of Jon Rubin played by Robert De Niro. In the first film, Greetings, Rubin and his friends are determined to do three things. The first is seduce young women, a trope of the underground film comedy. The second is to uncover who is responsible for the assassination of John F. Kennedy, though they never get further than reading countless books on a variety of conspiracy theories. The third objective is to dodge the draft. For all of De Palma’s innovative POV shots and handheld camera work the film never escapes the innocence of its comedy. The film’s approach to draft dodging is so light and comedic that it becomes indicative of the severity of the issue. De Palma is simply unsure of how to parody the subject successfully so that his satire would truly mean anything, so the entire sequence becomes imbued with a suffocating paranoia.

Hi, Mom!, the sequel to Greetings, is a far more mature and darker piece of filmmaking. Robert De Niro returns as De Palma’s protagonist Jon Rubin, though this time Rubin has recently returned from a tour of duty in Vietnam. Thus Hi, Mom! is a darker comedy concerned with how a man re-assimilates into a society from which he has been absent for two years. Firstly, De Palma pits Rubin against the sexual revolution. Never successful with women in Greetings, it becomes doubly comedic in Hi, Mom! that Rubin choses to be a pornographer by profession. Rubin’s scheme is to film on a cheap 16mm camera the sexual antics of the residents in the apartment building across from his squat. So at once De Palma parodies the fetishism of James Stewart’s lens in Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) and alludes to Rubin’s role as a sniper in Vietnam, tampering with the POV shots of what Rubin sees through his camera to look like the view through a sniper rifle scope. For De Palma the two signifiers are synonymous, indicating the degree of Rubin’s perversion.

However, Rubin is unable to capture any worthy sexual acts. So, having chose a particularly lonely woman across the way(Judy, played by Jennifer Salt) as a victim, he poses as a suitor selected by a computerized dating service to take her out and, hopefully, seduce her. To capture his plan on film, he has set his camera to begin running via a timer so that, after he has wined and dined her, his intercourse with her will be captured on film. Needless to say Rubin fails at this. The only result of his scheme is that he has acquired a rather needy girlfriend.

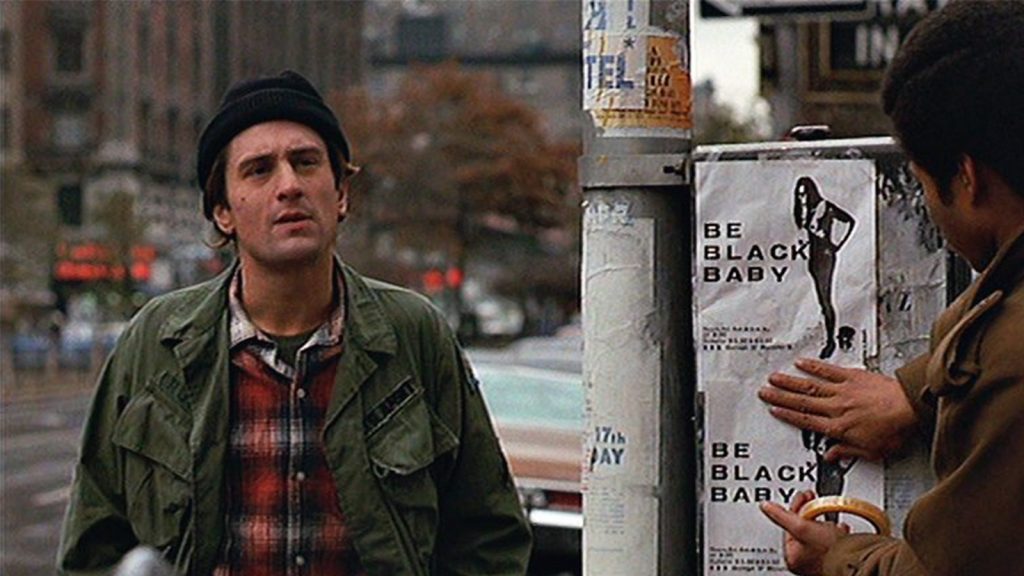

Rubin, now living with his girlfriend Judy, is still an outsider in American society. In an effort to belong he joins a group of Black Power activists as an actor cast as a cop, thus beginning the most controversial section of De Palma’s film. The “Be Black Baby” segment is visually different from either the primary narrative of Jon Rubin or the attempts at pornography Rubin has photographed. In this segment De Palm shot handheld on black and white 8mm blown up later to 35mm. In this way he employs the visual aesthetic of late sixties “social action” documentaries to capture his satirical indictment of Black militarism and the white yuppies who claim to sympathize and understand the Black Power movement. “Be Black Baby” follows a group of upper middle class white people who, eager to undergo the “black” experience, submit themselves to a piece of avant-garde living theater. The white audience is physically beaten, painted black, and then beaten again by Jon Rubin. Then, after all of this violence, each comments how wonderful it was to finally understand what it means to be “black”. As offensive as it is funny, the “Be Black Baby” segment scandalized audiences during Hi, Mom!‘s original release.

After his turn with “Be Black Baby”, Rubin is still a man isolated in a society he no longer understands. This is when De Palma begins to hint at Rubin’s Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Every attempt at normalcy Rubin has made thus far has either been perverted or simply perverse to begin with. Thus, for De Palma, PTSD is the catalyst for Rubin’s comedic exploits. Rubin, seen at this point in the film reading militant literature and being inundated by media slogans, both for the Left and the Right, reading “take action”, begins to snap. And snap he does. Filling the laundry room in his apartment building with plastic explosives, he demolishes the building, killing Judy and countless others. Now, De Palma cuts to the POV of a television camera as a reporter interviews witnesses and survivors of the “act of terrorism”. Rubin appears in his army uniform, faces the camera and says “hi, mom!”.

Again, one must stress that De Palma has exaggerated the conditions of both veterans of the Vietnam war and the state of things in America for comedic effect. However, these exaggerations are born out of a real truth, because if they were not, then Hi, Mom! would not have been funny or relevant. It also bares pointing out that the trajectory of Jon Rubin, particularly in Hi, Mom!, mirrors that of another Robert De Niro character, Travis Bickle of Taxi Driver (1976). Rubin and Bickle are both veterans of Vietnam unable to find a place in their society after the war. Each has a penchant for pornography and violence. Where they differ is simple, in the execution of their narratives by the filmmakers who have authored them. For Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader Travis Bickle’s story is one of loneliness and pain. Rubin, though suffering the same symptoms, has more unorthodox ventures in his attempts at being proactive. This unorthodoxy to Rubin’s narrative is what makes it comedic. That both Taxi Driver and Hi, Mom! follow the same logic indicates a moral truth that America, during and immediately after the Vietnam war, was struggling to grapple with; how does one atone for what one has done?

The issue of atonement is not unique to the Vietnam war in the American experience. Literature by the major players of every military conflict have reflected such sentiments as far back as the American Civil War and still further. Even, at times, these sentiments have been articulated in satire similar to De Palma’s two films, consider Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple. What is incredible about Greetings and Hi, Mom! is that, of all the films either Brian De Palma or Robert De Niro have made, neither have ever been as sociologically relevant again.