“He (Pontecorvo) has no fucking feeling for people.”-Marlon Brando

By the time Marlon Brando signed to star in Burn! (1969) he had starred in a string of box-office flops including The Night Of The Following Day (1968) and John Huston’s lyrical erotic masterpiece Reflections In A Golden Eye (1967) as well as having turned down the lead in Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid (1969). Brando’s expectations for Burn! were matched only by the film’s director, Gillo Pontecorvo, who hoped to combine the romantic adventure film with the “idea movie”. Unlike Brando, Pontecorvo’s previous film The Battle Of Algiers (1966) had been a critical sensation, as popular as it was influential. Perhaps Brando’s decision to work with Pontecorvo was motivated by the need to achieve both a critical and commercial legitimacy that had sorely been lacking from Brando’s career during much of the decade.

Burn! follows William Walker (a character of fiction named for the historical revolutionary who is the subject of the Alex Cox film Walker) as he instigates a rebellion in Queimada, only to return a decade later to suppress it. Both the character of William Walker and the location Queimada are fictitious inventions of Pontecorvo’s, designed to stand in for the actual events that occurred in Guadeloupe during the early nineteenth century. Allegorically speaking, the film is intended to indict colonialism and capitalist intervention, two themes that dominate Pontecorvo’s The Battle Of Algiers. Where The Battle Of Algiers focused on a contemporary uprising intended to instigate anti-imperialist sentiment, Burn! works as a metaphor for the American involvement in Vietnam, with the Brando character representing America.

The technical mechanisms at work in Burn! are not unlike those in The Battle Of Algiers. The intervening years between the two films saw a tremendous number of imitators of The Battle Of Algiers aesthetic (Peter Watkins in particular seems to have been greatly influenced by the film). This prevents Burn! from achieving the sense of urgency at the heart of The Battle Of Algiers, or the freshness of its cinematic style. By 1968, numerous films had employed the kinetic camera movements and the hand held camera techniques Pontecorvo employs in Burn! This doesn’t hurt the film, it simply inhibits the films ability to emote with American viewers, relegating those duties almost exclusively to Brando.

What is significant about Burn! is its depiction of European intervention in the South Americas. Walker arrives in Queimada to help overthrow a Portuguese ruler and liberate the island. The liberation is achieved with considerable damage to the economy. The ruler Walker set-up becomes disinterested in trading with the European nations, plunging the country into poverty. Years later, Walker returns as a British representative and aids in the execution of the very ruler he had put into power. Walker’s behavior is motivated solely by monetary gain. Though he is aware of the sociological ramifications of his actions, he suppresses them in favor of his benefactors. The imperialists of Burn! are completely detached from the human conflict at hand, treating the people of the island with a cold harshness. Pontecorvo is able to convey the polarity of the conflict by reserving his documentary style for when he photographs the rebellion, opting to photograph Walker and his allies with more conventional tactics. The polarity between these two parties pits Brando as America’s substitute clearly against the native people’s socialism; film classicism against innovation.

Of the political messages that abound in Pontecorvo’s film the most troubling is his approach to slavery. His depiction is all too accurate and all too brief within the film, standing alone as a haunting two minutes lost in a film that runs just shy of two hours. In Burn!, Pontecorvo presents his audience with a Europe of imperialist governments and corruption whose primary motive for discarding slavery was not a moral one, but an economic one. When the slave trade was no longer profitable, the slave trade ceased to exist. In popular western cinema such a radical depiction was unprecedented and may help to explain why it was so lightly touched upon, avoiding villainizing the character of Walker. The depiction of slavery outlined above would later be given a clearer voice in the late seventies by the Cuban filmmaker Gutierrez Alea, whose film The Last Supper (1977) is instrumental to understanding the perspective of the South Americans in the conflict.

The Battle Of Algiers also shares with Burn! a tragic ending. The instigators of revolution in both films are assassinated at the films conclusion. The concept of the “legend” is also approached in a similar way. Pontecorvo suggests in both films that the leaders of rebellion die in a sort of martyrdom, that their contributions ensure that the revolution carries on and that their names become synonymous with it, achieving a legendary status. In hindsight, this is not entirely true. Let us reconsider the Vietnam analogy.

The French once had a colony in Vietnam as they had in Algiers. When the French were met with resistance, they called upon the United States for assistance, just as the rebels initially call on William Walker in Burn!. The French all but disappear from the Vietnam conflict after a few short years as America wages war in the name of democracy and anti-communism. This transition in Vietnam into an American conflict is represented by Walker’s return to the island to quell the rebellion. Again, Pontecorvo insists that his audience see the political agendas in his film and in real life in black and white terms. Pontecorvo’s stance is clearly anti-Vietnam just as it is anti-colonialism, which in this case seems to overlap somewhat. Pontecorvo has cleverly villainized all political movements and ideas that do not exhibit an interest in the needs of the people, particularly the impoverished and the minority (socialism). Burn! has the benefit of exhibiting historical concepts that are easily understood from the perspective of hindsight, but suffers as an allegory for more contemporary political conflicts.

The two dimensional depiction of politics in Burn! indicates a trend in the mainstream of narrative filmmaking of the late sixties. Comparing Pontecorvo’s work with that of Costa-Gravas, certain narrative tendencies become more and more evident. That the revolutionary tactics of the left during the late sixties, even their views, do not translate easily into the narrative form. For example, Pontecorvo’s attempt to codify the Brando character by naming him William Walker appears a bit contrived and pretentious by 1969.

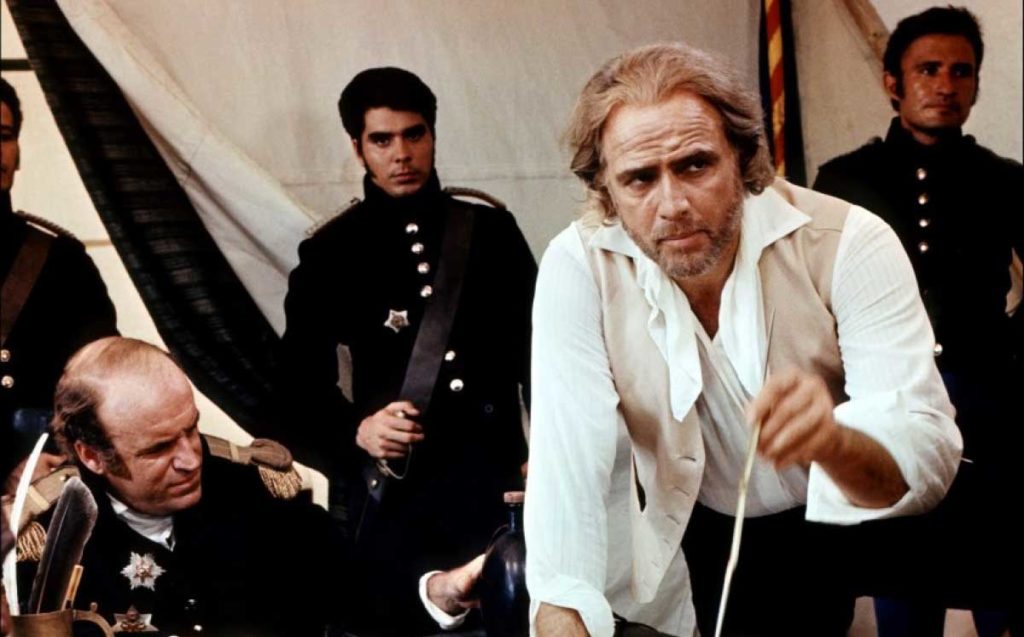

Interestingly, Marlon Brando’s liberalism is what first attracted him to Burn!. Though his views were more to the extreme than Pontecorvo’s, their personal conflicts on the set stemmed from a different place entirely. The production of Burn! was troubled by non-actors and problems arising from the multitude of locations used in the film. Brando had to pass on a number of projects because of production delays and his own inflated ego that dictated his celebrity treatment. Despite all of these conflicts, Burn! contains one of Brando’s very best performances, on par with his work in The Fugitive Kind (1959) and Last Tango In Paris (1973).