Recently I received as a gift ANDY WARHOL Polaroids 1958-1987, published by Taschen. It is a marvelous presentation of Warhol’s work, quite fascinating when one begins to compare these original Polaroid portraits with the more famous paintings that were born from them. However, given recent events this month, I have been particularly drawn to a photograph Warhol took of David Bowie during his first visit to New York in 1971.

Bowie’s admiration for Warhol has been well publicized by Bowie himself during this period. He did, after all, write a song for singer and actress Dana Gillespie about the Pope of Pop that he himself recorded for his own Velvet Underground inspired album Hunky Dory. Similarly, Warhol’s dislike for Bowie’s song has been equally well publicized by Bowie biographers Tony Zanetta, Marc Spitz, and Warhol biographer Bob Colacello.

Despite these comic differences, Bowie and Warhol are both men of ideas. Artists with the uncanny talent of taping into the zeitgeist, for surrounding themselves with fascinating, creative, and iconoclastic individuals. Without these individuals, the productivity and innovation we have come to associate with Warhol and Bowie would look very different. Bowie has credited a good deal of his glam rock persona to Andy Warhol’s Pork‘s London production, whilst Warhol very rarely ever credited anyone for giving him any ideas. Though famously Warhol had his collaborators (Billy Name, Ondine, Paul Morrissey, Fred Hughes, etc) and so did Bowie (Tony Visconti, Mick Ronson, Luther Vandross, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, Carlos Alomar, etc).

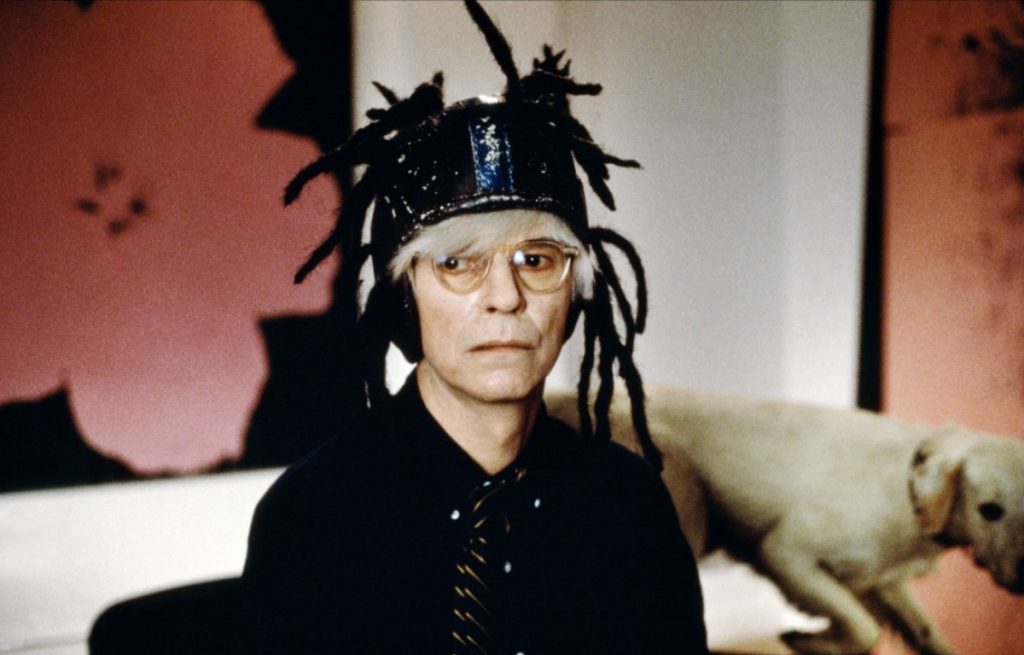

All of this considered, this tangled web of celebrity, the portrayal of Andy Warhol by David Bowie in Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat (1996) begins to be far more than it initially appeared to be on the surface. In 1996, Bowie was Warhol, he had transformed, even if only on the screen, into one of his idols. But if the Bowie of 1971 represented the absolute celebrity status of Warhol at that time, then Dennis Hopper must represent the beginning of the rise of Warhol’s star in 1963.

When Warhol had his second show in LA, it was Dennis Hopper who threw Warhol his first glamorous Hollywood reception (this reception began their lifelong friendship). In Basquiat, Hopper plays Bruno Bischofberger, Warhol’s European art dealer. When the film introduces us to Warhol, it is in the pairing of Hopper and Bowie, the “journey” and the “achievement”. In Basquiat Warhol is more of an aura than a tangible character; other characters even talk about him as if he were somehow not of this world. By 1996, this was undoubtedly true. Warhol had been dead for nearly a decade. His brand, his persona had since (as it very much continues to today) permeated our culture absolutely. Warhol has become Mickey Mouse.

It’s as if no one can ever play Warhol, not even Crispin Glover. Schnabel’s Basquiat does not rely on Bowie’s immense talents alone to give life to Warhol. The film itself, through the script, through the performances, and through Hopper is coordinated to make Warhol this omnipresent being residing in the New York of Schnabel’s film, a New York that might as well be the entire country. Schnabel wisely knows that this is the only effective tactic to give dimension to the unusual relationship Warhol had with the subject of his film, Jean-Michel Basquiat.

It is a clear instance of immortality. If Warhol’s presence in our mass culture has flourished after his death, why not David Bowie? Bowie’s decade long hiatus has already proved the staying power of his art, image, and persona. He has become an icon for LGBT groups, a musical deity for musicians, an inspiration for fashion, etc over the course of his life. His powers as an artist were even celebrated in his own times as a kind of myth by filmmaker Todd Haynes. Bowie and Warhol have been such an integral part of the 20th century’s cultural identity that they have negated death.