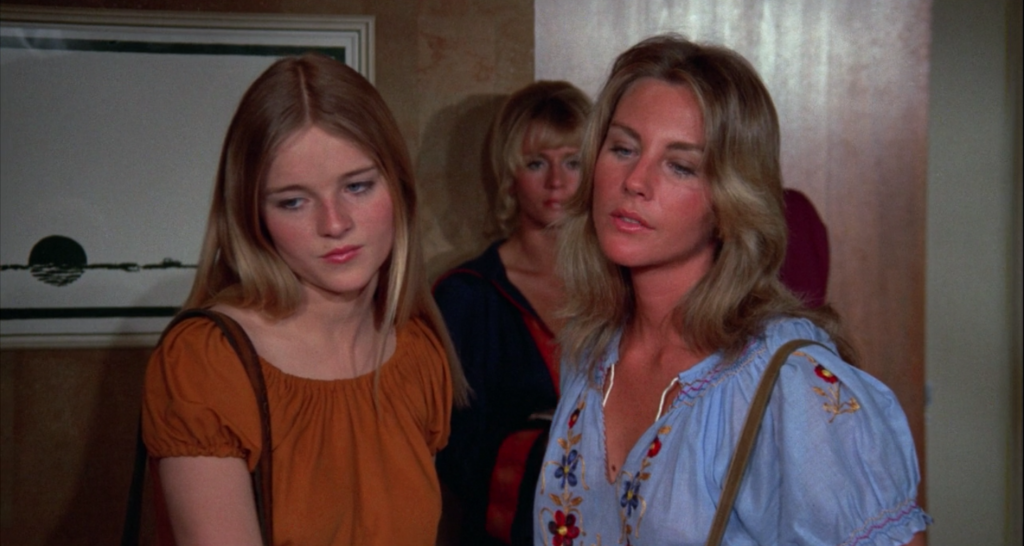

After killing their abusive stepfather (Leo Gordon), sisters Ellie (Tiffany Bolling) and Myra (Robin Mattson), run away to their estranged uncle Ben (Scott Brady). While Myra becomes sexually entangled with Ben’s wife Diana (Lenore Stevens), Ellie gets involved in Ben’s business affairs. On a job to collect a package for her uncle, Ellie hatches a scheme with P.I. Larry (Steve Sandor) to keep $40,000 for herself. But it isn’t long before the sisters are in over their heads with two hitmen (Timothy Brown and Alex Rocco) in pursuit of Ellie and Diana’s suicide.

Bonnie’s Kids (1973) is writer and director Arthur Marks’ best known picture. Unpredictable, morbidly funny, aggressively misogynistic and well written, Bonnie’s Kids is a cult classic that represents the pinnacle of the seventies drive-in feature. The title itself is, like the film’s final shoot out, a reference to Bonnie & Clyde (1967) designed to ground Bonnie’s Kids in that tradition of crime-adventure film.

But Myra, Ellie and Larry are far more real than Bonnie and Clyde. These are characters who, within the narrative complex of the film, spend as much time just hanging out as they do participating in the plot. When the latter is actually the case these protagonists prove themselves to be rather sloppy criminals. One of the best examples of this occurs when Ellie goes to shoot a cop but when her bullet hits the officer he himself fires his gun, striking Larry in the process. Bonnie’s Kids is a study in organized chaos; examining how reality interjects itself into romantic illusions.

Marks’ style as a director is competent and workmanlike; efficiently delivering dramatic beats and titillating spectacles just as expected. Marks’ real gift is in his writing. He takes a pretty well worn formula and is able to subvert the genre subtly by inventively imagining how certain tropes might actually play out in the real world. But more than that, his gift for naturalist dialogue is able to make archetypes feel like organic, multi-dimensional beings. The pleasure of an Arthur Marks’ film is always his ability to make characters from the dregs of society people that the audience just wants to hang out with. It’s this quality that Quentin Tarantino, a vocal admirer of Marks’ films, has been emulating in his own work for decades.

It’s in Bonnie’s Kids that one can locate many of Tarantino’s stylistic signatures. The two hitmen in Bonnie’s Kids are directly recreated in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994). Likewise Tarantino’s penchant for making genre pictures where everything goes wrong that can go wrong is merely an extension of Marks’ own brand of genre subversion. Even Larry’s wound in Bonnie’s Kids becomes Tim Roth’s wound in Reservoir Dogs (1992).

As dated as Bonnie’s Kids is, it is still a must-see picture. It won’t be to everyone’s tastes but its legacy, which extends beyond Tarantino, is such that to ignore Marks’ contribution to American cinema is to lose the chapter in history that made many of the films in the late seventies and eighties possible. Walter Hill is another filmmaker who comes to mind that wears the influence of Arthur Marks on his sleeve. Bonnie’s Kids is melodramatic, sleazy, violent, and just plain weird; an bonafide classic.