Backtrack (1992) opens with concept artist Anne Benton (Jodie Foster) witnessing a mob enforcer (Joe Pesci) executing a man at a refinery. On the run from the mob, Anne turns to two police detectives (Fred Ward and Sy Richardson) for help. When police protection proves futile, Anne disappears and assumes a new identity in New Mexico. Unknown to her a mafia don (Vincent Price) and his right-hand man (Dean Stockwell) have hired a seasoned hit man named Milo (Dennis Hopper) to kill the artist. But as Milo pursues Anne for several months he becomes more and more obsessed with her and ultimately kidnaps Anne rather than murder her.

Catchfire (the disowned theatrical cut of Backtrack) was released the same year as Dennis Hopper’s other neo-noir feature The Hot Spot (1990). In both instances Hopper subverts the genre largely by updating its various tropes along with its sense of period (from the forties to the nineties). Unlike The Hot Spot or Catchfire, Backtrack is meant as a far more personal statement by Hopper on both his philosophy and mode of filmmaking as well as the enduring legacy of the noir feature. Though not entirely successful, Hopper’s much publicized director’s cut Backtrack makes for a compelling double feature with The Hot Spot.

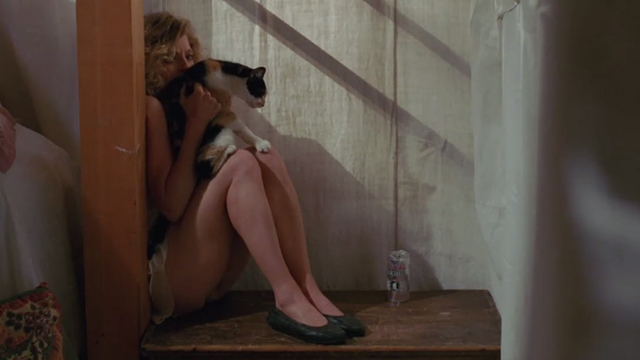

Anne, a concept artist, represents a kind of innate creativity or muse to Hopper’s Milo who represents action in its most destructive form. For the first act of the film Milo spends his time immersing himself in the world of Anne’s art, gradually growing to covet Anne’s intelligence as well as her individuality. For Milo and Hopper to catch Anne is to capture the creative impulse and free himself from the conventions of the genre.

The relationship between Anne and Milo as they flee gangsters and cops is as much about Stockholm syndrome as it is about a search for a means to deconstruct the very nature of film. Hopper attempts to perform the same aesthetic feats as he did in The Last Movie (1971) on a smaller and more commercial scale. While Hopper never achieves the reflexive brilliance of his second feature he is able to suggest some provocative notions regarding the state of American cinema in the early nineties.

For instance, the production design and cinematography in Backtrack collaborate to create images seemingly pulled from the pages of an issue of Art Forum at the time. This suggests that film as a series of still images rapidly projected must, on an individual scale embody a certain artistry that is wholly commercial in its intent. Likewise Milo’s gaze is merely an extension of Hopper’s active gaze as the camera eye via his role as director. The jobs of filmmaker and actor have metamorphosed in Hopper’s work since The Last Movie from that of renegade macho auteur to that of a commodified macho trademark.

Even though Hopper successfully suggests these concepts in his director’s cut of Backtrack, he fails to create any compelling drama. Backtrack is intentionally familiar in its narrative and that works for Hopper’s deconstructionist methodology. The issue is that Hopper and Foster, the dramatic heart of the movie, have absolutely no chemistry. Foster and Hopper infamously hated each other on set and that carries over to their work in front of the camera despite their best efforts.

While Backtrack was a troubled production for Hopper he nonetheless peppered the film with a number of his signature touches. Not only does Hopper continue to cast his buddies in different roles, but he once again returns to his beloved New Mexico. But these are all superficial touches devoid of the kind of cathartic self-portraiture that made his film Out Of The Blue (1980) a rare masterpiece. Milo as a character fails to delve into the most private recesses of Hopper’s psyche. Milo can be an extension of Hopper’s aesthetic program but Hopper can never truly inhabit the character on an intimate level. In the end Backtrack is mostly sustained by the plethora of big name supporting actors who were cut out of the theatrical release.