Intuition is responsible for a majority of the most fascinating works of art ever created. Throughout the ages artists have made decisions concerning their work in direct response to their intuition. Consider for a moment the stream of conscious poetry of Kenneth Rexroth, or the nonsense lyrics of John Lennon. Each artist has crafted something meaningful and iconic, and neither artist was ever quite sure of the purpose of his or her work while composing it. The artist’s intent has very little to do with the final product in most cases, strictly because of the audience’s interpretation, as well as the artist’s removal from the interaction between the work and spectatorship. Neither observation is strictly true, but it is true more often than it is not. Either way, this distinct separation of intent and accomplishment is one of the defining characteristics of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s films.

Jodorowsky is one of the greatest image-makers the cinema has ever produced. If one cannot find justification for his work in their philosophical quests or political satires, one can surely find something redeeming about his images. The Holy Mountain (1973) is an endless barrage of surrealist visions and acid induced nightmares. From a room of wax figures of Christ to the giant toilet to the invading army of frogs; each sequence is distinctly unique, and even more distinctly Jodorowsky.

Jodorowsky’s most famous feature El Topo (1970) is a reimagining of the tale of the Buddha as a gunslinger, which then diverts clumsily into the Christian mythos. The Bunuelean themes of El Topo and The Holy Mountain, along with Jodorowsky’s use of obvious signifiers, and his misogynistic tendencies, polarize the academic reception of his work. Critics and scholars are divided, some arguing that Jodorowsky has brought fine art to camp and the exploitation film, while others dismiss Jodorowsky altogether.

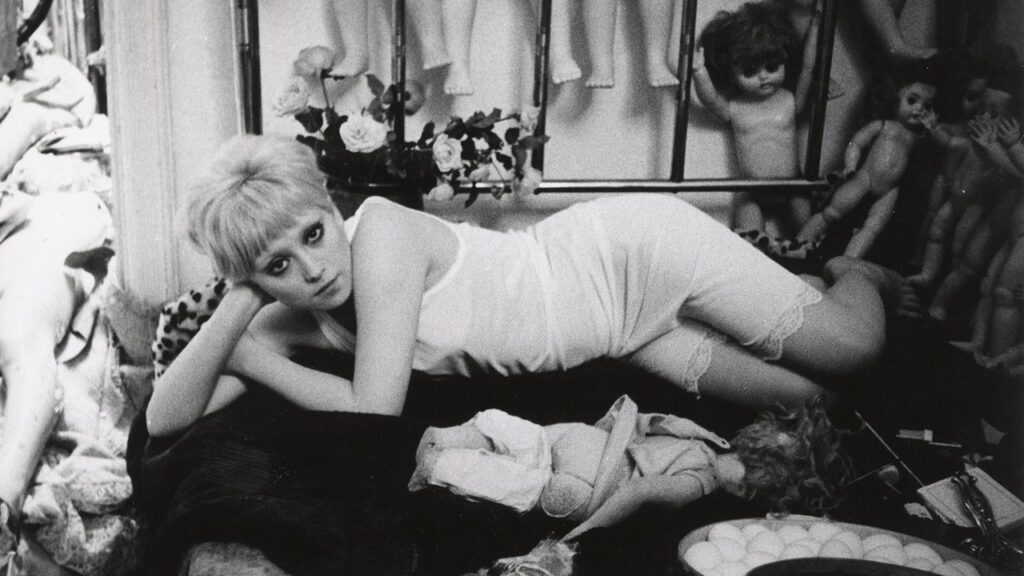

Fando Y Lis is fortunate to be Jodorowsky’s only feature to come close to succeeding on all levels. For once, the content of the film’s philosophical message is not outdone by camp imagery, but is accentuated by the imagery. Fando Y Lis recalls the best moments of Bunuel’s Simon of The Desert (1965) and The Exterminating Angel (1962) while also drawing upon the likes of William Klein’s Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1965) without ever giving the impression of simply imitating Bunuel or Klein. Jodorowsky manages to ground his most bizarre images in a dreamy yet tangible world, where subtlety (by Jodorowsky standards) prevails. Arguably the major problem with El Topo and The Holy Mountain is the excess of over the top images, which only dulls their meaning and gravitas. It is this subtlety that prevents Fando Y Lis from reaching the cult status of either El Topo or Santa Sangre (1989). Its themes are not so easily codified and its images are not so far fetched, so in turn it is not as easily digestible to the average “hipster”. Still, the stigma remains, preventing Fando Y Lis from achieving the critical reevaluation it deserves.

The bottom line is that the academic world has been too pretentious while the public has been too ignorant. I find that there are enough redeeming factors in a Alejandro Jodorowsky film to merit multiple viewings and some sort of reevaluation. Too often in the world of art do critics and audiences allow different stigmas to inform their considerations of works of art.