Abraham Lincoln (1930) was the first of two talkies that D.W. Griffith directed. In many ways Abraham Lincoln is more of an apologia than Intolerance (1916) was for the controversial The Birth Of A Nation (1915). Griffith’s cinematic oeuvre charts that transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth centuries with films such as The New York Hat (1912) and The Birth Of A Nation on one end and The Musketeers Of Pig Alley (1912) and Broken Blossoms (1918) on the other. But even as Griffith’s politics and aesthetic methodologies changed over time he never lost the profound influence that the romantic late-nineteenth century melodramas had had on him as a young, struggling actor.

It isn’t an exaggeration when critics refer to D.W. Griffith as the most influential filmmaker of all time. The kineticism of Griffith’s Civil War pictures paved the way for Eisenstein just as the silent close-ups of Broken Blossoms predicted the artful dramas of Murnau, Pabst, and von Sternberg while the highly stylized production design and cinematography of Way Down East (1920) suggested the visual majesty of Walsh, Ford, Wellman, and Borzage. As Griffith educated himself on the technology of the cinema he refined its language into the series of coded gestures that form the building blocks of visual media to this day.

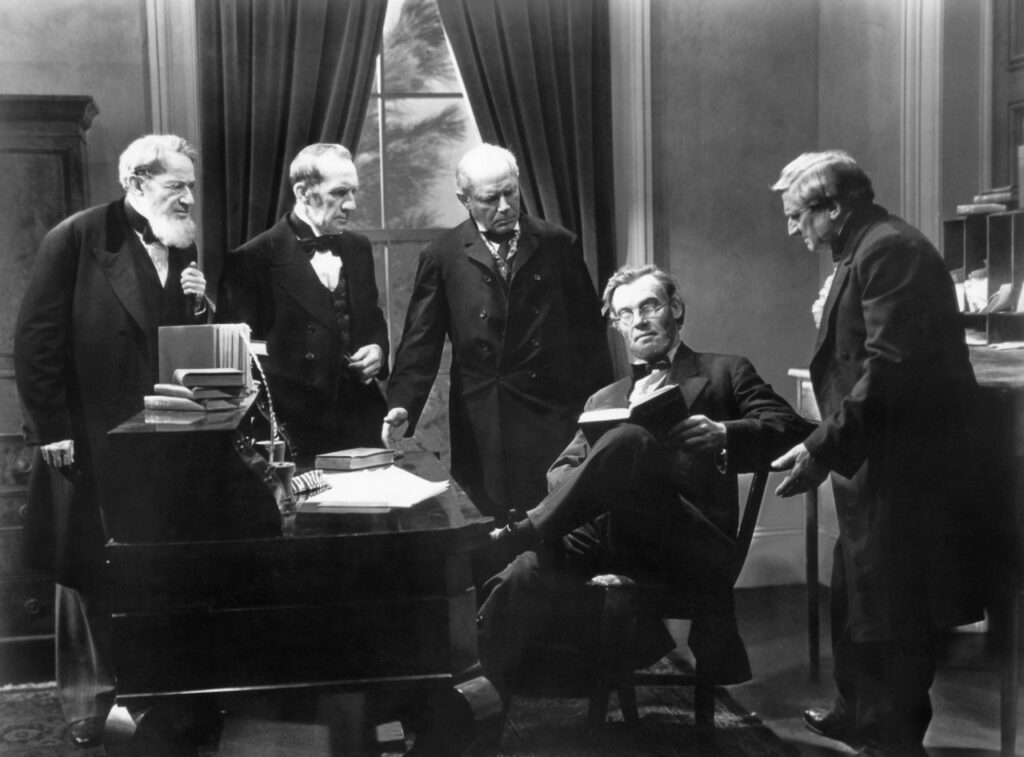

But with the advent of sound and the technical limitations that accompanied it Griffith adapted his style. In the winter of his career as a filmmaker Griffith became an essentialist. After completing over two-hundred films over the course of his career there was little for Griffith to prove. Thus, Abraham Lincoln is a film of bare essentials. Griffith does nothing overtly showy or operatic as he might have done in the 1910s, instead opting for a visual dialogue of a refined simplicity that mirrors the character of his subject.

Abraham Lincoln features two relatively brief battle sequences that re-create the same kinetic electricity of The Battle (1911) or The Birth Of The Nation with its sweeping crane shots. Abraham Lincoln utilizes some soundstage photography in the graveyard sequence and the shots of miniatures at the end which draw on the expressive imagery of Way Down East. But, even more sparingly, Abraham Lincoln utilizes the powerful close ups of Broken Blossoms as dramatic punctuations in those scenes of intense emotionality. In short, Griffith has distilled every aspect of his style to its most fundamental form to make Abraham Lincoln his most accessible and mature picture.

Griffith as a matured artist withdraws from the foreground and trusts his actors to imbue Abraham Lincoln with humanism. Griffith’s images are exact and record the actors in a perfect synthesis of the visual and the performative. Griffith trusts Walter Huston to animate the sixteenth president with emotional vitality and specific details while Griffith busies himself with a recording worthy of the performance. The result of this purest collaboration between actor and director is a film that presents a portrait of a flesh and blood human being in the idiom of late nineteenth century romanticism.

Be it the first or the tenth time that Huston mutters “we must preserve the Union”, it becomes clear that Abraham Lincoln is a film for the Great Depression. Themes of unity, equality, and national identity permeate every scene set in Washington. For Griffith the antidote to the problems plaguing the nation in 1931 can be found in President Lincoln’s unwavering devotion to the Union and the example of his noble bearing. Abraham Lincoln isn’t a film concerned with fidelity to the historic record, it is a film of myths and myth making.

However, it is apparent that Griffith does not seem himself in the character of the heroic president. Griffith is far too complex and self-aware to identify with an idealized figure who is, at least partly, of his own creation. Griffith is better reflected in General Robert E. Lee (Hobart Bosworth). Griffith, a southerner, was raised on the legend of the “Lost Cause” and many of his films reflect that unique and problematic world view. Lee, in the film Abraham Lincoln, is depicted as a figure of contradictions. On the one hand Lee is a vessel of war and Confederate values while on the other hand he is seen, in his one brief scene, as a compassionate man who values even the lives of the enemy. Lee in Abraham Lincoln is a reflection of Griffith’s relationship to the history of the Civil War that so many of his films attempt to deal with.

The curious thing about the relationship between General Lee the character in Abraham Lincoln and Griffith the filmmaker is that Griffith never intervenes. Griffith is content to slip this subtle bit of self-reflection into Abraham Lincoln without any fuss or gesture to apologize or justify himself. Griffith, who has outraged millions with The Birth Of A Nation quietly comes out as a hypocrite in one brief scene in a film about a man who had been much maligned in the earlier film. This vulnerable act of self-reflection may or may not have been a conscious decision for Griffith yet it remains one of the most pivotal moments in Abraham Lincoln.

Curiously, it is in the introduction to The Birth Of A Nation that was filmed on the set of Abraham Lincoln that the scene with General Lee finds its double. In this introduction to a decidedly anti-Lincoln picture, Griffith shows the camera and Walter Huston a medal his grandfather received as a Confederate soldier. Griffith celebrates his personal history with the legacy of the Confederacy with the man he has cast as Lincoln in an introduction to be screened before The Birth Of A Nation. The irony of these contradictions and their personal nature make this vignette the exaggerated echo of the more covert General Lee sequence in Abraham Lincoln.

Given the nature of the scene that has just been described it should come as no surprise that Abraham Lincoln does little more to address the institution of slavery in America than to include two harrowing scenes of violence. Emancipation, which was Lincoln’s greatest contribution to the U.S., is hardly even touched on in Abraham Lincoln. Griffith’s film is problematic to be sure but it isn’t without value to those interested in film history. To watch a film, or even enjoy it, does not necessarily mean that one endorses it.