“In art there is only artifice“-Luc Moullet

When one thinks of the American West one may recall the vistas of John Ford, prints by Mort Künstler, John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, the music of Ennio Morricone, or even perhaps Tom Mix, though that seems somewhat doubtful today. The West, with its legendary gunfighters, its promise of Western expansion, and the advent of railways that would unite the country have all worked together to solidify its myth in the consciousness of nearly every American. The West provides such a rich mythology that, within the cinema, it has become the single most American of film genres. It’s potential and versatility has even prompted filmmakers from without the United States to make films of the West. Just as American filmmakers embraced Arthurian legend and Roman history, so have the Europeans embraced the Western.

Luc Moullet remains one of the most neglected filmmakers of all time, and certainly of the French New Wave. Like Jacques Rivette, his films are near to impossible to obtain in the United States. All of this in spite of a significant critical re-evaluation by the likes of Jonathan Rosenbaum and others. Still, Luc Moullet’s A Girl Is A Gun (1971) is the most unique and thought-provoking film on this list.

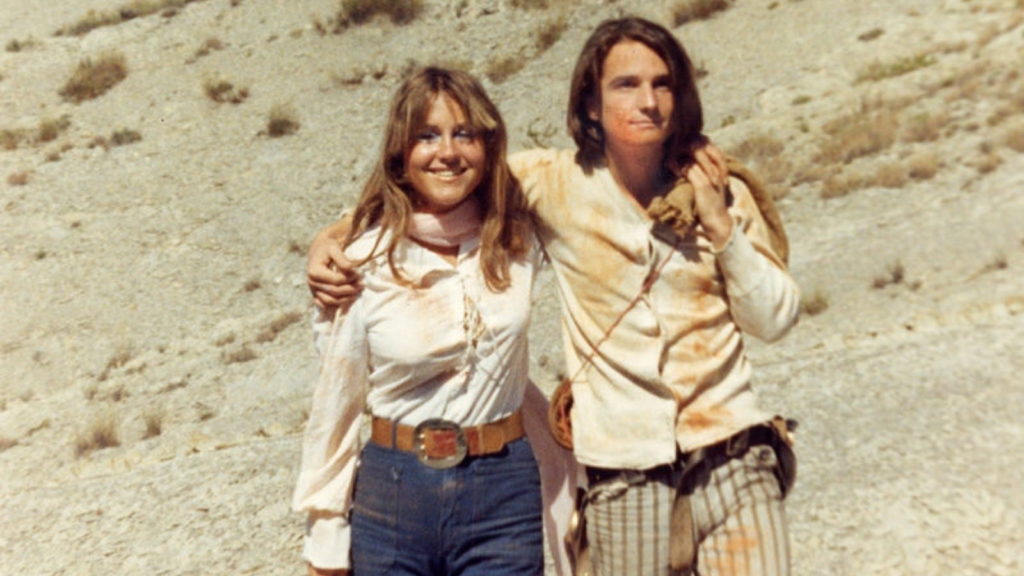

A Girl Is A Gun follows the misadventures of Jean-Pierre Léaud as Billy The Kid. Unlike most depictions of the famous gunslinger, Billy The Kid is depicted as a bumbling loser who, despite himself, manages to exact his revenge and steal the girlfriend of a man he has killed. The narrative content of A Girl Is A Gun is completely vacant of the Romanticism that unifies most American Westerns. Even Lonesome Cowboys plays into the popular Romantic notions of the Old West by being so totally dependent on the recognizable signifiers and tropes of the genre. Billy The Kid in Moullet’s film is, therefore, the antithesis of the genre itself.

That said, A Girl Is A Gun brings a bit of that Romanticism into play in terms of the films theme song and visual structure. But these mechanisms, in Moullet’s hands, work only to compliment and enhance the anti-Romanticism of the narrative. A Girl Is A Gun only superficially functions as a Western. As the film perverts the Romantic models it employs via the contrast of narrative content and technique, Moullet is able to disassemble and examine the Western Genre.

This deconstruction of the genre is playful, the precise opposite of the intellectualized genre deconstructions that Jean-Luc Godard became famous for in the sixties. This playfulness derives from A Girl Is A Gun‘s relatively low-budget, forcing Moulett to make a Western without either the vistas of Ford, the violence of Anthony Mann, nor the horses of every other Western. Moulett, like Warhol and Morrissey, is forced to make the film with the available resources, even if that restricts the films Western “look” to props and costume.

It must be said that this “superficiality of genre” in A Girl Is Gun comes from a unique place in the history of the genre. Where Sam Fuller may make a low-budget Western and accommodate that budget by distilling the narrative down to a hard-punching tale of revenge, Moullet decides instead to pay for devices such as a theme song with his budget. This decision on Moullet’s part places A Girl Is A Gun into the same category of “Western Camp” as Lonesome Cowboys, Rancho Notorious, Johnny Guitar, John Sturges’ Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (1957), and Douglas Sirk’s Taza-Son Of Cochise (1954). Critics like Jonas Mekas would interpret this alignment of stylistic concerns with Pop Art, which seems to be what A Girl Is A Gun is getting at.

Luc Moullet obviously does not have a strong Romantic connection with the Western genre. For him it is a unique spectacle in that it is a legitimate genre. A Girl Is A Gun is a testament to Moullet’s view of the cinema as entertainment first and foremost.