Todd Haynes has tried his hand at a variety of styles and narrative approaches. From Poison (1991) to I’m Not There (2007) his cinematic style has proven to be as versatile and as challenging as any filmmaker working in America today. In 2011 he tackled the melodrama head-on in a six-hour miniseries for HBO, Mildred Pierce. Borrowing heavily from the cinemas of Douglas Sirk and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, as he did with Far From Heaven (2002) and later in Carol (2015), Haynes invigorates the genre by implementing the old and tried conventions within the context of a sprawling, character driven narrative.

First, I would like to point out how far HBO has allowed the television miniseries to come since its conception. HBO encourages established and decidedly cinematic filmmakers to create what are essentially epic films that need not be inhibited by running time. The funny thing is, such an approach has been the standard in Europe since the early seventies. Why it took so long to catch on in the U.S. I do not know.

Working with this medium of epic story telling, Haynes and his co-writer Jon Raymond have crafted a script that remains much more faithful to James M. Cain’s masterful novel than Michael Curtiz’s film. Utilizing the scope of the miniseries, they have crafted a film that progresses at a slow pace, allowing performance to exist at the forefront of the film. Here, at the center of the film is Kate Winslet in the title role. She doesn’t play Mildred as a “type” for sympathy, preferring instead an organically objective approach that show cases both the good and the bad in her character with a visceral sense of the everyday, the mundane. Evan Rachel Wood plays her daughter Veda, a spoiled and sociopathic upstart who serves as the catalyst for nearly every evil that befalls Mildred. Guy Pearce plays Mildred’s second husband Monty, a charming opportunist and rake. In the narrative, it is Veda and Monty who present the obstacles and betrayals which prevent Mildred from enjoying that which she has achieved (when her first husband leaves her, she starts a chain of restaurants).

Cain’s novel has all the trappings of classic Hollywood melodrama, and Haynes doesn’t shy away from incorporating old Hollywood styles into the film to reflect that. Still, Haynes doesn’t cut his shots to maximize narrative exposition. The shots in Mildred Pierce linger, inviting the spectator into the world of the film, impressing upon us the smallest details of the lives of the characters.

Like Douglas Sirk, Haynes often frames his characters reflected in mirrors or seen through a window or some sort of glass. As Sirk once did, Haynes carefully picks his shots in which he wishes to distort the audience’s view of the character. Haynes also permits his actors to play their parts a little too “big” at times, pushing for a Wagnerian effect right out of the “weepies” of the 1930s and 1940s as much as for Brechtian impact. The mood of these “big” moments, given their duration and the exaggerated posturing of the actors, at times feels less like Sirk and more like Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s interpretation of Sirk. Perhaps that is because, unlike Sirk, Fassbinder’s work made allowances for depictions of womanhood that were not predicated on the tastes of a Hollywood studio.

But Haynes does more than just imitate style and convention. Mildred Pierce is a decidedly Todd Haynes film. His obsession with sexual subversion is ever present and factors heavily into the lives of the film’s characters. Even before Mildred discovers Eva’s affair with Monty, sex is used to manipulate and undermine different characters. Monty is essentially Mildred’s gigolo after all. The complex that exists in Mildred Pierce, in terms of sex and power, is derived cinematographically from Fassbinder’s dramas post-The Merchant Of Four Seasons (1971). In combining Fassbinder’s strategies for “power-plays” within a narrative with Cain’s original novel Haynes is able to reincorporate the aesthetic of the classic melodrama into the contemporary character study as well as into the stylistic vernacular of the episodic television drama.

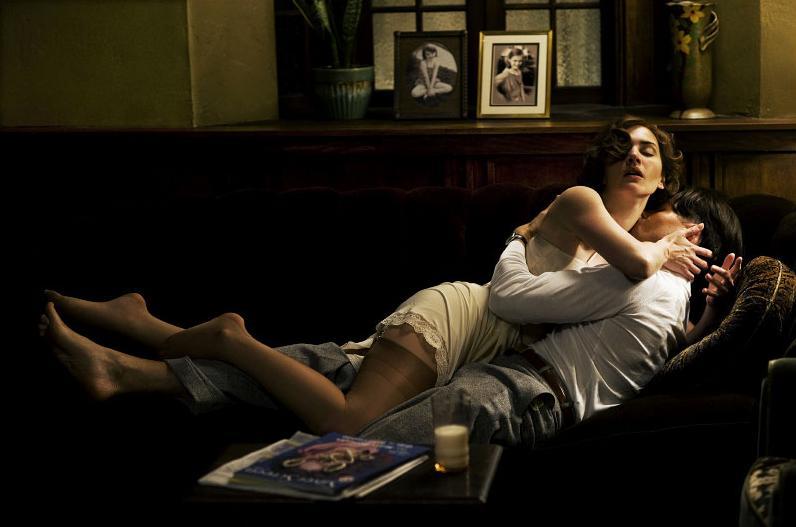

Consider now the level of grief and shame Haynes gets from Winslet when she confronts Veda about faking her pregnancy to black mail a film director’s son. Winslet’s face twists and bursts with tears. In the hands of another director, moments such as these would not be played quite so over the top for quite so long. In a scene where Mildred catches Veda in bed with Monty, there is a long 18 second shot of Veda naked, combing her hair after sex. Haynes then cuts back to Mildred as her face slowly reveals her emotional pain. The audience doesn’t need to see the sex act. The perverse nature of the sex is clear enough in this juxtaposition of these shots that it would have been less effective to show it.