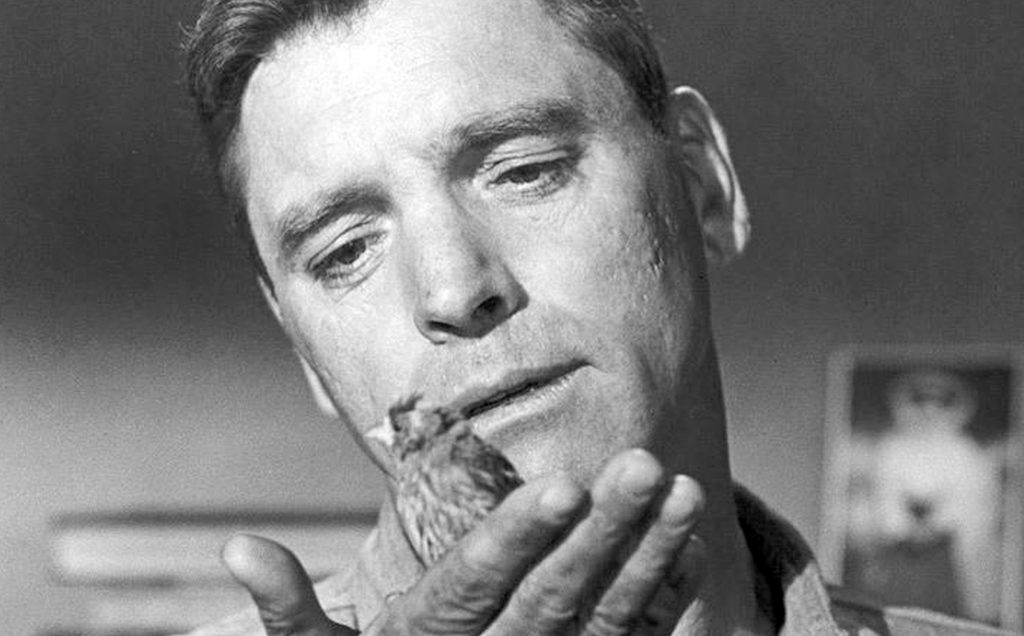

Of the films John Frankenheimer directed Burt Lancaster in, Birdman Of Alcatraz (1962) is perhaps the one that displays the full array of Burt Lancaster’s scope as an actor. The only other film that comes close from their decade long collaboration is The Gypsy Moths (1969), where Lancaster is cast against type and utilized much in the same way as Luchino Visconti employed the matinée idol in The Leopard (1963) and Conversation Piece (1974). But there are also a number of technical merits to The Birdman Of Alcatraz, Frankenheimer’s fourth feature, that have maintained the films reputation as a remarkable cinematic achievement in the twilight of the studio era.

Guy Trosper’s screenplay adaptation of the book by Thomas Gaddis lends itself well to Frankenheimer’s style. Frankenheimer’s films are direct, methodically paced ruminations on human character, particularly instances when character is put to the test by outside political forces. This social conscious in both Frankenheimer’s directorial approach and Trosper’s writing beg comparisons to the “social action” films of Sam Fuller. Unlike Fuller, Frankenheimer’s direction avoids any direct confrontation with either genre or audience expectations. Frankenheimer’s subversions in this realm are restricted to the casting of and direction of his actors’ performances. Consider the tone and pace of Birdman Of Alcatraz compared to Richard Brooks’ Elmer Gantry (196). Both films feature Burt Lancaster in what is ostensibly a character study. Elmer Gantry is a fast paced, raucous, and over the top film while Birdman Of Alcatraz veers more in the direction of realism.

What’s also compelling about what Trosper brought to the project is Edmond O’Brien’s voice over as the author Gaddis himself. This voice over accomplishes two things. Firstly it signifies a reliable source of information about the Lancaster character Robert Stroud that, until the film’s conclusion, has no face to it on-screen. This tactic represents the illusion of objectivity and thus a clearer relationship to our shared reality as opposed to a subjective interpretation where, as in The Shawshank Redemption (1994), the perspective is subjective to that of an on-screen character and thus a world apart from our shared reality as an audience. Secondly, the voice over provides a degree of self-awareness by simply being a fantastic device, working along Brechtian parameters to keep the audience at arm’s length from a subject (the American penal system) that, more often than not, makes an audience uncomfortable. The antithesis to this being well represented by Alan Clarke’s television version of Scum (1977), which some accounts claim was seen as so realistic that it was mistaken by viewers as being a documentary.

Visually, Birdman of Alcatraz may be the best film about solitude within the penal system ever produced by a major studio up until that point. In high contrast black and white photography, Frankenheimer and cinematographer Burnett Gufey construct compositions where light is a microcosmic invading force, emoting the loss, desperation, and despair of the physical space referred to as “solitary confinement”. The best example of this occurs when the food slot is opened in Lancaster’s cell door and the guard slides a plate of food through the slot. A burst of light in the shape of an elongated rectangle cuts across the floor, barely illuminating Lancaster. This stark approach, while not derivative of either German Expressionism nor Film Noir (primarily because this choice does not reflect the subjective reading of physical space by Stroud), recalls an earlier Lancaster film directed by Jules Dassin, Brute Force (1947).

As a whole, these various elements come together under Frankenheimer’s direction as a sort of odyssey through the gradual psychological metamorphisis of Robert Stroud. These elements are reigned in by Frankenheimer to contain, and at times compliment, Lancaster’s performance. The effect is subtle in the immediate experience of viewing Birdman Of Alcatraz, but quite dynamic in retrospect. In just a little over two hours one sees Burt Lancaster’s Robert Stroud transform from a violent convict into a pacifist intellectual. Though this crude summation may give the impression that Frankenheimer’s film advocates incarceration it must be firmly stated that it does not. Repeatedly throughout the film one observes Stroud’s reformation and the various catalysts for this change. And in every instance it is the penal system that impedes these changes. If one were to compare the narrative trajectory of Robert Stroud in Birdman Of Alcatraz to the career of its director John Frankenheimer, one might suppose that, for Frankenheimer, the penal system is a kind of metaphor for the major studios in which he worked.