Norman Mailer’s best novel is The Executioner’s Song. The author, whose voice can overpower his work, is almost entirely absent. The novel reads almost as a list of facts and casual observations of specific details. In 1982 Mailer adapted The Executioner’s Song into a screenplay for Lawrence Schiller to direct as a two-part television film. Schiller had done all of the research for the novel and remains remarkably faithful to its minimalist style. The films’ two parts reflect the two books within the novel, the protagonist changing between the two.

When Mailer adapted his novel Tough Guys Don’t Dance for himself to direct for Canon Films he had chosen that novel deliberately, because it was bad. For Mailer the medium of film became a way to “fix” his novel, to open it up and give it qualities he couldn’t render on the page. The film and book reimagine the typical film noir as a psychosexual mid-life crisis of bizarre, otherworldly gestures and postures, born out of a fatalistic mania and self destructive impulse.

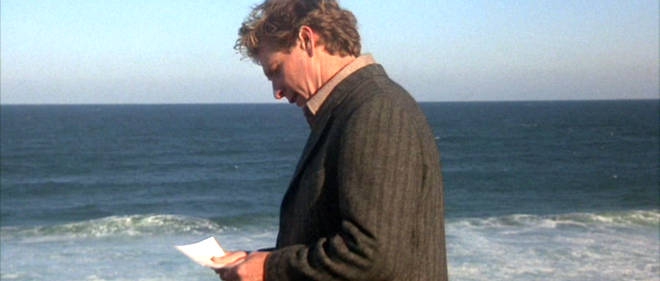

No one could have directed Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987) the way Norman Mailer did. It’s evident in his earlier underground films of the late sixties that Mailer saw film as a collaborative and communal exercise in whose space a novel literally comes to life. In Tough Guys Don’t Dance, with the rigors in place of a typical Hollywood production, Mailer’s style takes on a kind of dementia. Dialogue is delivered as a series of dramatic proclamations, foregoing any resemblance to any real conversation. The gestures of the characters are wooden as if the cast had undergone some kind of hypnosis. Ryan O’Neal, Wings Hauser and Isabella Rossellini all come off as totally unhinged and damaged individuals.

Of course this is the point of Tough Guys Don’t Dance. If the characters in Out Of The Past (1947) were somehow transposed into our reality wouldn’t they also seem deranged and ghoulish? The restraint of The Executioner’s Song actually does remain, holding back on the film noir impulses within the realm of the visuals in Tough Guys Don’t Dance. In fact Mailer seems to have shot the film as if it were the movie of the week on some public television station in the eighties. What is unrestrained in the film are the performances.

Mailer’s bold direction and unorthodox choices of style have kept Tough Guys Don’t Dance a well hidden masterpiece. One has to wonder if Jean-Luc Godard influenced Mailer in anyway since they had previously collaborated on an adaptation of King Lear. Godard’s experimental approach to post-modernism could have easily included Tough Guys Don’t Dance in his oeuvre. However, that isn’t to say that Tough Guys Don’t Dance isn’t a distinctly Norman Mailer production. As I said earlier, no one could have made Tough Guys Don’t Dance the way that Norman Mailer did. Mailer’s machismo, his chauvinism, his bluster, and his egotism are all on display here.

Yet, if Ryan O’Neal’s character is the typical Mailer protagonist then Tough Guys Don’t Dance is an exercise in character assassination. Here Mailer undermines his tough guy characters like Randy D.J. Jethroe, Stephen Rojack and Tim Madden, exposing their macho posturing for what it truly is. Mailer pulls back the curtain on himself and is utterly disgusted by what is laid to bare. Perhaps that’s why Mailer applied his signature brand of self-promotion to the trailers for Tough Guys Don’t Dance. Alone, Mailer reads the negative audience test cards from preview screenings of the film directly into the camera. It’s a kind of joke, but it’s a joke Mailer is playing on himself.