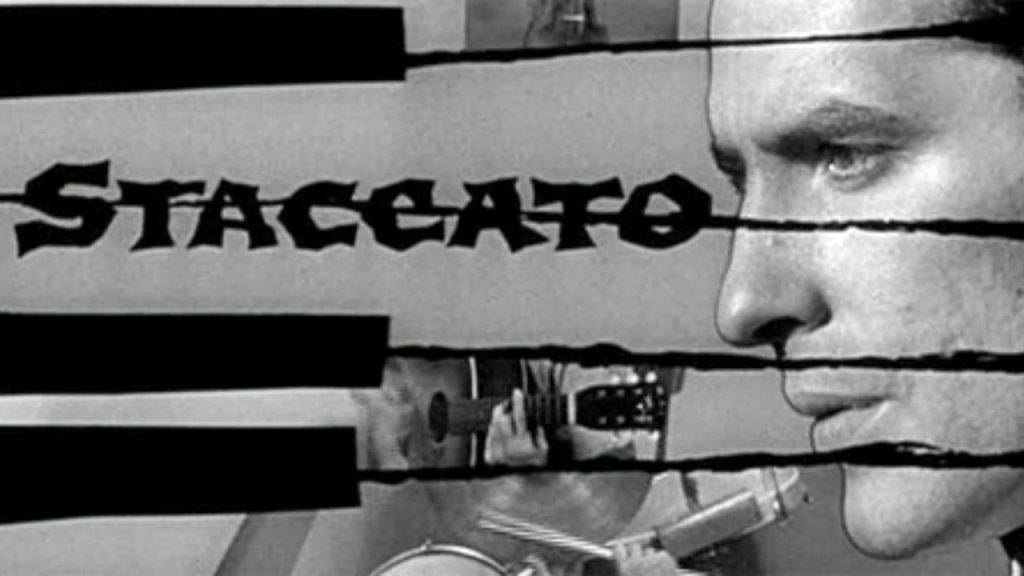

If you are like me and you enjoy Frank Kane’s or Howard Norman’s gumshoe novels then you’ll probably get into Johnny Staccato. Otherwise, Johnny Staccato is pretty unremarkable as a television show. It bares all the hallmarks of its moment, good and bad. But as a document of filmmaker John Cassavetes’ earliest outings as a director, Johnny Staccato is an essential document.

Strangely, film critics and historians often overlook Johnny Staccato in their studies of Cassavetes, bypassing the five episodes he directed of the show and moving from Shadows (1958) straight to Too Late Blues (1961). Even Ray Carney dedicates only three pages in his Cassavetes on Cassavetes (the definitive text on the filmmaker) to Johnny Staccato. So why this oversight? Perhaps it is because Cassavetes himself didn’t much care for his work on the show. Or, even more likely, this neglect could be the byproduct of the antiquated notion that television is inferior to the cinema (a distinction most audiences under the age of sixty no longer make).

Of the 27 episodes that make up the entirety of Johnny Staccato only five were directed by John Cassavetes (collectively that is roughly a 100 minute runtime, the average for a feature film in 1959). And, just as one would assume, these episodes (Murder For Credit, Evil, A Piece Of Paradise, Night of Jeopardy, and Solomon) have little in common with the aesthetic principles at work in Shadows. But they don’t have that much in common with Too Late Blues or A Child is Waiting (1963) either.

The Cassavetes style of directing the viewer’s gaze to subtle nuances within character interactions through a quick succession of cuts, camera moves, etc. doesn’t exist on an obvious level in Johnny Staccato. On Staccato Cassavetes prefers longer wide shots that ground the characters in their setting, physically and politically. In his later films this interest in character and space is just as important (consider Cosmo of Killing Of A Chinese Bookie and his relationship to his club as an obvious example), though by the seventies Cassavetes is much more overtly interested in how characters navigate one another’s spaces. Still, one can see this idea begin to form in Johnny Staccato. By shooting wide Cassavetes directs our gaze to the space rather than the individual, making the journey through space by the character of a far more singularly immediate importance.

That said, Cassavetes’ work on Johnny Staccato takes an approach that is much more theatrical than that of his films. Every interest, such as the one discussed above, is isolated within a complex of single cinematic gestures. By comparison, the use of the camera and of montage in his films from Faces (1968) onwards indicates an overlapping or a multitasking of aesthetic strategies. Even in Too Late Blues and A Child Is Waiting Cassavetes has matured enough to dispense with the notion of one “meaning” per shot.

Within the context of his filmography Johnny Staccato is very much the antithesis of Shadows. Shadows served its performers and their characters exclusively while Staccato, which is much more formally rigid, serves its 20 minute narrative before its characters. In a manner of speaking, if one were to combine the free spirited nature of Shadows with the more formally concerned Staccato one could very well end up with a film like A Woman Under The Influence (1974).