I first encountered Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls at a friend’s house in high school (probably between 2005 and 2007). We had just finished swimming and were relaxing poolside when he picked up a copy of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls from a table and proceeded to show me the parts detailing Francis Coppola’s worst moments as a human being. It feels like gossip reporting, but I guess that’s the point. Biskind offers his readers something human about the otherworldly celebrities whose lives he reports. The fact that he has been able to remain so objective over the course of his long career is a marvel unto itself.

Biskind’s first book, published in 1983, Seeing Is Believing follows the course of popular American filmmaking in the fifties. Biskind singles out a dozen film titles that he then gives a brief production history of and some mild mannered criticism. The book maintains a casual tone throughout, but what makes the read truly intriguing is how the book soon becomes a portrait of its author. Biskind’s mild mannered criticism is just that, amateurish film analysis whose primary concern is the historical context of the film. However, Biskind’s own nostalgia for most of the films is at conflict with the context he forces himself to place the titles in. A worthwhile example of this would be his piece on Fred Zinnemann’s film From Here To Eternity. Stylistically speaking, the most important aspect of Biskind’s first book is how well he draws illuminating parallels between the moviemakers and the movies they made.

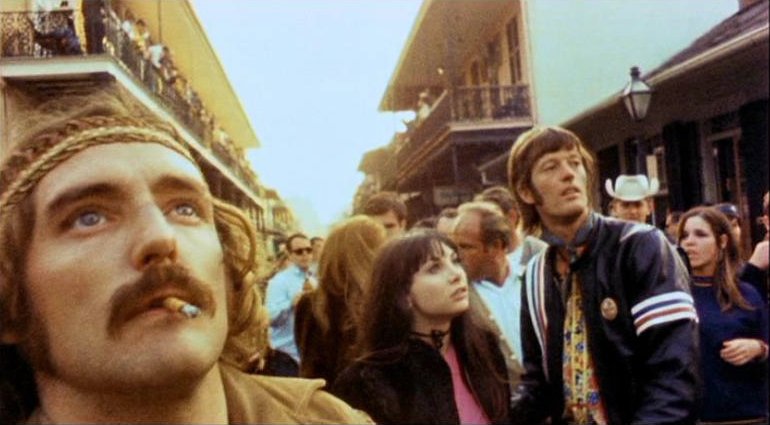

This talent is what makes his book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998) his masterpiece. Most readers go digging for stories about Robert Towne’s dog, Francis Coppola dropping his pants, Peter Bogdanovich’s sexual triumphs, William Friedkin sadistically torturing Ellen Burstyn, and of course everything having to do with BBS or Roman Polanski. The book focuses on Hollywood from the rise of Warren Beatty’s producer power on the production of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde to the death of Hal Ashby. It seems likely that the book sold so well based exclusively on the strength of its Hollywood Babylon-esque gossip.

To dismiss Easy Riders, Raging Bulls as an anthology of 1970s Hollywood gossip would negate the most compelling component of Biskind’s writing. Let me make use of the most obvious example; Roman Polanski. Biskind can find Polanski’s personal grief, obsessions and paranoia manifesting themselves not just on the screen, but also during film production. Thus, Biskind provides an accurate portrait of Polanski the film artist. Amazingly, Biskind accomplishes what he did with Polanski with almost all of his subjects, and he is even able to tie all their stories together cohesively (one is maybe tempted to say Easy Riders, Raging Bulls is to Hollywood what Robert Altman’s film Nashville was to Nashville).

What works better in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls is that Biskind does not attempt the analysis of these films as he did in Seeing Is Believing. It succeeds better as factual reporting, allowing contexts and connections to slowly and organically reveal themselves to the reader, who can then quite easily make applications to the films discussed in the book as an active audience member. It cannot be stressed enough how important the history and lives of filmmakers are to understanding the films they have created.